Weird Valdosta: Skunk apes, doomed poets, UFOs part of Valdosta legacy

Published 2:00 pm Saturday, April 27, 2019

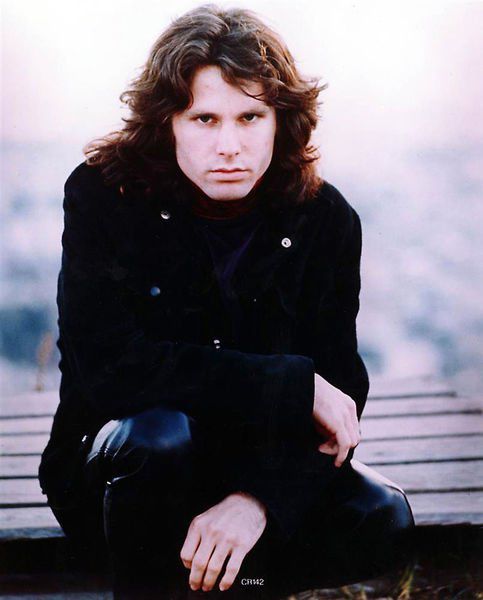

- Did Jim Morrison of The Doors ever live in Valdosta? Write poetry in Sunset Hill Cemetery? That’s the legend.

VALDOSTA — South Georgia is home to several fascinating and fantastic tales.

Here are just a few stories that make up “Weird Valdosta.”

Babylon Valdosta

Valdosta State University has possessed several small tablets from ancient Babylon.

The 10 tablets are approximately one and half inches square. They are made of clay and come from the ancient Babylon/Mesopotamia region of the Middle East.

Ages of the tablets range from 2300 B.C. to 500 B.C. Eight are in excellent condition, with markings visible, while two are in poor and crumbling conditions, with few discernible markings.

The tablets in fine condition are the oldest and are believed to be from the Ur III period, circa 2112-2004 B.C. The two disintegrating tablets are believed to be from the time of Hammurapi and the neo-Babylonian respectively.

The markings are cuneiform, a writing form used by the Babylonians and Assyrians, and are carved into the clay of pre-baked tablets.

How did VSU come into possession of these tablets?

Meet Edgar J. Banks.

In 1920, Dr. Richard Holmes Powell, first president of South Georgia State Normal College, which became VSU, and for whom Powell Hall is named, purchased the tablets for about $40, according the VSU Archives website.

“Local legend has it that Powell purchased or arranged for the purchase of the tablets while he was on leave from the college serving abroad in the Red Cross in 1918 (during World War I),” according to Dr. Melanie Byrd, a VSU history professor, on the university website.

There is, however, no conclusive evidence that Powell’s Red Cross service was overseas or that it brought him into contact with the tablets’ seller, Edgar J. Banks.

Banks was a turn-of-the-century archaeologist and antiques dealer with numerous adventures in the vein of Indiana Jones.

Unlike the fictional Jones, Banks is regarded as less than heroic in his pursuits. The word “infamous” is as likely to accompany his name as the word “famous.”

Banks was a breed of archaeologist scouring the remnants of ancient civilizations at a time when American populations wanted a touch of the Holy Land but many European nations wanted confirmation of empire, Byrd said in a past interview.

Unearthing relics of past empires and claiming them as the possessions of current empire-builders was the vogue of early 20th century state-sponsored archaeology.

As presumptuous as this may sound to modern sensibilities, Banks was reportedly viewed as a rogue even within this system. His dealings reportedly led authorities to kick him out of what is now Iraq.

In 1900, though, “Banks applied for and eventually received permission from Ottoman (Empire) authorities to dig in the modern-day city of Bismya, Iraq, site of the ancient city of Adab,” according to the VSU website. “It is likely that the tablets similar to the ones owned by VSU were acquired from this area; however, he also purchased tablets from workers at other sites.”

“He imported at least 11,000 such relics to the United States,” according to Banks biographer Ewa Wasilewski, “and some estimates suggest the number may have been as many as 175,000 pieces.”

VSU is one of several universities, colleges and museums across the United States owning pieces purchased from Banks.

Judgment for Valdosta?

In 1865, shortly after the end of the Civil War, Valdosta fell into the shadow of an unexpected total eclipse. Reports of the time claimed many Valdosta residents believed the sudden loss of daylight meant Judgment Day had come. They were relieved when it passed without passing judgment.

Promise kept

Geraldine McLeod Clifton and Dorothy Peterson Neisen’s book, “Church and Family Cemeteries in Lowndes County, Georgia 1825-2005,” details the story of Mary Sandwich. She was the teacher of a school in Olympia, a small sawmill town south of Clyattville.

“She was fond of high-spirited horses and rode one to school every day,” the book notes. “She was told by her friends that a horse would one day kill her.”

She told them that if riding a horse led to her death then her friends should bury her on the spot where she fell. Mary Sandwich died riding a horse. Her request was remembered and honored.

Mary Sandwich is buried where she fell.

No Room In Valdosta

Famed for writing the poem “Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight,” American poet Vachel Lindsay rose to early 20th century fame by going on a series of walks across America.

“He took no money with him. Instead, at farmhouses and small villages along the way (he left the cities alone), he traded his poetry for food and shelter,” according to the Vachel Lindsay Association.

On his walks, which he called “tramps,” Lindsay kept a simple set of rules.

“I was to begin to ask for dinner about a quarter of 11 and for supper, lodging and breakfast about a quarter of five. I was to be neat, truthful, civil and on the square,” he wrote. “I was to preach the Gospel of Beauty … I always walked penniless. My baggage was practically nil.”

Reportedly, Valdosta was the only place that did not extend him a hospitable welcome.

Leaving Jacksonville, Fla., he gave a show in Cranford, stayed with a preacher’s family, visited a church, before setting his sights on Macon as the goal for his next major stop, according to one Lindsay biography.

He purchased a train ticket which took him as far as Fargo, where it was the literal end of the line for one set of tracks as well as the end of the line for Lindsay’s money.

In Fargo, he talked his way into a caboose ride to Valdosta as he continued working his way toward Macon. Lindsay had been told he might be able to convince a train official in Valdosta to give him another train ride to Macon.

In the caboose, biographer Edgar Lee Masters writes, Lindsay was so swept up by excitement for his adventure that he repeatedly exclaimed, “By Jove!” One railroad official warned Lindsay to quit with the “By Joves!” or he’d have him tossed from the caboose. The railroad man explained he was religious and he didn’t appreciate Lindsay’s swearing.

Lindsay reached Valdosta, where he gave the railroad’s general superintendent a letter from the YMCA and explained his mission. The superintendent was unimpressed and refused to give Lindsay a free ride. Reading a poem wouldn’t get Lindsay a ticket either.

While at the Valdosta train stop, Lindsay befriended a drunk Texan and soon had the 10 cents to board the train.

The refusal by the train superintendent could have been the basis for the impression that Valdosta was inhospitable to Lindsay, according to the Vachel Lindsay Association, which noted there is no hard evidence that Valdosta was the only place that did not extend kindness to Lindsay.

Still, the incident led playwrights Joseph Robinette and Thomas Tierney to include Valdosta’s refusal as one of the songs in their 1970s musical on Lindsay’s life, “Trumpet of the New Moon.”

Here is the end of that song:

Vachel: Is anybody home? Is anybody home? At any number anywhere, Valdosta way — any number anywhere Valdosta, G.-A.?

All: What can we do for you? What can we do for you? Anything you ask us we will do. Anything you ask us we will kindly do.

Vachel: I need a little love — a cheerful word. “Oh, I’m very sorry” is all I’ve heard.

All: Oh, we’re so very sorry, what can we say? We’re awfully careful with our love, because it might get away.

Vachel (speaking): But that’s how love grows. You’re supposed to give it away!

All (speaking): Not in Valdosta, G.-A.!

Vachel: Is anybody home?

Coincidentally, Tierney and Robinette are friends of VSU Theatre’s Randy and Jacque Wheeler and were commissioned to write a youth musical for the opening season of Peach State Summer Theatre.

Robinette and Tierney found a far more welcoming greeting than Vachel Lindsay did from Valdosta when attending the opening night of their youth play in Valdosta.

Valdosta’s Lizard King

The late rocker Jim Morrison of the band The Doors, who is often referred to as “the Lizard King,” has some connection with Valdosta, though no one seems exactly certain what it might be.

Some legends have placed Morrison in Valdosta, for a brief time during his youth. Legend claims he wrote poetry in Sunset Hill Cemetery, but there is no known evidence to support these claims.

The Morrison biography “No One Here Gets Out Alive,” by Danny Sugerman and Jerry Hopkins, lists Valdosta as a locale for the authors’ research, though Valdosta is not mentioned in the book’s text. Occasional attempts to interview the authors have been fruitless through the years.

Valdosta vs. ‘God’

In the early 1900s, the black evangelist who became famous in the later 20th century as Father Divine preached throughout Georgia and set up a ministry in Valdosta in late 1913, according to past information released by the Lowndes County Historical Society.

During this period, Father Divine claimed to be God.

He gained a strong following among women, teaching “celibacy and the rejection of gender categorizations, which was liberating doctrine for Southern black women.” The men, however, “were not amused.”

At the urging of followers’ husbands and area preachers, Valdosta arrested “God” in February 1914 on charges of lunacy. That, by the way, is how the arrest report reads that “God” was arrested.

“God’s” influence extended outside of just the black community. He also found followers in Valdosta’s white community.

“One white follower, J.R. Moseley, arranged for J.B. Copeland, a respected Valdosta lawyer, to represent him pro bono.” “God” was “found mentally sound in spite of ‘maniacal’ beliefs.'”

Nonetheless, outraged husbands ran him out of Valdosta.

From there, “God” moved to New York where he started a new mission with many of the same tenets. He eventually took the name of the Rev. Major Jealous Divine.

He grew a massive following through the years, attained a great amount of wealth, and much influence. He passed away at the estimated age of 85 in 1965.

UFO: Valdosta

Moody Air Force Base pilots have reported seeing UFOs on several occasions through the years.

In his first “Weird Georgia” book, Jim Miles details several instances where Moody pilots could not identify what they have seen.

There is a 1953 occasion as well as instances in 1973, 1978 and 1952. The book lists several other occasions when UFOs and other unexplained phenomenon were sited by others in Valdosta.

With an Air Force base nearby, one might expect residents to occasionally glimpse something that they do not recognize but for Air Force pilots to witness strange aircraft, that’s something altogether unexpected.

Meet the Skunk Ape

Few stories seem to have piqued reader interest more than the Skunk Ape stories published about a decade ago in The Valdosta Daily Times.

The stories about the Bigfoot-type creature resonated with both the child within all of us but particularly with children. Readers noted their young sons taped copies of the Skunk Ape front page to their bedroom walls. One reader scolded The Times for scaring her young daughter.

But The Times story developed from a reader asking if we’d seen Brooks County connected with the Skunk Ape on various national Internet websites. A quick search of the Internet revealed that many websites claimed the most recent sightings had been reported in South Georgia.

Visit Skunk Ape websites and they listed in great detail sightings of the creature.

Sites detailed a Clinch County sighting, a 2008 Berrien County case, a Valdosta resident reporting a sighting from the 1950s. The Times story prompted readers to call in sightings locally.

Again, The Times story was prompted by several websites, from the Chicago Tribune to the Florida Sun Sentinel, including this same passage: “In recent months, several sightings have been reported near the Withlacoochee River in Brooks County, Ga., between Quitman and Valdosta.”

Brooks County officials said at the time such reports were news to them. The origin of these initial reports seemed as uncertain as the Skunk Ape itself. The Skunk Ape has been known by many names: Swamp Logger. Stink Ape. Swamp Monkey. Florida’s Bigfoot.

The Skunk Ape is a hominid, walking on two legs similar to a man, but it also reportedly lives among trees like a monkey.

Its foul odor, often described as the reek of rotten eggs or hydrogen sulfide, puts the “skunk” into the creature’s name. A Skunk Ape witness said in 1977: “It stunk awful, like a dog that hasn’t been bathed in a year and suddenly gets rained on.”

The Skunk Ape has been described as being about six-and-a-half to seven feet tall. A build that is shorter and weighing far less than the descriptions of the eight-foot, 1,000-pound Bigfoot. Like Bigfoot, a Skunk Ape has never been caught and sightings are often regarded with skepticism.

Yet, Skunk Ape sightings reach back hundreds of years. Florida’s Native Americans reportedly called the creature “Shaawanoki.”