American mom fights for children to share her birthright

Published 7:00 am Sunday, May 29, 2011

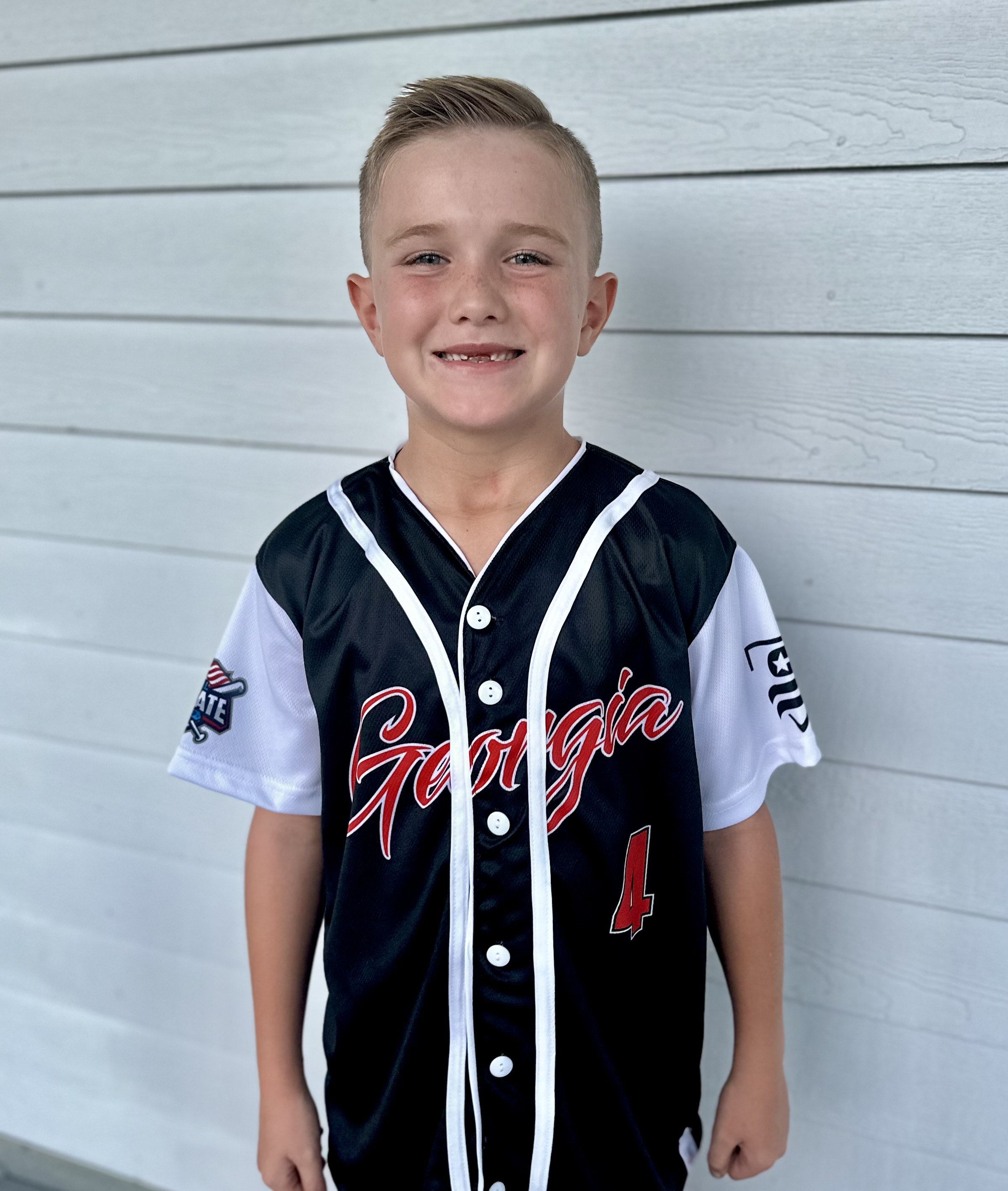

- Graeme and Scarlet Treloar of Valdosta pose with children (clockwise) Emily, Taylor, Jonathan, Joshua, and Kylie at the couple’s church and place of employment, Azalea City Church of God. The Treloar children were born in Australia to American-citizen mom Scarlet, but their U.S. citizenship has been denied.

As an American citizen having children in Australia, Scarlet Treloar thought her five children were also American citizens.

Trending

Coming home proved her assumption wrong.

Though the family has lived in the United States and Valdosta since 1996, the Treloars have faced an uphill battle to make their children a part of the American Dream.

Oldest daughter Kylie, 25, was 11 when she arrived in America. She cannot get a green card. She cannot get a driver’s license. Without photo identification, she cannot enroll in college. Without a Social Security card, she cannot get a job. She lives with the family, babysits, cleans houses and has worked in fields.

Daughter Emily, 24, was 9 when she arrived in America. She is married to a Marine veteran who served in Iraq. She married for love, not citizenship. She is in the same situation as Kylie in terms of residency. Emily has a toddler daughter who is an American citizen with a Social Security number. She has a second child on the way.

Oldest son Joshua, 22, and youngest son Taylor, 18, were respectively 8 and 4 when the Treloars arrived in the U.S. They have been granted the proper paperwork allowing them to get driver’s licenses, work, attend college. Joshua is seeking employment. Taylor, who speaks fluent Spanish, plans to become a Spanish teacher.

Middle son and fourth child Jonathan, 20, is the Treloar facing the most difficult straits. Like his sisters, he does not have the paperwork allowing him to officially seek employment, to drive, or attend college. Though he has lived in Valdosta since the age of 6, Jonathan has received paperwork that he is being considered for deportation back to Australia, a move that would tear this tight-knit church family apart.

Trending

The Treloars have never asked for help in their 14-year battle with the federal Immigration & Naturalization Services. But with the threat of Jonathan’s deportation, the Treloars have begun speaking publicly about their struggles.

“All I’ve been asking for years is the right as an American citizen for my children to have their rights to live and work here,” Scarlet Treloar says.

Scarlet grew up in Valdosta, the daughter of missionaries W.H. and Marie McLeod. At the age of 15, Scarlet moved with her parents to a missionary assignment in Australia. They arrived in Australia on May 1, 1981. On June 28, 1981, Scarlet turned 16. She didn’t know it then but that nearly two-month delay in turning 16 in Australia would have serious consequences on her future family.

As a 16-year-old, Scarlet met and fell in love with Graeme Treloar, a native Australian. Scarlet was 17 when she married Graeme.

They continued living and working in Australia. They had children. As an American citizen, Scarlet was curious about the citizenship of her children. The American consulate assured her the children retained American citizenship. Scarlet assumed her children had something akin to a dual citizenship as both Americans and Australians.

In the mid-1990s, 16 years after Scarlet arrived as the daughter of American missionaries, she, Graeme and their five young children moved to the United States. They wanted a better life. They wanted better education opportunities for their children.

They returned to Scarlet’s hometown of Valdosta. Graeme received permanent residence status. To their surprise, the children’s status remained uncertain. It became apparent when Kylie attempted to get her driver’s license and was denied.

To Scarlet and Graeme’s shock, the children weren’t automatically considered American citizens. As they understand it, the children’s status rested on a loophole regarding Scarlet’s age at the time of her arrival in Australia. Had she been 16 or older upon her arrival, her children would have automatically been regarded as U.S. citizens. Since she was not 16 at the time of her arrival, her children had no automatic guarantees as Americans.

So, their battles with INS began. Given their oldest child was 11 and their youngest 4 in 1996, they never imagined they would still be struggling with immigration when their children reached adulthood.

Through the years, all seven Treloars have traveled as a family countless times to Atlanta. They would follow one INS representative’s instructions exactly only to have another bureaucrat tell the family that they had done something or everything wrong.

Some forms cost hundreds of dollars to file. Multiply that amount by five then multiply it again due to bureaucratic errors. Top those amounts with the purchase of gas to travel back and forth along with lodgings in Atlanta for a family of seven. The Treloars have never sought government assistance. They have never applied for or used food stamps, for example. Still, the bureaucratic battle has placed an economic strain on the family.

Graeme is the missions outlook pastor at Azalea City Church of God on St. Augustine Road. Scarlet is the church’s administrative secretary.

Graeme faces two ironies in his job. He works with South Georgia’s Hispanic community. His INS struggles have given him insight into many Hispanic families’ plights. He also coordinates international mission trips, travels his children cannot make lest they are denied return to the U.S.

After all, it was a return trip to Australia that has led to Jonathan facing the possibility of deportation.

Several months ago, Graeme’s father became ill in Australia. The illness was serious. Jonathan wished to see his grandfather and knew his grandmother would need help. Jonathan went to Australia. There, his grandfather died. Graeme returned to Australia to bury his father and help his mother adjust.

Before the trip, Jonathan’s immigration status had been on a path similar to his brothers’ cases. While Joshua and Taylor received residency status, Jonathan received the letter that he had been entered into the deportation process.

The Treloars began contacting congressional representatives and news media. Something they had never done regarding their immigration battles. They told Rep. Jack Kingston’s office about their case, specifically the threat of Jonathan’s deportation. While Kingston’s office cannot comment on the progress of such cases, the Treloars have since received a letter that Jonathan’s status for possible deportation will be reviewed. This review is not a guarantee, but it is a reprieve. The Treloars can keep fighting for Jonathan to stay in the United States. They have been asked to prove the importance of having Jonathan stay close to the family.

“How do you ask a mother to explain the importance of not seeing one of her children taken away?” Scarlet explains. “They want us to explain what Jonathan means to his family.”

The Treloars have kept their wits in these struggles by keeping and honing a fine sense of humor. Throughout the session with the entire family, sons Joshua and Jonathan maintain a running banter of jokes. The family laughs often amongst themselves. Though she doesn’t say it exactly, Scarlet seems to live by the old adage of laugh to keep from crying.

Given their experiences, the Treloars also have a sharpened view of the American immigration system. Pundits and many others can complain that U.S. immigration policy has problems. The Treloars have lived those convoluted and vague problems.

Scarlet would like to think of American immigration as the ideal engraved on the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free …” Especially given her American citizenship and the belief that her children should be the rightful heirs to that citizenship. But their experiences have tainted how they view the symbols of liberty and the idea of the American Dream.

Had he known what his family would endure, how his children’s freedoms have been curtailed, Graeme says the Treloars would have stayed in Australia.

Scarlet says she has often thought of returning to Australia.

“If I could pack my church up, my family and friends and take them to Australia with me, we would go,” Scarlet Treloar says, emotion quivering at her lips. “I’m an American, but this is not the America I was raised in.”