Remembering Suwannee: Tragedy stressed diver safety to Sheck Exley

Published 11:00 am Monday, January 7, 2019

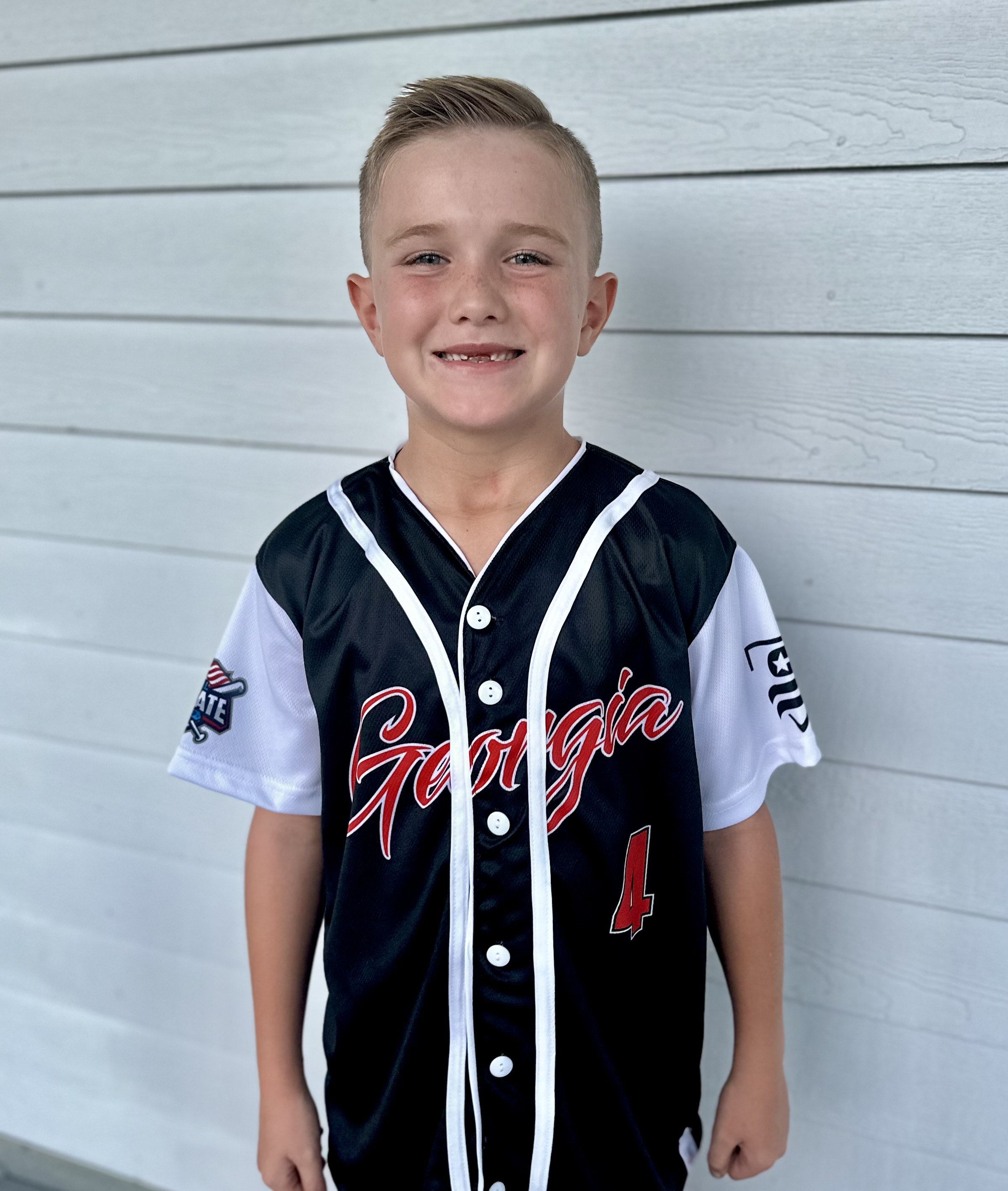

- Sheck Exley as a high school senior.

In discussing Telford Springs, I briefly mentioned diver Sheck Exley. However, I realized that despite him being internationally known, I had never written an article on him (although I have discussed him in various historical presentations over the years). Today’s article will rectify that.

Irby Sheck Exley, Jr. was born on April 1, 1949, to Irby and Virginia Exley of Jacksonville, where his father was a long-time owner of Westside Volkswagen and active in civic affairs. Sheck began diving in 1965 while still a teenager, and quickly discovered a love of cave diving that remained with him the rest of his life. He also took up karate, which some suggest helped him mentally and physically with his diving career. Exley attended Robert E. Lee High School in Jacksonville at the same time as band members of Lynyrd Skynyrd, as well as the band’s namesake Coach Leonard Skinner. Exley was involved in baseball, football, Spanish Club, and Student Council, among other interests at the school. After graduating, Sheck attended the University of Georgia (his father’s alma mater), but would often come home on weekends to dive using his purchased equipment. Sheck would tinker with the diving equipment, going so far as to find and correct flaws in SCUBA regulators designed by Navy engineers.

Trending

On June 29, 1968, Sheck (home from college) and his 15-year-old brother Edward were free diving in Wakulla Springs, each one trying to outdo the other in how deep they could go with Sheck’s new depth gauge. They took turns; first 30 feet, then 35, then 42, then 50. Edward dove deeper than either had gone and began to ascend, but then went limp and floated downward. Three times, Sheck tried to free dive to rescue his brother, but Edward was just too deep. Sheck returned to his car and grabbed his SCUBA gear, but was too exhausted to strap it on and continue. A nearby diver grabbed the gear and retrieved Edward from the bottom of the spring. Sheck resuscitated Edward enough for him to be transported by ambulance to the hospital; however, he did not regain consciousness and died later that night. The loss of his brother stressed to Sheck the importance of diver safety, which he would push his entire career.

Exley continued his diving career and established dozens of diving records. Among the records that still stand 25 years after his death, he was the first person to reach 1,000 cave dives, made the longest solo cave penetration dive ever recorded (10,444 feet in the Chip’s Hole Cave System between Tallahassee and Crawfordville), and was the first SCUBA diver to go below 800 feet (and one of only 11 men in history to have done so in total). Many of Exley’s records were made possible by his unusual resistance to nitrogen narcosis, which allowed him to continue when other divers would have passed out or quit. In 1971, Sheck was the safety diver for Archie Forfar and Anne Gunderson, two divers trying to set a compressed air-only depth record. When the divers got into trouble far below him, Sheck descended far below the safety depth of 300 feet to help them. However, at 465 feet he began experiencing nitrogen narcosis and blackout. Realizing that he could go no deeper without passing out, Sheck returned to the surface; Forfar and Gunderson perished. As a result, Sheck unintentionally became the record holder for compressed air-only dives, a record which will probably continue to stand as such hazardous attempts are no longer recorded.

More on Sheck Exley next week.

Eric Musgrove can be reached at ericm@suwgov.org or 386-362-0564.