On the Streets: Lowndes County homeless population grows

Published 3:30 pm Friday, March 8, 2019

- Research shows the amount of homeless people helped through Rapid Re-Housing and Prevention programs last year.

VALDOSTA — Burn marks and blisters on his hands tell Jimmy Pratt’s story.

Living only with his boxer-bulldog, Dixie, at a campsite, a recent fire threatened Pratt’s home in the woods.

Trending

Though he attempted to put the fire out himself, he said he lost everything — including the tent where he lived.

“I didn’t have anything except for what I had on my back,” he said.

Pratt is one of the 47 people assisted by Lowndes Associated Ministries to People last year in its street outreach program. The homeless shelter served 12 people in its program in 2017.

Lowndes County agencies say the homeless population is on the rise.

LAMP’s client number increased from 887 people served in 2017 to 1,052 people served last year, according to the nonprofit organization.

Man on the Street

Trending

For Pratt, he said he went from living with his grandmother to being homeless.

The South Carolina native has been homeless on and off since the age of 18, he said, naming drug abuse as the cause.

“Drugs led to me being in the position that I am in now, but I’ve been clean for a couple of years now,” Pratt said in an interview earlier this year.

As a child, he constantly roamed the outdoors, he said, adding he was “pretty much” raised in the streets.

“I would stay out on the street a lot at nighttime,” Pratt said. “As far as the transitional period goes, from living in a house to being homeless, it wasn’t so bad because I really picked up on it.”

Pratt has lived in Georgia for about 30 years.

Last year, while living in Valdosta, he was working in Florida when an electrical accident forced him into homelessness again.

Pratt was living in a house at the time of the work accident.

“I was doing some tree work and I got electrocuted by a power line,” he said. “When all of the electricity came out of the bottom of my feet, (it) left big holes.”

Pratt’s recovery has been a long road, he said.

“It’s been like 13, 14 months since my accident and I’m just now getting back on my feet,” he said.

“Hopefully, soon, I’ll be able to search for work.”

Pratt is skilled in carpentry, concrete work, trimming, landscaping, heating and air and other forms of construction, he said.

Though Pratt’s campsite is four miles from LAMP, he refuses to live there because pets are not allowed.

Homeless people often decline shelter because of pets; Tyrese Sherman, LAMP street outreach coordinator, said it is a major problem.

“The people that live in the woods, if they have a pet, they will not leave their pets,” he said. “So many times, it would be freezing cold and I would ask them, ‘come to the shelter.’”

They tell him no.

Meet Them Where They Are

Reasons why a person refuses shelter varies.

One thought is people living on the streets suffer from mental illnesses, said Feleica Harrington, LAMP executive director. “They will not be able to adapt with other people in communal living,” she said.

Some people — such as community members with post-traumatic stress disorder — find it difficult living in LAMP’s dormitory-style rooms with other people, she said.

“Lot of people in the woods, they’re suffering from PTSD; they’ve been to war,” Harrington said. “They have some type of addiction or some type of mental illness that keeps them from being able to co-habitate with other people in the shelter, and they would rather live outside.”

These are the people — the ones holding signs asking for spare change and the ones sleeping in the woods alone, Sherman visits to fulfill their needs. He begins with a simple question: What can I do to help you?

Their needs include clothing, food and possibly ways to cook the food.“Anything they ask for, I try to get,” he said. “Anything.”

If a person refuses shelter, Sherman said he strives to make living outside comfortable for him or her. Being rejected is a solemn moment for Sherman.

“You can’t believe a person would subject themselves to that condition,” he said.

To assist a person, he has to gain his or her trust. A lack of trust is a factor of homelessness, Sherman said.

The mission of LAMP’s street outreach program is housing people, Harrington said.

“You have to take baby steps to build that rapport, to get them comfortable to want to get our services,” she said.

Though Pratt refuses to live at LAMP, he uses its services occasionally, visiting the shelter to eat, get supplies and recently for shoes.

Pratt said he tried living with his sister at her home but discovered he’d rather live alone.

Due to his anxiety, he said he can’t be around a lot of people. Activities such as grocery shopping make him nervous, he said.

“I really enjoy camping,” he said. “It’s peaceful by myself.”

Dr. Ronnie Mathis is the executive director of South Georgia Partnership to End Homelessness. He, too, said not everyone will enter a shelter.

“We try to give those people that don’t make it to the shelter the services … beyond their reach” outside of the shelter, Mathis said.

Though Partnership is not a shelter, the program assists the homeless community by helping find housing.

Homeless Count

LAMP reported in January the homeless count increased by 27 percent last year.

Mathis, who began working with Partnership in 2009, said he initially thought the number of homeless people was tremendously high but has since come to believe the numbers are undocumented.

He said the amount is constantly changing and increasing.

Vanassa Flucas is neighborhood development/community protection manager.

She recently conducted a homeless count in late January in coordination with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD decides each year which part of the homeless population to count.

Last year, in Valdosta, they counted the “precariously housed.” Precariously housed is defined as people who reside in a structure that’s supposed to house people but belongs to someone else, such as living with a friend.

This year, Flucas and volunteers counted people who were living in areas not fit for human habitation, she said.

“They’re either living on the street, in tents, encampments, their cars, abandoned warehouses or buildings,” she said.

“In essence, you’re really not getting the true picture of the total number of homeless people because each year, you’re counting a different segment of the homeless population.”

Sources of Homelessness

“People in Lowndes County become homeless because they are working poor,” Harrington said.

To afford a “decent” home in Valdosta, at least two people with full-time jobs making “decent” money have to live there, she said.

Similar to Harrington, Mathis credits small wages and lack of “reasonable” deposits as to why a person may be homeless.

“That’s a barrier,” he said. “All of those things play a factor.”

Paige Dukes, Lowndes County clerk and public information officer, cites affordable housing as a cause of homelessness.

“We have a lot of homes on the market here,” she said. “There’s a very small percentage of them that are actual affordable housing options for people who are really starting with nothing and trying to work their family into a long-term home.”

Many clients sheltered at LAMP are single with no spouse and suffer from mental illnesses, depression and drug addictions; all of which causes barriers, Harrington said.

“Why wouldn’t you be depressed if you’re not making any money, and you can’t afford to feed your children,” she said, “and you have to be on assistance, and you lack the proper education to be competitive in the workplace.”

People who are homeless may come from foster care or poor broken families, she said. They are from various walks of life.

“It doesn’t matter who you are. Anyone can be affected,” she said. “Anyone can come across some type of hardship where they were possibly depending on a spouse that was the head of household.”

LAMP has housed Valdosta State University professors, lieutenant colonels, registered nurses and medical doctors.

Mathis said he believes mental health is a source of homelessness. Disability is another reason.

While substance abuse is a factor, it’s not a high factor, Mathis said. He said it is a small percentage of the homeless community.

Part of the homeless population consists of migrants, Lowndes County Commissioner Joyce Evans said. Evans is a LAMP board member.

“A lot of the homelessness that we have around here is from migrants that come from different areas, like people come from Florida and other areas, because they know we have a better program here to serve them,” she said.

“Program” refers to both LAMP and Partnership, Evans said.

What Can Be Done?

Both LAMP and Partnership receive funding for two programs, Rapid Re-Housing and Prevention, both through HUD.

Implemented last July, the prevention grant is for people who have received a court-ordered eviction, according to both groups.

The program aids residents at risk of becoming homeless but the help comes with specific conditions.

“If it’s not from the magistrate court, then you can’t use the prevention money,” Mathis said. “We can’t even move until we actually have the eviction notice from the court.”

Harrington said the court-ordered eviction applies to utility payments, too.

“Most people are going to pay their rent before they pay a utility bill,” she said. “If they pay their rent, then they’re not going to get a court-ordered eviction.”

Harrington said it is difficult for the shelter to help residents with disconnection notices.

Rapid Re-Housing is a program offered to residents who have gotten evicted but still have jobs.

Allotted funds will pay for a rent portion, a utility deposit and an application fee for a certain period. The grant includes a $50 spending amount for groceries and transportation to move, according to LAMP.

“We’re going to rapidly put them back into housing,” Harrington said. “We’re going to help them find a house that is specified for their income, so we’re not putting them in a place that exceeds their budget.”

Mathis said Partnership is required to exit residents out of the Rapid Re-Housing system following the 30-day mark. They have to get re-certified if further assistance is needed.

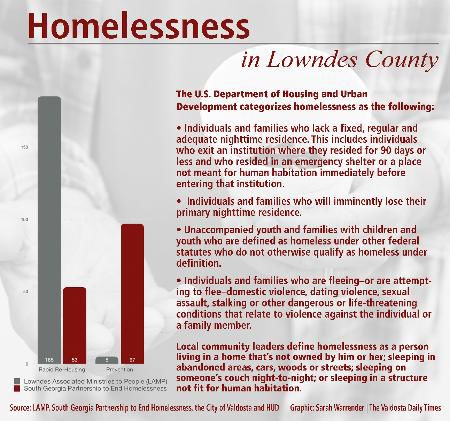

Last year, Partnership assisted 53 residents in its Rapid Re-Housing program and 97 in its prevention program, according to the organization.

LAMP helped 185 people in its Rapid Re-Housing program and five in its prevention program, according to the organization.

Commissioner Evans said churches also aid the homeless community.

She said housing vouchers are available through the Georgia Department of Community Affairs to assist people secure affordable housing.

Evans is collaborating with Lowndes County Commission Chairman Bill Slaughter and another commissioner to locate five or 10 unused acres in the county to build housing, she said.

Dealing with Federal Money

For the City of Valdosta, funding to combat homelessness starts with Flucas.

All grant applications for programs, such as Rapid Re-Housing, sent to DCA must first go through Flucas for approval, she said.

“They (the organizations) would come to us. I would say yes, this falls within our big master plan – and I approve it – and I allow them to go and apply for it,” she said. “This doesn’t mean that they get the funding. This just means that it gives them an opportunity to apply for it.”

The money is from federal funds but filters through the state.

“The city can’t afford to do programs for the homeless,” Flucas said. “That’s why we work with the other community organizations in our area – Salvation Army, LAMP, Behavioral Services and all of those that have programs that address homelessness.”

Flucas said the city does not have enough money in its HUD funding for these organizations, which means the groups can apply for funds directly through DCA to assist with the homeless population.

The city makes five-year plans that take into account programs offered by community organizations. The information helps the city know what it needs from HUD.

Partnership receives $30,000 of HUD funding for Rapid Re-Housing and $30,000 for its Prevention program from July 1 through June 30 each year, Mathis said.

Out of that money, $20,000 goes to each program respectively while the remainder goes into a data-entry system, he said.

Partnership also depends on contributions and donations.

Along with HUD money, LAMP receives an emergency solutions grant through DCA to fund its emergency shelter. The grant must be matched 100 percent, Harrington said.

The shelter funds itself from July through November with upfront money, which is later reimbursed, she said.

“We rely heavily on community dollars to float us during those months,” Harrington said.

The organization receives money from Greater Valdosta United Way, local donors and special events.

Holding onto Faith

Prior to cutting wood for fire, exercising his dog and carrying water to his camp, Pratt has a daily ritual.

“I wake up every morning, and I thank God for a new day,” he said.

His faith in Christ keeps him going each day, he said.

Sitting on the sides of roadways, holding a sign asking for money, Pratt said there are some people who will shout at him but there are also people with a good heart willing to help.

While holding the signs, pride has to go away, he said.

“You gotta get out there, and you gotta do what you gotta do because it’s all about survival out there,” he said.

“You just can’t lay down and take it. You gotta get out there and fly to make the money that you need to get something to eat or go to a doctor’s appointment.”

Pratt said a person will adapt to being homeless.

“Everything just comes natural after a while,” he said.

Pride kept Vanessa Ross Fertilus from telling her two children she was homeless.

Life after Homelessness

Fertilus became homeless last October following a nervous breakdown, she said, and her addiction to pain pills a few years ago.

“That’s what caused me to lose everything, those pills,” she said.

Following a stint with other organizations, the Nashville, Ga., native became an in-house client at LAMP. She cried her first day, she said, partly because of the number of children there.

“I just never thought that there would be children,” Fertilus said.

She had sunk into a depression after her breakdown, which fueled her anxiety the first night she stayed at LAMP, Fertilus said.

“Depression is real, and it had me to where I would just lay around all day,” she said.

While at LAMP, she volunteered to answer phones; she heard people’s stories and their pleas for help.

“If it wasn’t for my faith, I don’t think I’d be here,” she said. “I know I wouldn’t be here because there were times when I was suicidal.”

She would think about people in worse situations than her, Fertilus said.

“Someone didn’t have the opportunity to come into the shelter; they’re still sleeping on the street,” she said.

Last December, just before Christmas, Fertilus moved into her new apartment by way of LAMP’s Rapid Re-Housing, she said.

With previous experience working for a prison, Fertilus said she is willing to work anywhere. Her overall passion is writing.

“I don’t want this to be a revolving door for me,” she said. “I want to work. I’m able to.”

Fertilus’ said her experience has led her to help those on the side of the roadways because anyone can be homeless.

Call (229) 293-7301, or visit sgpeh.com, to learn how to volunteer at South Georgia Partnership to End Homelessness. The organization asks residents volunteer time; donate gently used clothing, furniture, household supplies, cleaning supplies, personal hygiene items and non-perishable “on-the-go” foods. People can also sponsor an individual or family by providing goods and services. Contributions can be mailed to P.O. Box 206, Valdosta, Ga. 31603.