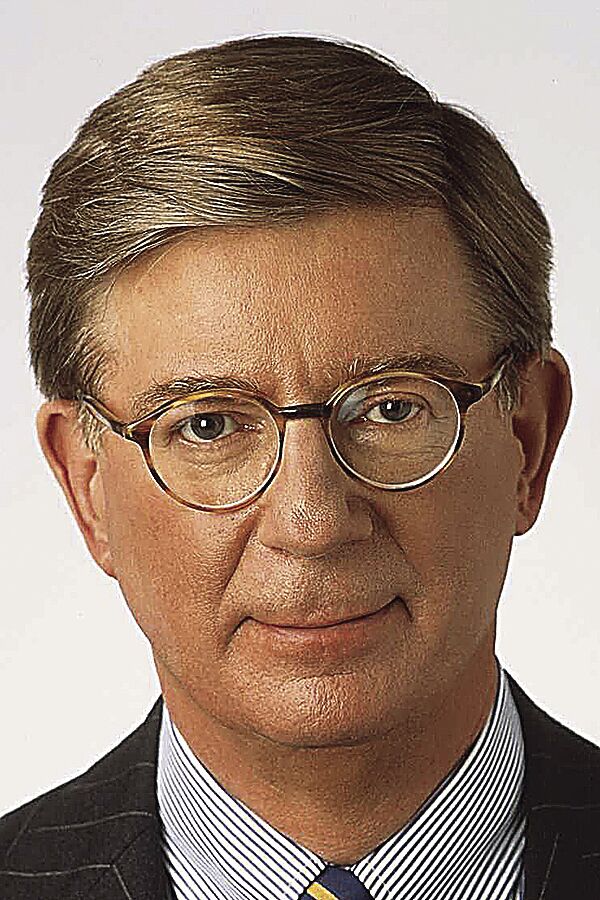

GEORGE WILL: Supreme Court makes a dangerous ruling

Published 10:32 am Thursday, May 23, 2024

- George Will columnist

Last week, “the least dangerous” branch (Alexander Hamilton’s description of the judiciary) did something dangerous. By ratifying the unprecedented structure of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Supreme Court incentivized additional slipshod congressional work that will feed the executive branch’s sense of entitlement to unaccountable discretion in making laws and policies. The decision, which some progressives will praise as “judicial restraint,” demonstrates that this anodyne phrase often denotes a dereliction of the judicial duty to compel the other branches to act constitutionally.

In 2010, Congress created the CFPB with a flamboyantly unconstitutional, and (Woodrow) Wilsonian, structure. The first president to radically criticize the Founding, Wilson was especially impatient with the separation of powers, one purpose of which is to inhibit unconstrained executive power.

Trending

The CFPB is empowered to regulate and define, without congressional hindrance, “financial products and services,” and “abusive,” “unfair,” “deceptive” or discriminatory business practices. The CFPB is a legislature, with enormous regulatory and punitive powers, lodged within the executive branch by a Congress uninterested in lawmaking or even oversight.

Last week, the court actually held, 7-2, that congressional progressives failed in their proclaimed attempt to pioneer a novel form of unaccountable autonomy for this appendage of the administrative state. Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Brett M. Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett and Ketanji Brown Jackson, said there is nothing importantly new about the CFPB’s structure. Either Thomas contradicts himself when referring to the CFPB’s various “novel structural features,” or he has unearthed a novel “original meaning” of “novel.”

The CFPB is doubly insulated from accountability through the appropriations process. The bureau funds itself by its director asserting its congressionally bestowed entitlement, in perpetuity, to up to 12 percent of the Federal Reserve’s operating expenses. These are not appropriated; they are assessments on banks and interest on the Fed’s holdings.

This, Thomas says approvingly, simply means nothing “forces” the CFPB “to regularly implore Congress” for funding. Implore? When did it become optional, even an indignity, for a federal agency to have to ask the people’s representatives for the people’s money?

The Constitution’s appropriations clause says: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” Thomas says in effect: A law established the CFPB, so the clause is satisfied.

Thomas, a strict originalist, says the Constitution’s words should be construed by their public meaning in 1787. Then, however, there was no federal institution remotely like the Federal Reserve, even as it was when created in 1913. And it then was nothing remotely like the freewheeling economic policymaker that the Fed is 111 years later.

Trending

Regarding the CFPB, Thomas makes originalism implausible by his mechanical (Jesuitical, casuistic, rabbinical, recondite — pick your adjective) attempt to tickle from the word “appropriation” an answer other than the obvious one: legislative control over the source and disposition of money to finance the government. Thomas’s originalist approach to legitimizing the CFPB is less a way of thinking than a way to avoid thinking about what “appropriation” should mean in the context of today’s administrative state.

Wandering deep in the weeds of medieval etymology (“Throughout the Middle Ages …”), Thomas misses the salutary point of judicious originalism, which is to discern and respect the appropriation clause’s original intent: to preserve the legislative branch’s core power in maintaining a Madisonian equilibrium between the branches — control of the public purse.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., joined in dissent by Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, also unpacks the meaning of “appropriation” but comes to the correct conclusion that the Constitution’s framers would be “horrified” by the CFPB’s structure, which reduces the appropriations clause to “a minor vestige.” The CFPB does not even have to return unspent funds to the Treasury but can build an endowment from unspent funds. As the majority reads it, Alito writes, the appropriations clause “imposes no temporal limit that would prevent Congress from authorizing the executive to spend public funds in perpetuity.”

Critics often call today’s court “imperial” — guilty of institutional aggrandizement. Actually, when the court insists that Congress use the powers vested only in it, such as control of public moneys and oversight of executive agencies, the third branch is telling the first branch to defend its primacy. The CFPB is yet another, but especially flagrant, act of self-diminishment by Congress.