Leading civil rights reporter dies at 89

Published 10:46 pm Tuesday, March 10, 2015

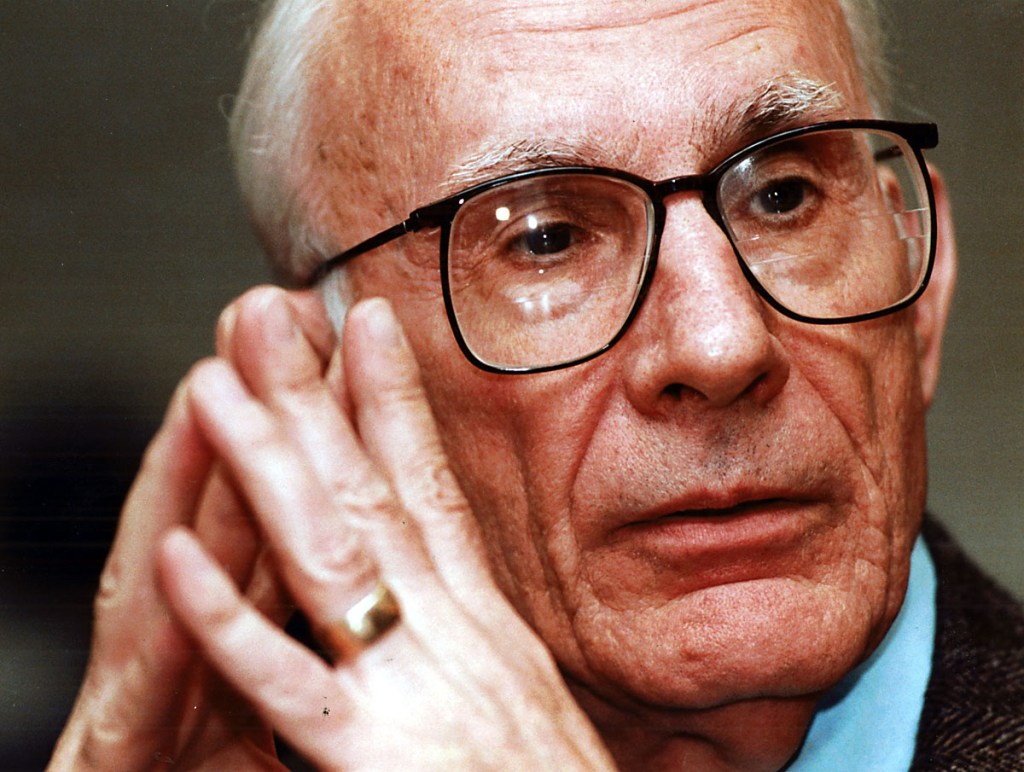

- In this Nov. 1, 1990 photo, Claude Sitton, who covered the South for The New York Times in the 1960s, poses for a photo, in Atlanta. Sitton, who was a leader among reporters covering the civil rights movement in the South in the 1950s and '60s and later won a Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary at The News & Observer, in Raleigh, N.C., died Tuesday, March 10, 2015. He was 89.

ATLANTA — In a 1962 article, New York Times reporter Claude Sitton described a voting rights meeting at a south Georgia church that was interrupted when the sheriff and his deputies entered, demanding information. One smacked his heavy flashlight into his palm while another ran his hand over his cartridge belt and revolver.

Sitton opened his account with a direct quote from the sheriff: “We want our colored people to go on living like they have for the last 100 years.”

After reading Sitton’s front-page report in The Times, then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy dispatched a team to Terrell County, Georgia. They sued the sheriff less than two weeks later, according to journalist Hank Klibanoff, who co-authored “The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle and the Awakening of a Nation.”

Sitton, who set the pace for reporters covering the civil rights movement in the American South in the 1950s and ‘60s and later won a Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary, died Tuesday. He was 89.

Sitton’s son Clint confirmed the death. Sitton had been under hospice care with heart failure. Sitton, a Georgia native, began crisscrossing the South for the Times in 1958 and became a leader among the reporters covering the civil rights struggle. “What made him the gold standard was that he went where other reporters didn’t go, and once he got there they followed,” said Klibanoff, former managing editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Sitton had joined The Times after working as a wire service reporter and then a press attache for the now-disbanded U.S. Information Agency, serving as a liaison between diplomats and the media.

Klibanoff said Sitton felt determined to give an honest account of the racial struggle in his native South and catapulted the newspaper into a leading role in covering the movement.

“It was not that Claude was some flaming liberal or liberator,” Klibanoff said. “He just liked a good story and liked to have it first. And frequently he was reporting on injustice — and they knew, on the civil rights side, that if The New York Times wrote about it, it would get attention from important people.”

Sitton “had both a physical and a mental toughness,” Klibanoff said. “He was not going to be intimidated … He felt that as a reporter — certainly as a reporter for the New York Times — it was essential for him to see with his own eyes and not to just be relaying what other people saw.”

Veteran Georgia journalist Bill Shipp, who was with Sitton during that Terrell County meeting, said when the sheriff asked Sitton to identify himself, Sitton replied, “I’m an American, sheriff. Who are you?”

“I thought, by God, that’s the end of us,” Shipp said. “He did not flinch and he didn’t back down. He was a brave man. But he was more than just brave. He was a first-rate journalist. When Claude was around, we all gathered in his room to compare notes. He was the kind of unofficial squad leader of the reporters covering civil rights.”

Sitton later served as The Times’ national news editor and became editor of The News & Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina. In 1983, his commentary for that newspaper won the Pulitzer Prize.