Guardians of the shore

Published 5:00 am Sunday, September 27, 2015

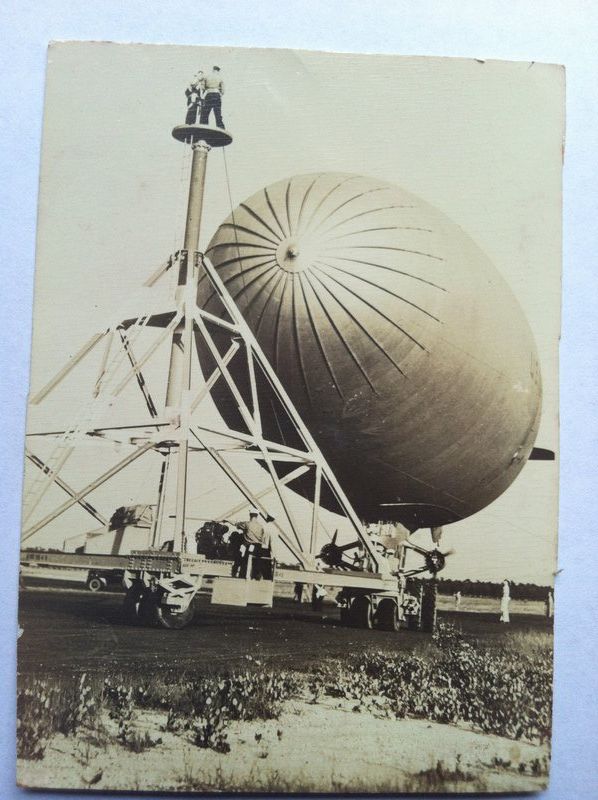

- Submitted photoDr. Raymond Cook of Valdosta piloted Navy blimps during World War II.

VALDOSTA — With exception of Pearl Harbor, the public thinks of World War II as being mostly overseas.

Yet, German submarines regularly harassed the East Coast and Atlantic shipping lanes. U.S. shore patrols kept vigilant watch for submarines and the possibility of an Axis invasion.

Trending

Dr. Raymond Cook, 96, of Valdosta is best known as a retired Valdosta State English professor, but he was a guardian of the shores during World War II, though he would never use such words to describe himself.

Specifically, Cook was a blimp pilot.

Blimps patrolled the Atlantic coast.

Best known as marketing tools now, think Goodyear, blimps were used for aerial surveillance and to escort American ships in various parts of the world during World War II.

A blimp is a non-rigid, lighter-than-air airship filled with helium, rather than highly flammable hydrogen which filled the doomed zeppelin Hindenberg. A blimp is a dirigible. A dirigible is a lighter-than-air craft that can be non-rigid, semi-rigid or rigid.

“All blimps are dirigibles,” Cook said, “but all dirigibles are not blimps.”

Trending

During approximately 37,000 flights in the war, Navy blimps “escorted 70,000 ships off coasts of America, Canada, Brazil, Gibraltar, Mediterranean, Africa,” according to information provided by Cook.

From all of the flights, only one life was lost due to a shark attack following the shooting down of a blimp; 26 blimps were lost but only one to enemy fire.

Overall, 83 lives were lost via the blimp patrols, but they had nothing to do with enemy action. For example, the deaths were related to instances such as four lives lost to electrocution via touching handrails, or three killed by blimp propellers, or three deaths via hydrogen fires.

There were dangers associated with blimps, but the danger was relative, Cook said.

“It was safer than being on Anzio Beach,” Cook said, referring to a battle with thousands of Allied casualties.

Cook regularly piloted an MShip blimp.

Top speed: 60 miles per hour.

The MShip was 293 feet long, filled with 647,000 cubic feet of helium, compared to the 803 foot length and 7 million cubic feet of hydrogen of the Hindenberg, Cook said.

Near the war’s end, “the U.S. was planning the ZRCV with 10 million cubic feet,” Cook said. “Now that would have been a big airship.”

The MShip had an enclosed cabin beneath the blimp. An eight-man crew operated the blimp during Atlantic patrols, Cook said.

Crews were not assigned to specific blimps. They flew whichever MShip was available at the time of assignment.

Some MShips handled better than others.

“All blimps are eccentric but some are more eccentric than others,” Cook said.

While some plane pilots named their aircraft after girls, blimp pilots had no romantic notions regarding their airships.

“No. No names,” Cook said of the blimps, “but we did call them some things I can’t repeat here.”

As a child, there was no grumbling, only awe, as he witnessed his first airship, the Shenandoah.

The Shenandoah was the first of four Navy rigid airships. First airship to cross the North American continent. Fifty-seven crossings. Only 57. Storms over Ohio tore it apart mid-air, killing 14 crew members.

The Shenandoah fell.

But the disaster remained in the future on the day when young Raymond witnessed the Shenandoah in Georgia.

“As a boy, as a child, I remember the school going outside to see the Shenandoah,” Cook said. “At more than 500 feet long, it virtually filled the sky. Very impressionable to a little boy.”

Though impressed, Cook did not plan on becoming an airship pilot. He studied English. He became a teacher. By 1941, Cook taught high school classes in the Georgia town of Eatonton.

On the day after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, Cook recalls eating lunch at school, learning of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s statement of America being at war.

“I thought, I’m going to be drafted,” Cook said. “That’s it. I’m dead.”

Making various contacts, Cook arranged to join the Navy. He had hoped to pilot planes. The air seemed safer than the infantry, he said.

Low weight nearly kept him out of the Navy. An induction board member told him to go home and eat bananas. Lots of bananas. Cook did. He was still slightly under weight the next day, but the induction board accepted him into the Navy.

“Bananas are still one of my favorite foods,” Cook said. “They saved me from the infantry where I may have died.”

Other than his boyhood memory of seeing the majestic Shenandoah, Cook knew nothing about blimps. With the possibility of earning the Navy’s “wings of gold” in a few months and becoming an officer, Cook learned about blimps.

By 1943, Cook piloted blimps off the Florida coast.

One patrol lasted approximately 24 hours. In the incident where the blimp was downed by enemy fire, Cook was assigned to patrol the same region off the shore of Miami.

Filled with helium, Cook said crews did not worry if enemy fire punctured the lower balloon-like portion of the blimp. A blimp can still maintain altitude with a puncture below.

Worry came if bullets punctured the top of the blimp. A hole in the top meant the helium could escape and the blimp would drop.

At times of radio silence during missions, the blimps used pigeons to communicate their findings to shore. Cook recalls one pigeon being released far from shore.

Headquarters later wanted to know why the blimp had never contacted base during radio silence. Upon returning to base, the blimp crew discovered the pigeon had perched on the blimp’s tail, having apparently refused to fly over so much ocean.

Cook flew numerous missions from 1943 through about Christmas 1944.

By then, with the Allied invasion pushing from the west and the Russians pushing from the east, Germany could ill afford the submarine program off of America’s coast. As the submarine threat faltered, the blimp surveillance program disbanded and its crews were assigned other duties.

Before Cook could leave for an assignment in the Pacific, a diagnosis of hypoglycemia sidelined him until the end of the war. After the war, Cook continued his education, including earning a doctorate, eventually teaching English at Valdosta State.

As for the war, Cook remains philosophical 70 years after its conclusion.

“I had never met a German or a person from Japan so I had no animosity toward them,” Cook said, “but some of the men I served with, I didn’t like.”

As for blimps, he has no interest in climbing aboard one, even if offered.

“I prefer being on the ground,” he said. “I have no interest in doing it again. Been there. Done that.”