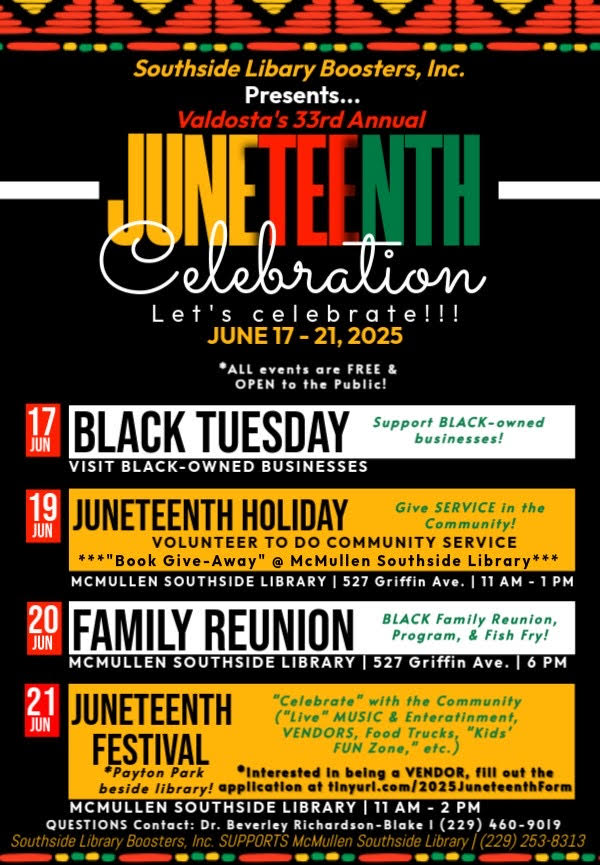

New Face of Addiction: Opioid crisis takes personal toll

Published 9:00 am Thursday, November 9, 2017

- Opioid deaths JPG

Ramona Osborne doesn’t recall the circumstances of the drug overdose that nearly killed her.

The Moultrie resident just remembers waking up in a hospital and learning she had been on life support for nine days.

“They told me they did not expect me to wake up,” Osborne said in an interview. “My last rites were read. They (her family) were planning the funeral. It’s like you were done.”

For Osborne, the winding path to her near-fatal overdose started with alcohol. When the then-dental hygienist couldn’t mask the smell from patients and dentists, she switched to prescription painkillers.

Her new pill habit, though, eventually became unsustainable. For her, it took hundreds of dollars a day to buy enough pills to satisfy her urges.

“I resorted to buying it on the street,” the D.C. native said.

That then led her to heroin, which cost her $10 a bag and would last longer.

Osborne fell into opioid addiction in the 1990s, when the epidemic — which prompted President Donald Trump to declare a national public health emergency last month – was still in its infancy.

She has now been sober for more than three years and works at the south Georgia treatment center where she found sobriety. She’s also a frequent speaker for Narcotics Anonymous, sharing her story of recovery.

But for many Georgians struggling with opioid addiction today, there have been no happy endings.

Crisis mode

Georgia’s death toll for opioid-related overdoses has been steadily rising for years.

A decade ago, just 242 people overdosed on opioids, according to state Department of Public Health data. Last year, four times as many people died, with most of them overdosing on prescription painkillers.

The carnage here may not collectively be as devastating as what has hit other states, such as West Virginia, where opioids killed 36 out of every 100,000 people in 2015. Nationally, prescription opioids, heroin and fentanyl killed more than 33,000 people in 2015 – the highest count on record.

But the increase in overdose deaths in Georgia has been significant enough to set off alarm bells in Atlanta, where state officials use words such as crisis and epidemic.

It’s also at least part of the reason the Georgia Bureau of Investigation just opened the doors of its expanded morgue, which can now hold up to 100 bodies at a time, up from 25. It was a $6.7 million project.

Vernon Keenan, director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, said he’s had to tell county coroners to wait a few days to bring bodies to Atlanta for autopsies because of space constraints. He points to opioid overdoses as a factor.

Toxicology tests are more complex and time-consuming, with the state lab often screening for multiple drugs in one overdose case.

“More Georgians die from prescription drug abuse than we do from illegal drugs,” Keenan said Wednesday after a ceremonial ribbon cutting outside the Atlanta facility. “So we do a tremendous amount of work in this area.”

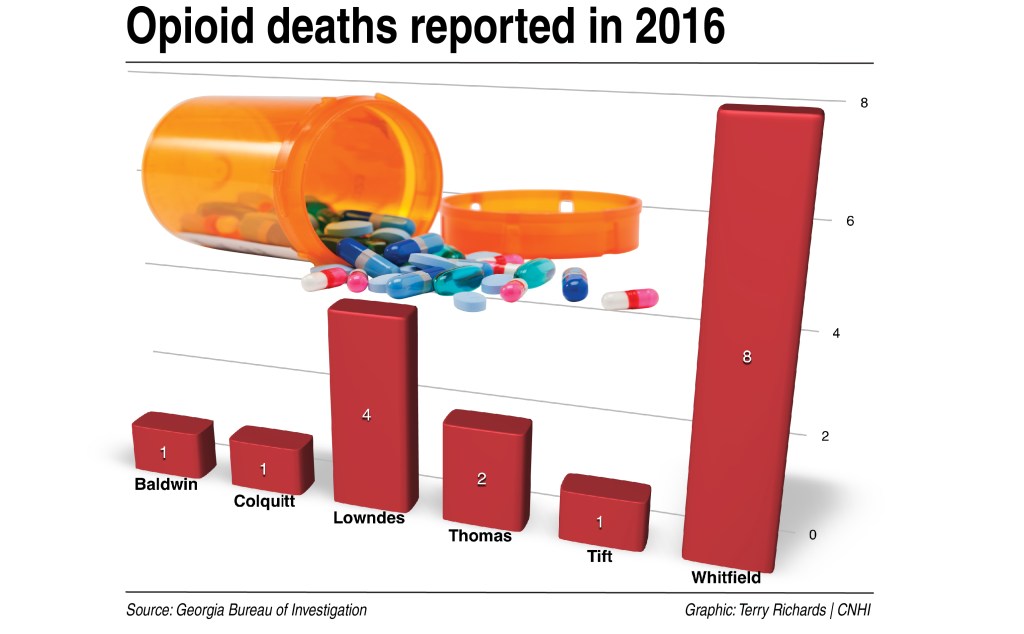

No county spared

No area of the state has been left unscathed. That includes every SunLight Project coverage area, which includes Thomasville, Valdosta, Moultrie, Tifton, Milledgeville and Dalton.

And no demographic is invulnerable, although white Georgians are dying at a much higher rate. Both young and older adults have perished in alarming numbers. Some of them had prescriptions for the drugs that killed them.

“It cuts lives short,” Thomas County Coroner Don Shiver said. “You’re not supposed to bury your child. Others are left fatherless or motherless.”

In Thomas County, which is home to about 45,000 residents, eight people have overdosed on opioids so far this year. All of the deaths were unintentional.

In Whitfield County, home to Dalton, there have already been six overdoses involving opioids this year. One of them was a 56-year-old white woman who accidentally died after taking a combination of eight different prescription drugs.

A 25-year-old black man in Tift County overdosed on his prescription oxycodone. He was one of three opioid-related overdoses from the last year or so in a county home to about 41,000 people. In Colquitt County, a 28-year-old white man accidentally died last year after taking morphine.

In Lowndes County, where Valdosta is located, three different prescription drugs, including oxycodone, surfaced in the toxicology results of a 57-year-old white woman who overdosed this year. She is one of two opioid overdoses this year.

A 43-year-old white woman overdosed last year on prescription morphine and fentanyl in Baldwin County, where Navicent Health Baldwin in Milledgeville has treated 51 patients so far this year for a suspected drug overdose.

“Every county in the state’s been touched by this,” Keenan said.

A deadly comeback

In Whitfield County, prescription drugs aren’t the biggest culprit. That distinction goes to heroin.

“The big things are a drug we haven’t seen for a long time, heroin. That’s making a comeback. And the other thing is fentanyl,” said Scott Radeker, director of Hamilton Emergency Medical Services.

It’s not uncommon for people to start with painkillers and then later turn to heroin because of the cost. Still, about 60 percent of all opioid overdose deaths in Georgia last year were tied to pain medications.

Keenan said the state saw an increase in heroin use after lawmakers tightened up regulations on pill mills in Georgia.

“It was an economic thing,” he said in an earlier interview. “The supply of prescription drugs was becoming much more limited and people could feed their addiction by switching over to heroin, which is substantially cheaper.”

Whereas an OxyContin pill might go for $60 on the street, a dose of heroin might be found for $6, he said.

Still, prescription drugs are the most common killer, Keenan said.

“We’re having as many problems with prescription drugs as with illegal ones,” said Lowndes County Sheriff Ashley Paulk, who said he’s seen an uptick in cases involving opioids.

Paulk, who also served as sheriff from 1993 through 2009, recalled “a lot of abuse and doctor-shopping” in those days.

“The drug companies didn’t make it clear that these drugs were highly addictive,” Paulk said.

The sheriff, for one, says he is now more wary of painkillers. When he recently had back surgery, he told his doctors he didn’t want to use opioids for the pain. Instead, he said he’s getting by with Aleve.

For Part II of this series The New Face of Addiction, see the Tuesday edition of the Valdosta Daily Times.

GBI: Fentanyl kills ‘graveyard dead’

The fentanyl was the size of a few grains of salt.

That was all it likely took for 18-year-old Dustin Manning and 19-year-old Joseph Abraham, who lived in the same Lawrenceville neighborhood in metro Atlanta, to overdose alone in their bedrooms on the same morning in May.

The toxicology reports have not been released yet, but Dustin’s mom, Lisa Manning, said Thursday that she was notified her son’s death was caused by meth laced with the fentanyl.

“You think it will never happen to your child,” Manning said. “I was that person. My kid grew up in the church. He was in the youth groups. He told me at the age of six he wanted to be a minister.”

Manning described her son, who was homeschooled until he went to high school, as someone who had many friends and who loved baseball.

He also struggled quietly with depression. But Lisa Manning recalls her son, who had recently received his GED, as being in an especially good mood the night he died. He seemed excited about life, she said.

That’s why she’s so sure Dustin did not knowingly take fentanyl that night.

It’s becoming a more familiar story throughout Georgia, with heroin and counterfeit pills laced with the deadly drug surfacing all across the state, including in areas far beyond the metro Atlanta area.

The growing threat of fentanyl is the reason ambulances in Tift County have doubled up on the amount of naloxone, an overdose reversal drug, that is kept on board ambulances, said Junior Horton, Tift County EMS director.

It was a recent change, Horton said, and one made because a single dose of the reversal drug won’t help someone who has overdosed on fentanyl. Also, first responders need it for their own protection, since the powder or residue can be absorbed through the skin.

“The margin between being high on fentanyl and being dead from an overdose is very narrow,” Vernon Keenan, director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, said in a recent interview. And using heroin laced with fentanyl, he said, will “kill you graveyard dead.”

Fentanyl has accepted medical uses as a painkiller. It has also an approved analog called carfentanil that is typically used as a tranquilizer for large animals and can be 10,000 times stronger than morphine.

The drug is so powerful that law-enforcement officers now commonly wear protective clothing, such as gloves and masks, when there’s a potential encounter. Keenan said undercover agents are also seeing some drug dealers wear such protection.

The potency of the drugs available on the street manifested itself perhaps most vividly this year when a batch of fake Percocets caused mass overdoses in central Georgia in June, believed to be responsible for killing five people and hospitalizing dozens of others.

The little yellow pills contained cyclopropyl fentanyl – which is an analog that had never been seen before in United States – and another synthetic opioid that is seven and half times stronger than morphine.

Clandestine chemists overseas design these fentanyl spinoffs, in part, as a way to skirt drug laws. Some users may also seek it out for a more intense high.

To date, at least six different fentanyl analogs that have been smuggled into the United States have been flagged in the state’s crime lab.

“That’s coming out of China, and it’s cheap, cheaper than heroin, so what the dealers are doing is cutting the heroin with fentanyl or carfentanil,” said Greg Stinnett, director of the pharmacy at Hamilton Medical Center in Dalton. “It saves them money and makes the heroin even more potent.”

But that also dramatically increases the risk for the user.

“You can’t even try it once anymore,” Manning said during an emotional press conference called by state Sen. Renee Unterman this summer. “The drug of yesterday is gone.”

Manning, who has worked at treatment centers, said Dustin started drinking at the age of 12 before starting to smoke marijuana and eventually taking Xanax and the old painkillers he found in their medicine cabinet. He later moved on to harder drugs, such as meth.

Manning said she and her husband, who had sought treatment for their son, gave Dustin a drug test the night before his death. It came back clean.

“It used to be you can relapse but you have some more chances,” Manning said. “You don’t have another chance now with all this stuff out there.”

Manning and Joseph’s mother, Kathi, both live in Unterman’s Gwinnett County senate district.

Kathi Abraham attended a forum on opioid addiction, sponsored by Unterman, the night before her son died. It was the first time she had heard of fentanyl.

Abraham said her son, who loved to fish and aspired to be a tour guide, may have first become hooked on painkillers after having his wisdom teeth pulled in eighth grade.

She was told traces of heroin, meth and fentanyl were found in his system when he died.

“I hope the more that we share our story and talk openly, the more lives are going to be saved,” Abraham said this week. “I’m not ashamed of this and I’m not ashamed of my son.

“I hope people will be able to speak out about this, and if you know somebody, not to keep it behind closed doors,” she said.

She knows a little about that. A public school teacher, she tried to keep Joseph’s addiction private. Now, she said she wants to tell everyone, especially other parents. She urges parents to start talking to their children long before they enter high school.

Unterman, a Republican who chairs the Senate Health and Human Services Committee, said the teens’ deaths brought the issue home for her.

“Now, you make one mistake and you’re dead. There’s no turning back,” she said. “There’s no saying, ‘I’m sorry. I won’t do it again. I’ll get some help.’ You’re dead. You’re gone. Your family is torn apart.”

Unterman, who says opioid addiction is her top issue right now, said senate leadership is developing a legislative package for next session, which starts in January. The crisis, she said, has a profound impact on health care, education and social services in the state.

This push will come on the heels of the 2017 legislative session, which brought increased scrutiny of prescriptions written in Georgia and broad access to naloxone.

“Everything about this epidemic affects every family in the state of Georgia whether people realize it or not,” Unterman said. “At some point, it will affect you. It will affect you when you either pay your taxes or when you have a loved one to die.”

The SunLight Project team of journalists who contributed to this report includes Patti Dozier, Alan Mauldin, Charles Oliver, Will Woolever, Jessie Box, Eve Guevara, Jordan Barela and Terry Richards. To contact the team, email sunlightproject@gaflnews.com.