A doubly cruel death

Published 11:00 am Saturday, July 18, 2020

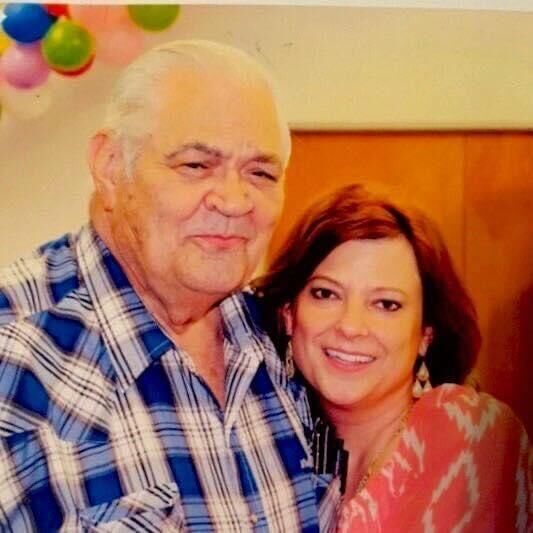

- Earl Lawson of Frankston, Texas, with his daughter Colette DeWitt. On June 25 Lawson became the first COVID-related death in Anderson County, Texas.

Earl D. Lawson’s death by COVID-19 was doubly cruel.

The disease not only took Lawson, 78, of Frankston, Texas, from adoring family members, but also robbed them of a proper farewell. After testing positive for the highly contagious coronavirus on June 17, Lawson became, except to medical staff, untouchable.

The retired engineer became Anderson County’s first COVID-related death June 25. Even during the viewing four days later, before Lawson was cremated, family had to remain 10 feet from the gurney that held his body.

“His isolation was unbearably painful for everyone,” said son-in-law Marc DeWitt, who lives near San Antonio. “Not to see your family again, or feel the touch of a human hand, was hard on everyone.”

Members of Lawson’s family urge East Texans to take the pandemic seriously. This week, Anderson County reported its second death from the coronavirus. In four days, new positive cases rose more than 50 percent to 302, including a record 204 active cases.

“In two weeks, my father went from healthy and strong to gone,” said Jevette Dansby, Lawson’s daughter. “This is serious. This is real.”

Lawson could have contracted the coronavirus in early June at an Oklahoma casino, where he and his wife, Doris, celebrated their 59th wedding anniversary. About two weeks after the trip, on Saturday, June 13, Lawson felt ill and feverish. After he fainted, Doris called 911. Lawson was taken to Christus Trinity Mother Frances in Tyler, where he was treated for a urinary tract infection, given antibiotics, and sent home.

Two days later, on Monday, Lawson struggled to breathe. His fever persisted. Doctors suspected the coronavirus. On Wednesday, Lawson was tested for COVID-19. Later that day, test results came back positive for a severe infection.

Aside from mild hypertension, Lawson, a strapping five-foot-eight and 230 pounds, was healthy and strong, according to his family.

“He had very few health problems,” said daughter Colette DeWitt. “He was definitely healthy enough to assume he would survive something like that. I don’t remember him even getting sick with the flu.”

A former aerospace engineer, Lawson worked on top-secret military projects in Dallas and California, including the Stealth B-52 bomber in the 1980s. He raised two daughters and a son, and doted over 10 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

“He was the nicest man you could ever meet,” Colette said.

After he retired, Lawson worked part-time at Burks Hardware in Frankston, happily explaining to his customers the difference between a machine bolt and wood screw. Daughter Jevette recalled often stopping by the store before she went to work at Tyler Junior College to say hi and visit for a minute.

Lawson also collected antiques, searching estate sales, auctions, and swap meets. His six acres outside Frankston included several sheds to store his treasures, prompting one friend to whistle the theme song to the 1970’s sitcom, “Sanford and Son,” whenever he pulled into the driveway.

On the day of his COVID-19 test, Lawson was essentially walled off from the world. Family members could communicate only through text messages or, occasionally, a brief phone call.

In those few words, they thanked him for the life he had given them. They told him they loved him. They told him they would take care of his lifelong partner.

Lawson received small doses of morphine to manage his chest pain. In his final days, as Lawson required more and more oxygen to breathe, doctors asked if he wanted to use a ventilator for life support. Lawson said no.

Daughter Jevette said she believes her father declined the ventilator because he didn’t want his family to have to make the hard choice of taking him off it.

“He didn’t want to impose that decision on us,” she said. “He didn’t want us to have any guilt or regret. Even then, he was thinking about us.”

A nurse said his last words were, “I love my family.”

Jeff Gerritt wrote this story as the editor of the Palestine, Texas., Herald-Press.