Why do so many ESPN personalities get suspended?

Published 10:48 am Saturday, April 18, 2015

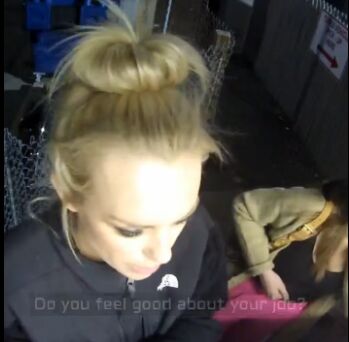

- Britt McHenry

ESPN, the self-styled “Worldwide Leader” in sports broadcasting, may also lead the news media in another category: the number of employees suspended or fired for doing or saying something boneheaded.

The cable network has a long and storied history of sending its reporters, hosts and producers to the sidelines after embarrassing episodes that grabbed headlines. The list includes some of ESPN’s best-known personalities, including Bill Simmons, Dan Le Batard, Stephen A. Smith and Keith Olbermann. And that’s just in the past year or so.

At ESPN, you apparently haven’t arrived until your boss tells you to stay home.

On Thursday, the Disney-owned network rung up another: reporter Britt McHenry, who got a week in the penalty box after a security-cam video caught her abusing a cashier at an Arlington, Virginia, tow-truck compound. McHenry, a former sportscaster at WJLA (Channel 7) in Washington, lost her cool after her car was towed from a parking lot. “Lose some weight, baby girl,” was one of the kinder things McHenry said to the employee on the video, which drew a wave of social-media outrage when it leaked onto the Internet.

Prominent ESPN employees have been zapped for all manner of transgressions: racist comments, misogynist comments, comments about gays and Hitler, office affairs, sexual harassment, or just for being a jerk. Olbermann, the much-traveled sports and news commentator, went down for a week during February for writing insulting things to Penn State students on Twitter. Former Washington Post columnist-turned-ESPN-star Tony Kornheiser got two weeks in the cooler for criticizing fellow host Hannah Storm’s wardrobe on his radio show in 2010. (Kornheiser and Olbermann are both two-time losers; they were also suspended in 2002 and 1997, respectively.)

During one two-week stretch last summer, ESPN hit the trifecta, suspending three of its hosts for unrelated infractions. The most notorious of these was the suspension of Smith, who suggested during the Ray Rice debacle that women sometimes invite domestic violence by “provoking” men into beating them up.

The network’s dishonor roll is so long, stretching to more than two dozen names, that it raises the obvious question: Why does this happen so often at ESPN but not at, say, PBS? Is it something in the air around ESPN’s headquarters in Bristol, Connecticut?

Maybe.

“There’s an amplified environment” at ESPN, much like that around highly competitive athletes, said James Andrew Miller, the co-author (with former Washington Post critic Tom Shales) of “These Guys Have All the Fun: Inside the World of ESPN,” published in 2011. “People who are on the air get riled up, and they earn their money by being provocative and saying provocative things and getting into debates. That’s in the DNA of their job description and their brand.”

Sometimes the testosterone surge isn’t just confined to the studio. Miller recalls conducting an interview for his book with an ESPN personality, whom he wouldn’t identify, as the man ordered lunch at a drive-through restaurant. After a brief exchange with the order taker, the man became enraged. “He went to Defcon 1 on the burger person,” Miller said. “I was just horrified.”

Concludes Miller: “It takes unbelievable dexterity to be a certain way on the air, and when a producer yells ‘Nice show’ at the end, to walk off the set and not show any signs of that personality. That’s a judo move even Olivier couldn’t pull off.”

ESPN suggests its suspension rate isn’t especially high, at least relative to the number of people it employs to sling opinions on TV, radio, online and in print. Further, when it does take action, it says its high profile draws disproportionate attention. “We have approximately 1,200 commentators, working for a highly visible company that is aggressively covered on a daily basis,” spokesman Josh Krulewitz said.

One curious aspect of ESPN’s many suspensions are the penalties it hands out. While not all infractions are created equal, the duration of the suspensions is all over the field. Some have lasted two days; others were for a week. Still others went multiple weeks, despite the infraction being similar to another that earned a lesser penalty.

Simmons, for example, was ordered to sit out for three weeks in September when he said on a podcast that NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell was “a liar” for his statements about the Rice incident. But Smith got just one week for comments that many – including a fellow ESPN personality, Michelle Beadle – said insulted women. Kornheiser got two weeks for criticizing Storm, while anchor Max Bretos got 30 days off in 2012 for uttering a racial slur on the air about former New York Knicks star Jeremy Lin.

Said Krulewitz: “If and when a mistake is made, our goal in each individual situation is to determine a fair and appropriate reaction, even if that may result in additional public attention.”

But Miller lays out the criteria this way: “When you go after one of ESPN’s business partners [such as the NFL], the stakes obviously get higher. And when you go after a fellow employee, that’s another third rail. They don’t want civil wars breaking out at the office.”

ESPN has fired people, too, but it’s hard to discern exactly what rates the death penalty and what doesn’t at the network.

Baseball analyst Harold Reynolds lost his job 2006 for alleged sexual harassment. But announcer Mike Tirico got a three-month suspension in the 1990s for much the same behavior, according to “ESPN: The Uncensored History” by sportswriter Michael Freeman. And at least three others, including analyst Steve Phillips, were canned when their affairs with fellow employees became public.

But sometimes just using the wrong words is enough. An unidentified Web producer was let go in 2012 for employing the same slur about Lin in a headline that earned Bretos a 30-day suspension. Meanwhile, ESPN fired veteran play-by-play man Ron Franklin in 2011 for calling a female colleague “sweet baby” during an off-air meeting and insulting her further after she objected.