Lowndes honors Bataan Death March victims

Published 8:00 am Saturday, April 15, 2023

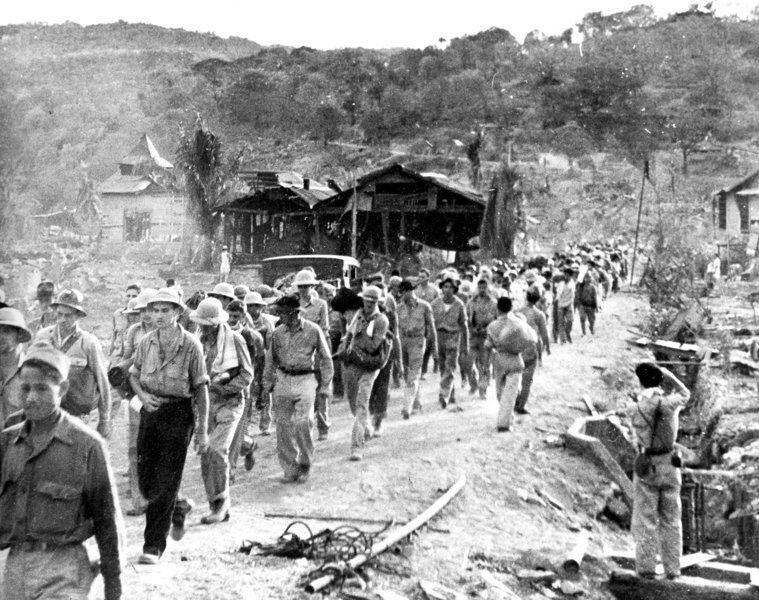

- n this 1942 file photo American and Filipino prisoners of war captured by the Japanese are shown at the start of the Death March after the surrender of Bataan on April 9 near Mariveles in the Philippines, during World War II. Hundreds of American soldiers and thousands of Filipinos died along the way.

VALDOSTA — For the third year in a row, Lowndes County honored thousands of U.S. and Filipino soldiers who died from cruel treatment in one of the most notorious atrocities of World War II.

A memorial march was held April 8 in memory of the victims of the Bataan Death March, said Brad Lawson, president of Georgia Christian School and a veteran who helped with the march.

Of the 104 walkers who signed up for the memorial march, about 74 showed up, an increase from the previous year, he said.

The walk consisted of three laps of 8.7 miles each and included a number of physical challenges along the way.

“Five people completed all the laps and all the challenges,” Lawson said.

The march was sponsored by the Lowndes County Sheriff’s Office; along with the LCSO, walkers came from Moody Air Force Base, the local fire departments, the Georgia State Patrol and the civilian world to raise $2,000 for a Rotary fund aiding law enforcement personnel in financial need, he said.

Lt. Rob Piciotti and Lt. Joe Dukes of the sheriff’s office came up with the idea of the memorial march and then made the event a reality, Lawson said.

The Georgia Beer Company sponsored the march for the second year and a live band, Uncle Murphy’s Law, played at the start/finish line. Leadership Lowndes and the Kerrigan Group were also sponsors, Lawson said.

History

The situation was looking bad for the United States in its first few months of the Pacific war. Only five months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan was sweeping across the ocean, conquering territories and driving ill-prepared American and British forces back.

In the Philippines, the Japanese 14th Army swarmed ashore on Dec. 22, 1941. Combined American and Filipino forces under the ultimate command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur battled their way back along the Bataan Peninsula; whoever controlled the peninsula controlled Manila Bay.

MacArthur was ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to evacuate to Australia on March 12, 1942, because of fears about how the Japanese would treat a captured enemy general, said Chris Meyers, professor of history at Valdosta State University.

American and Filipino forces continued to fight the Japanese invaders until, food and medicine nearly exhausted, U.S. Major Gen. Edward King Jr. was forced to surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army on April 9, with somewhere between 65,000-80,000 soldiers going into captivity. On the island of Corregidor at the entrance to Manilla Bay, U.S. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright surrendered about 10,000 troops to the Japanese on May 6.

This posed a problem for Japan’s 14th Army. They had taken far more prisoners than they had expected and they didn’t have transportation or provisions for that many men.

The result: Starting April 9, the prisoners were forced to march from 60-70 miles from the area of Mariveles to Camp O’Donnell, a former U.S. Army base which the Japanese would use to house prisoners of war.

Along the way, food was scarce. Water was scarce. Soldiers were cruelly abused by their captors. Those who collapsed from starvation were reportedly run through with bayonets or run over by trucks. Other soldiers were forced to sit in the hot sun with no helmets for hours in plain view of cool water; those who begged for water were shot. Hundreds of Filipino troops were executed after surrendering.

Many victims were randomly shot or stabbed by guards.

Japan had not signed a 1929 Geneva convention on the treatment of prisoners of war and the country’s military bushido code regarded anyone who surrendered as cowards unworthy of life.

Thousands more victims died from disease and barbaric treatment in prisoner-of-war camps until the conflict ended and the POWs were liberated by U.S. forces three and a half years later.

The aftermath

The Bataan Death March became a rallying cry for Americans after the U.S. government revealed what it knew about the situation in 1944. What information the U.S. had about the march was suppressed until then “because the government thought the public couldn’t handle it,” Meyers said.

There were calls in the Senate for the total destruction of Japan and the execution of the emperor, he said.

“It created a sensation,” Meyers said. “The public didn’t take kindly to it.”

Meyers said he was unaware of any official change in U.S. war policy that could be attributed to the death march; Japan was America’s No. 2 enemy during the war due to an official policy of defeating Germany first.

After war’s end, American forces tried and executed Gen. Masaharu Homma, commander of Japan’s 14th Army, and two of his top subordinates for war crimes for the death march. Homma’s defense was that he didn’t know about the horrors of the march until after it was over.