Remembering South Georgia’s ace

Published 9:00 am Sunday, October 21, 2018

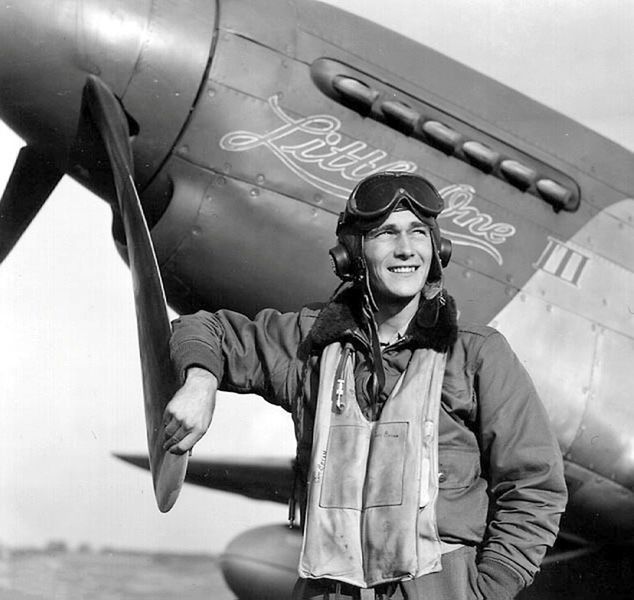

- Photo courtesy of Gregg Wagner Donald S. ‘Bush’ Bryan poses by his P-51 Mustang, which he nicknamed ‘Little One,’ for his wife. It is the plane he flew Nov. 2, 1944, when he downed five enemy aircraft in one afternoon. Bryan spent the last 30 years of his life living in Adel.

ADEL – High above war-torn Germany, World War II fighter ace Donald S. “Bush” Bryan led his flight toward an estimated 50 enemy aircraft.

A member of the 328th Fighter Squadron, 352nd Fighter Group, Eighth Air Force, Bryan was among an estimated 900 Allied fighters and 1,100 Allied bombers assigned to destroy key German petroleum refineries. Allied military intelligence believed it had misled the Germans regarding the appointed target. The Germans were not fooled.

Ten German fighter groups awaited the Allied air mission.

Capt. Donald S. “Bush” Bryan was already a flying ace, having downed a total of six enemy aircraft. He had cut his teeth flying the P-47 Thunderbird. As Allied forces approached the bombing destination at approximately noon, Nov. 2, 1944, Bryan piloted a P-51 Mustang, escorting bombers.

In what has been described as a brutal air battle, Bryan noticed the 50 approaching enemy aircraft, poised to attack the bombers.

“Captain Bryan led his flight into the center of the attacking formation of enemy aircraft where he closed on one and hit it several times,” according to a narrative from the U.S. Strategic Forces in Europe. “He was now alone and in the midst of many enemy aircraft who were unusually aggressive and attacking vigorously.”

Alone, Bryan made a pass at eight ME-109s. He “shot two down in flames and damaged another.” Under attack, “Bush” Bryan continued fighting.

“He finally destroyed five enemy aircraft and damaged two others, having engaged the last enemy with but a single gun operating.”

Five kills equals becoming an ace. Five kills in one battle made Bryan the rare “ace in a day,” Gregg Wagner of the Florida Friends of American Fighter Aces Association and one of three civilian board members of the American Fighter Aces Association said in a past interview.

Combined with his earlier kills, Nov. 2, 1944, made Bryan a double ace.

In issuing him the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions that afternoon over Germany, the citation notes his “extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy … His courage and outstanding aggressiveness in the presence of great danger were exemplary of the highest traditions of the Army Air Forces.”

By war’s end, Bryan had downed 13.3 enemy aircraft — the fraction means more than one pilot assisted in bringing down an enemy. Of the estimated 1,500 World War II aces, Wagner estimated maybe 30-some had more kills than Bryan.

Lt. Col. Donald S. “Bush” Bryan died following a brief illness in 2012. He was 90 years old.

‘Don was special’

To a generation of South Georgia children, Bryan was better known as the Candy Man than a World War II flying ace.

At Christ Episcopal Church in Valdosta, he always had Tootsie Rolls and candy for youngsters, Dean Failor, a long-time friend said in a past interview.

“He lit up when he was around children,” said Wagner, who met with Bryan on many occasions. “Children were important to him. He would always take time with them.”

The Lowndes High School Junior ROTC named its academic honor society in his honor. It is called the Donald S. “Bush” Bryan Kitty Hawk Society.

Bryan and his wife, Frances, led blood drives for decades. He volunteered as the male equivalent of a pink lady, giving his time for many years at the Memorial Convalescent Center in Adel.

“Usually aces can be cranky,” said Wagner who had worked with many of the pilots through the American Fighter Aces Association. “But Don never was. Don was special.”

He was not one to brag about being a World War II flying ace, but he wasn’t a veteran who refused to discuss his service either. If asked if he served in World War II, he said he flew planes.

“He never bragged,” Failor said. “If you asked him, he would tell you about things. But there were people who knew him for years who never knew he was an ace.”

Still, he had a fighter pilot’s competitive confidence.

Through his studio, High Iron Illustrations, artist John R. Doughty Jr. creates original art and prints of various military aircraft. He meets and works with many of these pilots, including Bryan.

Doughty recalled in a past interview creating one image where several pilots signed hundreds of prints at separate times. The first pilots took hours to sign the prints. A second pilot finished signing within a few minutes under an hour.

Doughty met with Bryan telling him the last pilot finished signing the prints in just under an hour. Bryan pulled off his watch and placed it in front of him. He signed the prints in 52 minutes beating the previous time.

Doughty laughed recalling Bryan’s remark. He said, I’m not going to let some bomber pilot beat a fighter pilot.

Meeting the Ace of Aces

In taking down five planes in one day, Bryan told Doughty that he was spared that day by using a maneuver called the “inverted vertical reverse.”

Bryan shared learning this move from a fellow pilot during a training exercise.

“When I was about to gun him, he had his plane to the point where it was about to stall,” Bryan told Doughty. “He would then pull back on the stick as hard as he could, apply full left rudder, and then pushed the stick forward. You sure experienced a lot of negative Gs doing this maneuver. The torque of the engine prop flipped the plane around and he would vanish.”

On Nov. 2, 1944, Bryan damaged two ME-109s, then shot down three.

“Then I encountered The Ace! I don’t know what that German was flying because his plane was hotter than any ME-109 I had encountered,” Bryan said. “My P-51D was the fastest Mustang in the 352nd FG — my crew chief did some ‘magic’ that hopped up the engine. Whoever this German was, he was good, very good, and he was getting close to clobbering me. I did the ‘inverted vertical reverse,’ and lost him. I didn’t go back looking for him. It took a while for me to calm down, but I engaged two more ME-109s and got them, the last one with only one gun firing. The entire engagement lasted only 15 to 20 minutes.”

On two other occasions, Bryan encountered the German Arcado 234 jet. On Dec. 21, 1944, flying the Mustang, Bryan damaged a German jet. On March 14, 1945, facing another Arcado 234 again over Germany, he defeated the jet in a dogfight, Wagner said, shooting it down.

The jet was Bryan’s last kill.

‘Little One’

Donald S. Bryan was born Aug. 15, 1921, in Hollister, Calif. The “S.” was for his middle name, Septimus, which he received because he was reportedly the seventh child.

Those who knew of his ace status may have assumed “Bush” came from his piloting years, but the story goes that he earned the nickname as a child.

One story claimed he received the nickname because he hid behind a bush as a little boy. Another story claimed it came from his growing up on a Paicines, Calif., farm and telling the cows to “bush, bush, bush” to get them to move.

He earned his pilot’s license while in college through the Civilian Pilots Training program. He joined the Army Air Corps on Jan. 6, 1943.

He flew numerous missions, aboard various planes. But each plane shared the same name: “Little One,” which was the nickname of his sweetheart, Frances Norman.

By the time, he flew the P-51 Mustang, he and Frances were married and he had named the plane “Little One III.” It is the same plane he flew taking down five enemy aircraft in one day.

Bryan continued serving in the military as the Army Air Corps became the Air Force. He and Frances had four sons. Retiring from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel, Bryan worked for an engineering firm. In 1981, the Bryans moved to Adel, where he designed and built their house. Frances passed in 2009.

Bryan continued being active. Shortly before his 90th birthday, he drove from Adel to Dallas then Ohio then Vermont then to North Carolina and back to Georgia to visit family and friends.

“He was fearless,” Failor said. “He was a man’s man. There was no guile about him. He told it like it was. … He never stopped.”

He became ill in spring 2012. The illness was a symptom of a more significant health problem. He eventually entered Memorial Convalescent Center where he died May 15, 2012.

He died a hero, but, as Wagner noted, he believes Bryan considered his greatest military performance a day that had nothing to do with becoming an ace but rather the event which Bryan described as “the only time I fired my guns in anger.”

Firing His Guns in Anger

On D-Day Plus One, June 7, 1944, Bryan and his wingman, fellow ace Bill Halton, along with two other Mustang pilots were assigned to escort waves of C-47s pulling gliders filled with para-troopers. The gliders were supposed to release to land in open fields.

Below were a series of hedgerows, which the Allies believed had been cleared; however, the Germans had an artillery piece hidden amidst the trees. Bryan would catch a small flash in the corner of his eye then a C-47 exploded, destroying it, the glider and killing approximately 50 men.

Another flash, another C-47-and-glider explosion, another 50 paratroopers dead.

Bryan and the three other Mustangs searched for the flashpoint’s origin. The gun kept shooting, planes kept exploding, paratroopers kept dying but they could not locate the flash’s location. For some reason, even with the planes being hit, the gliders did not release to safety.

With approximately eight C-47-and-glider combinations down, hundreds of men had died.

Bryan kept searching until the flashpoint was spotted. The four Mustangs converged on the spot. They fired until the Mustangs’ bullets cut through all of the tree cover like a buzz saw. They fired until the artillery piece was riddled with bullet holes, slagged by the heat of the Mustang ammunition.

They fired until they had no more bullets to fire. They emptied their weapons, blazing so hot that Bryan melted his gun barrels.

“It bothered him what happened to those men they couldn’t save,” Wagner said, though hundreds more would have died had Bryan, Halton and the two other American pilots not taken out the artillery.

“Don didn’t talk about taking down five aircraft in one day. He didn’t talk about downing the German jet,” Wagner said. “He talked about the day he destroyed that artillery battery and kept more paratroopers from dying.”