‘Expendable Ones’: Prisons face COVID-19 in close quarters

Published 9:00 am Thursday, March 26, 2020

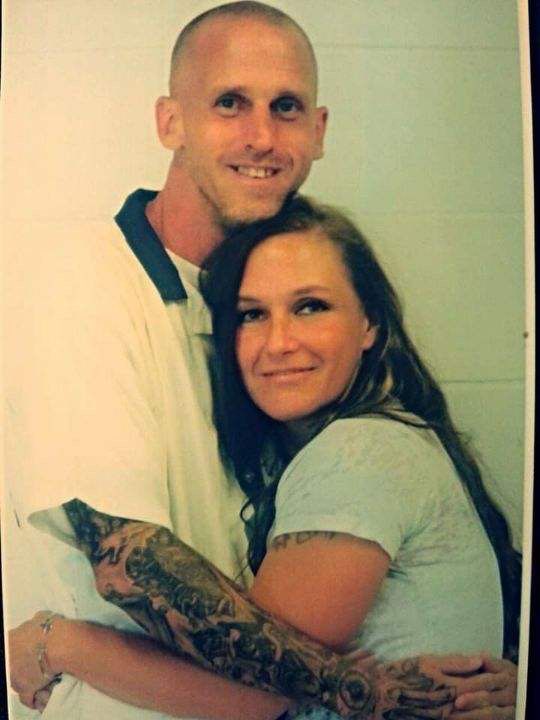

- Submitted photoMike Phillips and his wife Christi have been married since 2014.

VALDOSTA – Breathing has always been a challenge for Mike Phillips.

Inhaling, exhaling — the rhythm of life — goes unnoticed by most people.

Not to Mike.

Born with underdeveloped lungs, Phillips, 42, suffers from asthma and battles with bouts of double pneumonia on a yearly basis.

His respiratory issues make him especially vulnerable to respiratory disease like COVID-19 since people with asthma may be at “higher risk of getting very sick” from the coronavirus, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

So when Phillips, an inmate at Valdosta State Prison, was told to move away from another inmate sitting next to him in the prison’s medical clinic last Friday morning, he became understandably distressed.

Mike has been an inmate at the prison for nearly two decades, serving a life sentence without parole after being convicted of the murder of his stepfather-in-law at the time.

Nurses masked the inmate saying he had a fever and other symptoms of the coronavirus, then held an open conversation about how and where they would test the man, Phillips said in an interview with The Valdosta Daily Times.

Observing the debate about the next course of action, Phillips said he sat stupefied and uneasy, having just conversed side-by-side with the masked man.

“(It) kind of blew my mind away,” he said. “This has been coming down the pipe for months.”

Fortunately, that inmate tested negative for COVID-19, Phillips said, but he remains troubled by what he calls a lack of planning and safety measures taken by the prison to combat the coronavirus in day-to-day operations.

“There’s really no precautions being taken here,” Phillips said last week.

The state’s Department of Corrections has released statements saying prisons are taking steps to protect inmates and prison staff, but concerns over COVID-19 across Georgia’s prisons have been raised in the past week with prisoners not having access to extra soap or hand sanitizer, according to an Atlanta Journal-Constitution report.

Those concerns received additional attention when the first confirmed cases of inmates being infected with COVID-19 were reported March 20. The Georgia Department of Corrections confirmed three inmates at Lee State Prison in southwest Georgia tested positive for the coronavirus.

The Valdosta Daily Times sent repeated email and phone requests for comment but the state Department of Corrections responded with the same statement directing people to check information on the DOC website and social media channels due to the “rapidly evolving nature of COVID-19.”

In a section of the DOC website dedicated to COVID-19, it states soap and hand sanitizer have been increased in addition to “enhanced sanitation and cleaning protocols at all facilities” and designating “additional sanitation officers.”

The website states visitations and attorney visits to state prisons are suspended until April 10 to curtail potential transmission.

Facility operations, however, “will continue as normal with essential security staff reporting in as scheduled,” according to a memo regarding telework sent from Corrections Commissioner Timothy Ward to the office of Gov. Brian Kemp March 16.

In addition to corrections department guidelines, the CDC published new recommendations Monday for management of COVID-19 in correctional and detention facilities.

Phillips’ allegations conflict with the DOC website, particularly its claim regarding enhanced sanitation efforts.

After making several requests for additional chemical supplies last week, Phillips said he did not receive anything; however, prison employees come around once a day now with a one-liter bottle of cleaning solution, he said.

Contained in one bottle and used for 20 dorms, the liquid is poured on a rag for inmates to wipe down surfaces in their living quarters, Phillips alleged.

“I guess that’s their version of disinfectant,” he said.

Similarly, he claims there are no cleaning options provided for the one working phone used by inmates at Valdosta State Prison.

“I’ve got nothing to wipe this phone down with and who knows who’s touched it and been on it,” Phillips said.

Christi Phillips married Mike in February of 2014. Working in health care in Augusta, Christi is cognizant of the risks that an outbreak at Valdosta State Prison could pose to her husband.

“It’s giving me a little anxiety,” she said. “I’m trying to stay positive and really keep faith and pray that it doesn’t get in there.”

If Mike were to contract the coronavirus, communication is what particularly concerns Christi. Although she has medical power of attorney for Mike, she sits unsure if she would have to call the prison to find out about his health status if he becomes infected.

That thought has raced through her mind recently whenever there is a blip in their regular communication.

“When he hasn’t called me at a normal time that he calls, I’m thinking, ‘is he in the infirmary? Has he gotten sick?’” Christi said.

Mike Phillips is also concerned with the lack of social distancing. Social, or physical, distancing from other people is one of the most effective tools to prevent transmission of COVID-19, said Dr. Josiah Rich, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Brown University.

The practice rarely occurs at Valdosta State Prison, according to Phillips, where he says 10 inmates pack a small lobby waiting for the medical clinic or line up in tightly clustered formations when traveling to areas of the facility.

Phillips described what he called a curious incident Monday morning when prison staff corrected him for coughing into his hands instead of his elbow while in a line going from his dorm to the medical wing. Though staff properly informed him about coughing protocol, inmates stood shoulder-to-shoulder in line and stopped four separate times to ensure a uniform line stayed intact.

“It’s like cattle. … They don’t want any space between us at all,” he said. “How are you going to act concerned about this when I was just stopped four times and made to group up with everybody on the way up here?”

Phillips said prison guards wear gloves to pat inmates down, but he does not believe gloves are changed between each pat down.

Valdosta State Prison Warden Shawn Emmons did not respond to email requests for comment about Phillips’ accounts.

Just as concerning to Phillips, is what he considers to be an overall indifference by inmates about the COVID-19 outbreak.

Few inmates have voiced concern over the coronavirus, but Phillips, a self-proclaimed news junkie, has paid particular attention to COVID-19 as it dominates the news cycle.

“They don’t know enough about it,” he said. “They don’t watch the news. They don’t know what’s going on.”

Sports channels dominate the television, Phillips said, and NBA players such as Kevin Durant testing positive for COVID-19 yet still being healthy bolsters the wrongly held belief that inmates’ symptoms would be the same if they became infected.

Phillips foresees only one scenario that will instill more sober attitudes about COVID-19.

“To be honest, I think it’ll take a couple deaths before (inmates) take things seriously,” he said.

That scenario could be in the near future, according to Dr. Rich, who is also director and co-founder of the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights, an organization dedicated to “innovative correctional health research and programming.”

“Here’s what’s going to happen – the infection is going to get in there and then it’s going to spread like wildfire because it’s a correctional institution. That’s congregate housing,” he said. “And 80% of those people are going to be fine and 20% are going to be sick and 5% are going to be very sick. Some of those 20 and all of those 5 are going to likely be transferred out to the local hospitals, and that’s going to happen at a time when the local hospitals could be overrun.”

Based on the close proximity in prisons, Rich predicts a rapid spread of the coronavirus if it were to invade the prison.

“It’s going to be very, very hard to contain once it gets into the facility,” he said.

If COVID-19 strikes Valdosta State Prison or other Georgia prisons, a March 11 memo outlines the Department of Corrections protocol for handling potential coronavirus infections.

A memo titled “Communicable Disease Protocol,” sent by Betsy Thomas, Corrections director of human resources, to directors, wardens, superintendents and HR managers, identifies a four-step protocol.

The memo, obtained by The Valdosta Daily Times through an open records request, outlines the protocol saying it will verify the disease by requiring “a medical exam or health certification to confirm the illness”; the DOC will determine who is at risk for contracting the illness and consider any possible contacts, including people outside of the office or facility.

Corrections will advise the affected employee to seek medical attention from their attending physician and determine the severity of the disease “in order to justify decisions such as an emergency shutdown, or if a limited threat, only a review of a department or single area,” according to the memo.

It also addresses privacy by stating all employee medical information will remain private and Corrections will not provide names of infected parties or whether anyone is on leave via the Family Medical Leave Act or receiving accommodations through the Americans with Disabilities Act “unless there is a business need to provide this information, such as to a specific manager of an employee who is infected.”

While the three inmates at Lee State Prison remained the only Georgia prisoners diagnosed with COVID-19 earlier this week, according to the state corrections website, Rich does not see it as an isolated incident.

“I think ultimately the majority of correctional facilities across the world, it’ll get in,” Rich said. “It’ll spread quickly. It’ll tax the local health-care system.”

As for Mike and Christi Phillips, they cannot shake their uneasiness about the coming weeks.

“Mike keeps telling me, ‘I hope I do get to see you again’ because of his lung issues and he’s like, ‘if I get it, I know because I’m in here, I probably wouldn’t survive it,’” Christi said. “And every time he says that I’m like, ‘what do I say?’ I don’t know what to say to that because I do feel a sense of powerlessness.”

He sits and waits as one of the most vulnerable populations inside of what is arguably an already vulnerable prison population.

“We’re the expendable ones, especially for the older people in here and high-risk individuals like myself,” he said.