Remembering Gypsy : A look back at Valdosta’s 1902 elephant rampage

Published 5:00 am Sunday, July 26, 2015

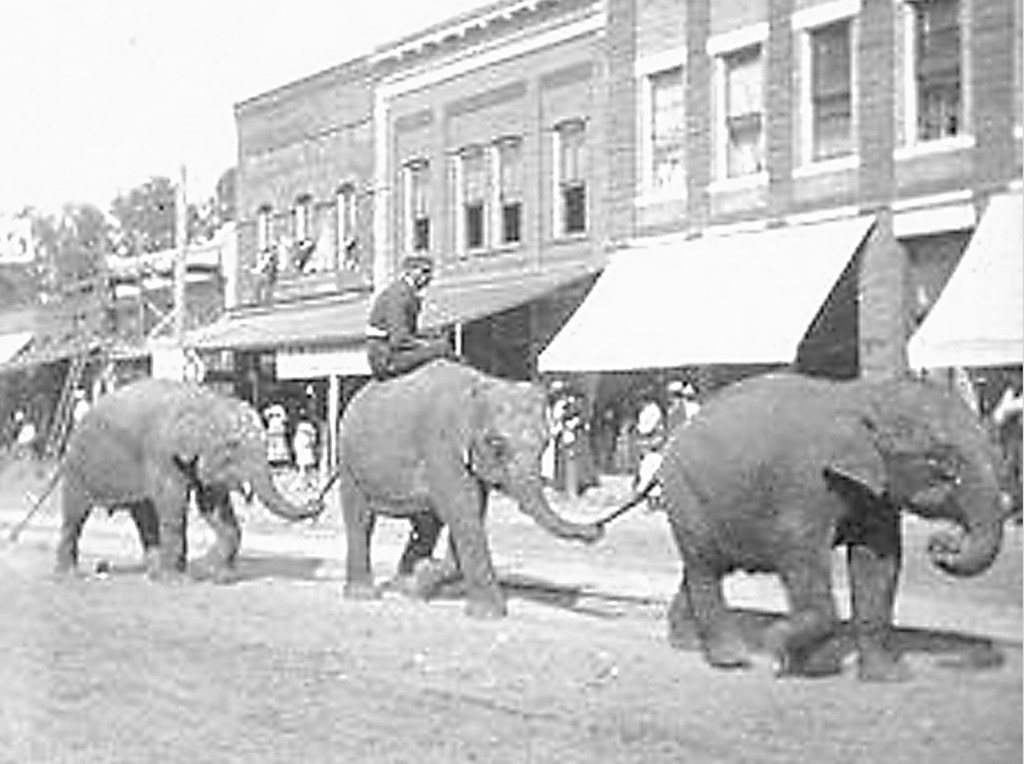

- One of the elephants in this undated photograph is believed to be Gypsy.

Lowndes County Historical Society Museum is filled with the richness of Valdosta’s history, from the days of King Cotton and a downtown trolley-car system to the arrival of Moody Air Field and the growth of Valdosta State. Yet, one tale of old Valdosta typically garners more curiosity and questions from museum staff than any other.

Though more than a century old, many children want to know more about Gypsy, the traveling circus elephant that murdered her trainer and ran amok for a full night through the streets of Valdosta before she was shot and killed.

Indeed, the story of Gypsy the elephant has fascinated Valdosta children and adults for generations.

Often, within weeks of a newcomer’s arrival to Valdosta, a long-time resident shares the tale of the rampaging elephant. Oddly this behavior was predicted, as The Valdosta Times Editor C.C. Brantley noted in 1902.

“Generations unborn,” Brantley wrote, “will be told about things that happened the day the mad elephant was killed near Valdosta.”

Valdosta was not the location of the first violent day in Gypsy’s life, but it was her last.

She reportedly killed other trainers and circus employees prior to killing trainer James “Whiskey Red” O’Rourke in Valdosta.

A Deadly Reputation

“Tough Circus Elephants,” a 1993 article by Bill Johnston, documented the lives of several rogue circus elephants, including the Asian elephant Gypsy, referred to as “one of the toughest elephants ever imported to this country.”

Circus man John “Pogey” O’Brien imported Gypsy in 1867 to the United States. In 1888, she was sold to the Clark Bros. Shows. In 1891, Gypsy was sold to W.H. Harris Nickel Plate Shows.

“Gypsy had killed four men by then. Elephant men carved notches on her tusks as a record of her victims,” Johnston wrote. “ … Gypsy had never bothered women or children, but apparently only went after people connected with the show.”

In Ronceford, Va., a circus employee awoke with a chill in the middle of a cold night. To warm his tent bed, he took some hay from Gypsy and returned to sleep under the big top’s canvas with four other tent men.

“It was a fatal mistake,” Johnston wrote. “Gypsy broke loose from her chains and snatched the hay thief … then slammed him into the ground, killing him instantly.”

Her revenge complete, Gypsy calmly allowed trainer Bernard Shea to chain her again.

In 1896, during a Chicago show, Shea was away and animal handler Frank Scott ignored warnings to leave Gypsy alone. He exercised her. Scott climbed onto Gypsy’s back and sat on her head, the usual custom for riding an elephant.

Riding down an alley, “Gypsy caught (Scott) with her trunk and hurled him to the ground,” according to the Johnston article.

“Using her front feet, she stomped the life out of him. Shea was contacted at once. He hurried back to the show to be greeted by Gypsy with happy snorting and trumpeting. She held him in her trunk gently, and appeared to be overjoyed to see him.”

But Gypsy’s love for trainer Bernard Shea was a temperamental one.

On a hot day in Smith’s Grove, Ky., Shea rode Gypsy to a stream so she could cool herself. There, Gypsy’s trunk grabbed Shea and shoved him underwater. Wriggling free, Shea subdued Gypsy in a “brutal” manner, which Johnston does not detail. “Shea quit the show after this incident, knowing it was only a matter of time before (Gypsy) would kill him.”

James “Whiskey Red” O’Rourke inherited the job of handling Gypsy for the W.H. Harris Nickel Plate Shows.

In New Orleans, Gypsy knocked O’Rourke to a sidewalk. She attempted to stomp him with her front feet. She broke three of O’Rourke’s ribs.

In another incident, she dislocated O’Rourke’s hip. On another occasion, after O’Rourke reportedly had several drinks, he disciplined Gypsy.

A smaller male elephant named Barney “became irritated. He waited until O’Rourke moved in front of him and then knocked (O’Rourke) down three or four times,” Johnston wrote. “The situation was laughable.”

Terror in Valdosta

On a Saturday morning, Nov. 22, 1902, the Harris Nickel Plate Shows arrived by circus train in Valdosta. Gypsy was billed as “The Biggest Born of Brutes,” a star attraction, the elephant that could play harmonica.

By this time, circus employees estimated Gypsy’s age at 65-67 years old, according to the Lowndes County Historical Society, adding the elephant weighed an estimated five tons.

The Valdosta show went well and “at the conclusion of an afternoon performance, the circus began folding its tents to go into winter quarters at Pine Park,” according to reports in The Valdosta Times.

“All day Saturday, O’Rourke had complained of being sick and in the afternoon he began to take quinine and whiskey,” according to local newspaper accounts.

Gypsy and O’Rourke’s history of mutual abuse was known and reported in local accounts of the era, but the reports added, “the elephant, in a more docile mood, had (in the past) picked the intoxicated trainer up and lifted him back onto her head when he had fallen off.”

In sour health, saturated with whiskey and quinine, O’Rourke reportedly drank a final sip of whiskey before climbing onto Gypsy’s head.

“Following a trip for a change of O’Rourke’s clothes, the elephant walked north up Patterson (Street) with the drunk man tottering on her head,” according to accounts.

They went one way, then another, and finally turned onto Central Avenue, away from the circus grounds. Residents yelled to O’Rourke that he was traveling in the wrong direction, but “he paid no attention.”

The elephant and rider attracted the attention of Valdosta Police Chief Calvin Dampier, who also yelled for O’Rourke to turn the elephant around. O’Rourke answered with “an incoherent mumble,” according to Johnston’s account.

At the Central Avenue-Toombs Street intersection, Gypsy abruptly stopped and O’Rourke fell to the cobble-stoned street.

“For a long while, O’Rourke lay on the street under the huge elephant’s trunk. He failed to get up. (Gypsy) hesitated to lift him back to her head,” according to The Times. “Then, slowly, deliberately, the mammoth beast kneeled down over O’Rourke and crushed his body. She then rolled the limp body along with her trunk and tusks for some 50 yards.”

What happened within the next few minutes is debatable due to differing accounts.

The Valdosta Times and Johnston’s article report that Chief Dampier alerted the circus of the freed elephant and O’Rourke’s death. Circus employees, including former trainer Bernard Shea, attempted driving Gypsy to a railway boxcar, but a locomotive blast and the gathering crowds spooked the elephant.

In a 1973 article for the Lowndes County Historical Society newsletter, E.D. Ferrell wrote that one of Gypsy’s tusks broke off while dragging O’Rourke along the street. The pain enraged her.

Whatever happened, accounts agree that Gypsy went berserk, sending the crowds running for cover. She wrapped her trunk around a light pole and burst the lights. At the Christian Church, Gypsy attacked a circus clown with her trunk and threw him an estimated 30 feet. The clown was injured but survived the attack.

For more than two hours, “… Gypsy took control of the whole street,” according to newspaper accounts. “She would charge at the crowd, then hurl loose bricks and timber through the air and all the while she was emitting a blood-chilling elephant cry … Terrified Valdostans tried to get the women and children off the streets.”

Gypsy’s rage wasn’t focused on women and children. Gypsy seemed angry with the circus people. Two animal trainers tried killing her. Using pistols, they shot Gypsy several times, but “the bullets did no harm and seemed to make her much madder.”

By night fall, the rampage continued.

“It was an eerie sight,” according to The Times, “the huge elephant thundering up and down the streets past the street lights, then into the shadows, no one knowing where she would strike next.”

Hunting Gypsy

Police Chief Dampier went home to fetch his Krag-Jorgensen rifle, which he had carried in the Spanish-American War. By 11 p.m., Dampier had a posse and the approval of the circus to kill Gypsy. Some Valdostans briefly pleaded for Gypsy’s life but these pleas were soon silenced by the elephant’s continuing rampage.

“Dampier and his posse were on the top of the (circus) ticket office,” Johnston claimed. “… Dampier drew his Krag-Jorgensen rifle and fired two or three shots.”

The Valdosta Times claims Dampier fired the shots while Gypsy stood in a vacant lot. Ferrell’s account does not mention Dampier shooting at this point.

Gypsy crashed through a gate in the rear of the fairgrounds. Though Johnston reported that Dampier called off the posse until morning, Ferrell and The Valdosta Times reported the posse chased Gypsy, cornering her at Cherry Creek, which all accounts agree was the location of Gypsy’s last stand on Sunday morning, Nov. 23, 1902.

Some say Dampier steadied his rifle on a fence. Others claim he took aim while his rifle rested on a pine tree. Johnston’s article noted that Dampier killed Gypsy with one shot at Cherry Creek. The Valdosta Times wrote that Dampier dropped Gypsy to her knees with one shot before finishing her with a second shot. Ferrell wrote that Dampier “pumped several shots into her body.”

An estimated 3,000 people visited Cherry Creek to see the dead elephant. “Scarcely anything else was talked about on the streets,” The Times reported.

Gypsy was buried in several holes, only paces from where she fell. Though axes were used to chop the elephant carcass into pieces, a team of six horses had to drag the remains to the graves.

That same afternoon, James “Whiskey Red” O’Rourke’s casket was carried to Sunset Hill Cemetery in a hearse pulled by six horses.

For several years, when the circus annually returned to town, its employees placed a wreath on O’Rourke’s headstone until the Harris Nickel Plate Show went out of business.

“Gypsy’s death was a tragic day in Valdosta history,” The Valdosta Daily Times noted in 1959. “It gave the city more publicity than anything else that had ever happened here. Newspapers all across the country carried stories of the ‘monster elephant in a piney woods town.’”

In other cities, some newspapers accused Valdostans of everything from staging the event by turpentining a tail to a steer. One out-of-town newspaper claimed “Valdosta mob violence caused Gypsy’s death.”

In a 1902 Valdosta Times editorial, C.C. Brantley noted it was not mob violence that led to Gypsy’s death adding that circus employees fired the earliest shots. Many accounts of the incident also refer to Valdostans reacting to Gypsy’s death with a mix of relief and sadness.

From those emotions and the many accounts of the elephant’s rampage, a legendary story was born that has been a source of interest for more than a century.