‘This is life and death’: lawmakers, health leaders take on maternal mortality

Published 8:30 am Sunday, December 1, 2019

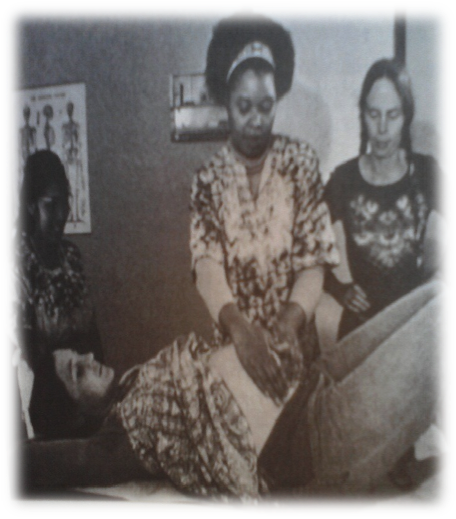

- This photo of Umm Salaamah Abdullah-Zaimah on a midwifery training farm in Tennessee is from the 1976 book 'Spiritual Midwifery' published by Book Publishing Company.

ATLANTA — When just a teenager, Safira Z Yasin said she “died on the table” during the birth of her first child in 1993. After being resuscitated, she woke up with a tube down her throat and her baby missing.

Yasin was kept from her baby for seven days.

“My doctor told me I was ready to have my baby when he was ready,” she said.

She said the doctor seemed to care more about his schedule than delivering her baby to her.

Similar traumatic birth experiences and maternal deaths have shaken Georgia women and their families — especially in communities of color.

In 2014, the national rate of maternal mortality was 17 deaths per 100,000 live births. In Georgia that same year, the rate was 25.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Aligning with national statistics, white and non-Hispanic women saw 14.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, while black and Hispanic mothers saw more than triple that rate.

Almost six years later, the state is still reaching for answers.

While lawmakers question the validity of the data and collection process — researchers, doctors, midwives and advocacy organizations grapple with what they can do to save women.

Georgia’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee — established in 2013 — has a lengthy process of reviewing potential pregnancy caused deaths, determining the actual cause and analyzing the data. From 2012-14, the committee reviewed 250 possible cases of maternal mortality and found 101 were directly related to pregnancy.

The main causes of pregnancy-related deaths were hemorrhage and hypertension. About 60% of the maternal deaths reviewed by the committee, or 62 women, were deemed preventable.

Pre and post-natal care deserts

The Mercer University School of Medicine’s Center for Rural Health and Health Disparities is among the higher education institutions working to combat maternal mortality in Georgia — specifically in rural areas.

According Dr. Jacob Warren, director of the center, rural African-American women have 30% maternal mortality than urban African-American women while rural white women have 50% higher risk than urban white women.

“There are layers of risk for rural women in particular,” Warren said during a presentation to the House study committee on Oct. 17.

The lack of access to health care in rural Georgia is extreme, he said, 93 rural counties have no hospital with a labor and delivery service and two thirds of rural births happen outside of the mother’s home county.

Women in rural areas face increased burdens in many ways, including transportation to care, less support organizations and less government service locations.

But the biggest challenge rural mothers face is the high rates of hospital and birthing unit closures across Georgia. Georgia is among a group of states with high rates of rural hospital closures — behind Texas and Tennessee — some argue largely due to the states’ refusal of Medicaid expansion.

According to a briefing in July, Deloitte consultants — hired by the state to help draft health-care waiver proposals — seven rural Georgia hospitals have closed since 2010 and 26 facilities are at risk of closure.

Warren said 43% of rural labor and delivery units have closed in the past 20 years — leading to obstetricians leaving to urban areas for work.

“It’s a cascading affect in rural Georgia when you have a labor and delivery unit close,” Warren said, “it affects the entire continuum of care.”

Professors from the Medical School of Georgia at Augusta University testified to lawmakers that rural physicians are aging and becoming fewer.

Jimmy Lewis, chief executive officer of Hometown Heath, founded the network organization of about 50 rural hospitals and health-care providers more than two decades ago. Lewis has seen first-hand the difficulty of keeping rural hospitals and labor units afloat.

The lifespan of a rural hospital is based entirely on financial stability, Lewis told CNHI. The downward migration of deliveries — for various reasons such as rural populations aging and prevalence of poverty — has forced many hospitals and health -care providers to close.

The problem has spread care options miles apart. From Augusta through Milledgeville into South Georgia, Lewis said, deliveries are “few and far between.”

“Simple fact of the matter, a closure consideration ends up being a financial decision,” he said. “Georgia has had its major challenges with infant and maternal mortality simply because you have so far to travel and when you have to travel so far, the prenatal and postnatal care goes lacking.”

Lewis said it takes about 350 deliveries per year for a hospital to break even in labor unit costs. Rural hospitals in the Hometown Health network are often seeing only 150 to 180 per year, racking up hundreds of thousands in debt.

Giving up a labor unit is a “traumatic experience” for both hospitals and the communities they serve, Lewis said.

“The people have lived in a community where babies were always delivered,” he said. “It’s a wake-up call to the community and it’s a shake up to the community to understand they have to give that up.”

Rural health-care providers are attempting to extend their scope of services in any way they can, he said, utilizing telemedicine to cover the miles between doctor and patient.

But at the end of the day, Lewis said, Georgia is coming up short — short on doctors, nurse practitioners, physicians assistants, let alone obstetricians.

‘Boots on the ground’

Many midwives went into birth work after traumatic birthing experiences such as Yasin’s and they’re making the case to spread their ways to rural women in Georgia.

Umm Salaamah Abdullah-Zaimah, 76, has lived many lives. She was among the first class of New York City women police officers to be allowed to patrol the streets. Later, she became the first black graduate of Emory University’s midwifery masters program — but she didn’t get there by design.

Abdullah-Zaimah suffered a traumatic birth at the age of 18 at a naval hospital in 1961. Doctors performed two large incisions that split her from front to back and used forceps to take out her baby.

She buried the memories for years, but when her teenage daughter and goddaughter became pregnant, she wanted to save them from the possibility of that experience.

“I didn’t want to see her get turned off to having children. I thought, there’s got to be another way,” she said. “How can I save her from all that?”

She cared for them — unable to find available midwives — and both babies were born healthy. But the third baby she “caught” gave her a glimpse of how pregnancy can go very wrong. The baby had a knot in the umbilical chord and came out still. The trained midwives on their way rushed in the room just in time and resuscitated the newborn.

“That’s when I realized, this is not something you learn from a book, this is life and death,” Abdullah-Zaimah said. “And if something happens to somebody that could have been prevented, could you live with that?”

She dedicated the rest of her life to midwifery. Abdullah-Zaimah went and studied the profession on The Farm, a midwifery training location in Tennessee. There, she learned being a midwife meant also being a teammate to the mother.

That is what makes midwives stand out from traditional medical models, Abdullah-Zaimah said.

Since, she’s worked in 10 states and four countries — delivering thousands of babies. She is an elder midwife and current co-chair of the Community Midwives National Alliance based in Atlanta.

Georgia’s high rates of maternal mortality get even higher the farther away from metro areas. Midwives are making the case that health-care systems need to take more advantage of birth workers already in rural communities who can guide women through “low-risk” births.

We already have one of the most advanced health-care systems in the world, but we have the worst maternal mortality statistics out of all industrialized countries — even lower than some “war-torn” countries, Abdullah-Zaimah said. Technology advances aren’t always the answer.

“What we need here in this country, we need boots on the ground,” she said. “We need women who are already there, who live in the area, people already know them, they already trust them, people already go to them and ask them for advice. Those are the people we need to train, to give them the skills necessary to recognize problems and to do the normal deliveries where the people are, where they live.”

People have lost sight of what midwives are, Nasrah Smith, elder midwife and co-chair of the midwife alliance, said.

Midwives, medically trained birth workers and doulas, their counterparts who provide other supports, are with mothers from conception to post-pregnancy. They’re the “hand-holders,” they teach them to listen to their body, eat a proper diet, Smith said, and most importantly to keep up with their mental health throughout the pregnancy.

Midwives offer other unique services tailored to a family based on their needs. The goal, she said, is to make sure there’s better birth outcomes for the mother, baby and family.

Jennifer Barkin, associate professor of community medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, at the Mercer School of Medicine, said that about 25% of women suffer from postpartum depression and nearly the same amount suffer from perinatal anxiety.

This can bleed into family dynamics, she told the House study committee on Nov. 21, causing fathers to have mental health issues as well.

Midwives sometimes face scrutiny from the medical community. But ultimately, Smith said, all birth workers have a role in addressing maternal mortality in Georgia.

“Even though opposition is there, we don’t deal with opposition,” Smith said, “We’re focused on a crisis. We’re focused on something that we’re really concerned about. … We’re dealing with a very serious issue that needs to be addressed and it’s more black moms than white moms.”

Black mothers at higher risk

“It’s not easy being black in white America,” Abdullah-Zaimah said.

Black women face hundreds of small stressors daily and often have their concerns dismissed by doctors, she said.

“A lot of times people just don’t understand what people’s lives are like,” she said. “And if that happens to you once, you might never go back. … And the thing is in the black community, it doesn’t really make any difference how much education you have, how much money you make.”

Abdullah-Zaimah referenced two high-profile, Atlanta mothers who died during child birth. Shalon Irving, a Center for Disease Control epidemiologist and lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, died from complications during child birth in 2017. Kira Dixon Johnson, who died during child birth in 2016, spoke five languages and was the daughter-in-law of well-known Glenda Hatchett, star of the reality court TV show “Judge Hatchett.”

When a mother dies — it usually leaves a child in the hands of someone who didn’t expect to care for a baby. A father is now a single parent, grandparents are raising another young child or the child is added to the nearly 14,000 kids in Georgia’s foster-care system.

“If the mother dies, the chances of the child surviving go down,” Abdullah-Zaimah said. “Any child she has who is under 5 years old is at risk if she dies.”

Representation among birth workers is key, she said, expecting mothers want help from people who look like them. But combatting maternal mortality means bringing training to women in rural areas to spot the warning signs for when a mother needs to go to the hospital.

Georgia midwives are pushing the state legislature for licensing and regulation of “community midwives.” The legislation would create a certified community midwife board, appointed by the governor, that would oversee licensing and certification.

Through the bill, community midwives will handle “low-risk” pregnancies and labors that are not induced with medication and the infant is born within a regular time period. If there are signs of any abnormalities, midwives would recommend medical attention immediately. But not everyone is a candidate for home birth, Smith said.

Dr. Jacob Warren from the Mercer’s Center for Rural Health and Health Disparities outlined a need for pre- and post-natal “case management” in rural areas that would include risk-based services, regular check-ins and home visits – similar to what a community midwife would provide.

Midwives and traditional medical health-care providers have to work together, Smith said.

“These efforts need to be inclusive,” Smith said. “This is a big giant, we have to take a bite at a time. We need to come to a common ground.”

Yasin, a student midwife and certified doula, does birth advocacy and is the secretary for the midwife alliance. She is working for bipartisan support of the bill.

The midwife alliance doesn’t have money to lobby its cause, she said, but it has the experience of birthing thousands of babies. Between all the elder members of the group, there are maybe 20,000 birthing experiences between them.

“(Lawmakers) are not blind to what’s going on,” Yasin said.

The ones who survived

Chris Tice said the stories of Georgia’s women who died because of pregnancy follow her home from work.

Tice is the lead abstractor and review coordinator for the maternal mortality review committee and has spent more than two years reviewing cases of Georgia mothers who have died after child birth.

“I feel personal with these women. I try to give them my full attention and I pray over them,” Tice told CNHI. “That’s what I wish people would know, that we’re not just crunching numbers. I take these these women home with me. And I’m trying to give them a voice.”

Tice dives into the mother’s life — pouring through medical records, records of prenatal care, records of transportation to and from doctors, psychiatric care records, law-enforcement records and coroner reports. She looks for both reports of normal and abnormal care in the mother’s history.

Case abstractors such as Tice need an obstetrics background — Tice is a registered nurse and certified nurse midwife.

In Georgia, abstractors examine all cases of mothers’ deaths up to 365 days post-pregnancy. One case study takes an average of 20 hours to review after all the requested records are received.

The maternal mortality review committee was appropriated $200,000 in last year’s budget, Tice said, but additional funding for more abstractors and epidemiologists would help the committee catch up to current statistics. The 2015 case review findings will be available to the public by January.

Women who died by homicide, suicide or overdose within the year period after pregnancy are also reviewed, Tice said, a practice that began in 2014 to see if domestic violence and the opioid epidemic are affecting Georgia’s maternal mortality rates.

But women who died aren’t the only ones health-care professionals need to review, she said. It is important to review not only why women are dying, but why women come close.

Valerie Montgomery Rice, the president and dean of the Morehouse School of Medicine, said their research will extend to case review of “near misses” — women who almost died from pregnancy. Morehouse research will also look at delays in receiving health care including why women wait or refuse to receive care.

“Dead women cannot talk, they cannot speak,” Rice said. “We have to hear from the women who survived and understand what we did not do well enough to give them the confidence to come in sooner.”

Long-term solutions

Even just the push for research on maternal mortality is facing its own obstacles.

Funds to go to research on maternal mortality, let alone solutions, is set to be cut as part of Gov. Brian Kemp’s mandated state agency budget cuts. The Morehouse School of Medicine is threatened with losing $500,000 to go toward a specialized center for maternal mortality research.

House committee Co-chair Rep. Sharon Cooper, R-Marietta, told Rice during the Oct. 17 meeting she is actively lobbying the governor’s office to get that money back.

Lawmakers, researchers and birth workers have all agreed on one thing: Medicaid coverage of mother post-pregnancy should be extended from 60 days to 90 days — or even more ideal, a full year after giving birth.

In dismay over the data collection-focus of the first study committee meeting, Rep. Mable Thomas, D-Atlanta, called a press conference of women’s rights leaders to call upon the state for more action.

Denatte Glass, director of the Center for Family and Community Wellness, said part of the solution would be opting for full Medicaid expansion — the idea avoided by Kemp while he proposed his own health waiver initiatives.

“In the state of Georgia, we don’t think it’s a necessity to have Medicaid expansion,” Glass said. “So if we’re going to talk about prenatal access to services, but you’re not allowing women to have those services, we have a challenge.”

The issue of maternal mortality is gaining more ground on the national stage. During their visits to Atlanta for the fifth Democratic presidential debate, multiple candidates called for the state to address its high mortality rates.

State Democrat lawmakers have also linked the state’s abortion ban to maternal mortality.

Rep. Donna McLeod, D-Lawrenceville, said during a press conference criticizing President Donald Trump’s visit to Atlanta, that Republican policies will only worsen the maternal health crisis.

“The Republicans’ extreme agenda threatens to rip reproductive rights in our state by passing Brian Kemp’s abortion ban and the Trump administration attempts to strip federal funds from health-care providers that provide reproductive care,” McLeod said. “Simply said under the Republicans health-care agenda, more women are likely to die.”

Tiffany Crowell, perinatal executive director of Parents as Teachers and program manager of Baby LUV for the Georgia Department of Public Health South Health District, told CNHI educating for family planning plays a crucial role in maternal health.

“If you prepare your body prior to getting pregnant,” she said, “then chances are you’ll have a healthier birth outcome if you manage those issues before you get pregnant.”

Women planning on being mothers should manage their blood pressure and weight before pregnancy, Crowell said.

Colquitt County is an at-risk area for a high number of maternal mortalities and has hight rates of infants born with low birth weights.

The Centering Pregnancy Program provided by the Georgia Farmworker Health Program in Ellenton, Colquitt County and the Dougherty County Health Department, helps mothers manage their pregnancies.

The program brings eight to 10 women together who are all due at the same time to provide care and stability for each other. Program providers monitor the mother’s health throughout stages of pregnancy.

“One of the major things that also contribute to maternal mortality is how the mothers eat; obesity is a big benefactor of maternal mortality,” Cary Welldon, director of Ellenton Clinic, said. “Our major population that we take care of here is Hispanic, and many times they don’t know how to eat. We have a nutritionist come to our Centering classes to show them how to cook healthier meals that provide for both the mother and the baby.”