Georgia pivots to wrongful conviction pay

Published 8:00 am Monday, February 28, 2022

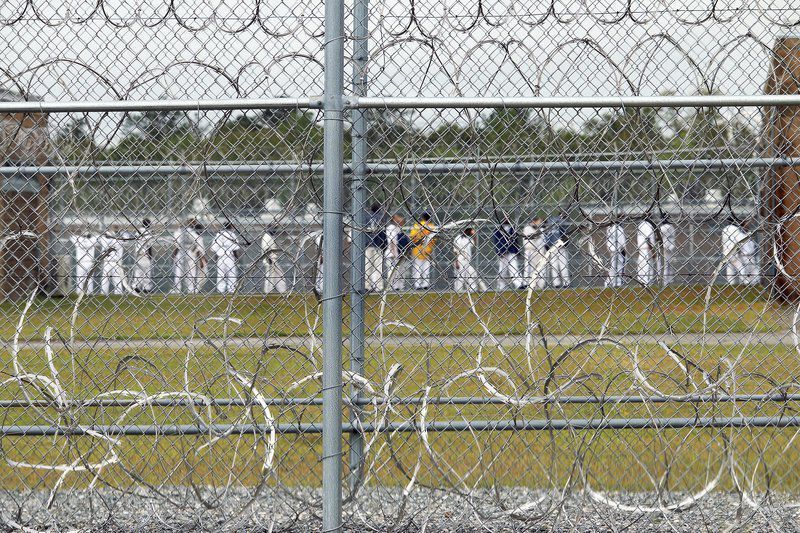

- Georgia’s recidivism rate hovers around 30 percent, meaning three out of every 10 released prisoners relapse into crime within three years, which is the time range most government agencies use to measure recidivism.

ATLANTA — A bill to set standards for compensating people exonerated of a crime in Georgia received unanimous approval from the House Judiciary Non-Civil Smith Subcommittee.

The “Wrongful, Conviction Compensation Act,” House Bill 1354, defines exonerated as having a conviction reversed or vacated; having the indictment or accusation dismissed or nolle process after a retrial; someone acquitted after a retrial; or someone who received a pardon based on innocence.

The committee approved an amendment to the original bill that adds a stipulation that the exonerated cannot have been convicted of any lesser included offenses.

“This is the same standard that you would have applied for record restriction that basically if you’re convicted of the lesser included offense, you’re not entitled to have the greater offense restricted,” said Robert Smith Jr., general counsel for the Prosecuting Attorneys’ Council of Georgia, who assisted in drafting the bill. “While you can say you’re found not guilty of the greater charge, saying that you’re exonerated and entitled to compensation because you’re convicted of a lesser included offense, I don’t think it’s in line with the spirit of the bill.”

Smith said, for example, a person originally convicted of burglary who was later convicted of criminal trespass after a retrial would not be considered “exonerated.”

Currently, someone exonerated of a crime in Georgia can petition a state legislator to sponsor a compensation bill that would have to garner majority approval in the state legislature. Amounts of compensation in the few successful cases have varied greatly through the years.

Proponents of statutory compensation laws say it’s necessary to to help fund housing, food, transportation, medical and counseling services, education and workforce assistance and legal service.

In Georgia’s proposed statutory compensation bill, the exonerated’s pay would be determined by a Wrongful Conviction Review Panel and based on the number of years spent incarcerated. The bill states the panel may recommend $100,000 per year but no less than $50,000 for each year of wrongful incarceration and encourages the board to strive for consistency among claims.

“If the skill level of the individual was quite advanced, (the panel) might want to be closer to the ceiling,” said Rep. Scott Holcomb, the bill’s sponsor. “If the skill level of the individual was maybe less skilled, in terms of employment opportunities, and so they thought the fair basis for the compensation was lower, those would all be types of things that they could take into account.”

The dollar amounts are to be adjusted annually for inflation.

“It helps to solve the problem that we’re attempting to solve which is to keep this from having to continually come back from the legislature,” Holcomb said. “By building it in, it gives some flexibility for just to be increased over time, without maybe a political fight about what the floor and ceiling should be.”

As for the five-member panel’s composition, the chief justice of Georgia’s supreme court would appoint a felony criminal court judge; the governor would appoint both a prosecutor and a criminal defense attorney; and the Speaker of the House and President of the Senate would each appoint either an attorney, forensic science expert or law professor.

The exonerated must submit a claim to the panel within three years of being exonerated. Within six months, or within a year if a hearing was held, of receiving the claim, the panel would prepare a written recommendation to the state claims board, which must then adopt the panel’s recommendation to submit to the Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice. The Chief Justice would then include the recommendation in the upcoming judiciary budget year, if received before Sept. 1. The compensation would come out of the following year’s budget if received after Sept. 1.

Georgia’s proposal was approved unanimously by the Republican-dominated House judicial committee and awaits approval in both the House and Senate.

According to the Innocence Project — a nonprofit that works to exonerate the wrongly convicted through DNA testing and end wrongful conviction, Georgia is among 13 states that do not have statutes in place for compensating people wrongly convicted. The states include Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Kentucky, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and South Dakota.

“It would be really great for Georgia to have something that’s in place that citizens can count on for these circumstances,” said Jill Travis, executive director of Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

A study from the National Registry of Exonerations found that Black people are more likely to be wrongfully convicted of a crime, stating that while Black people make up only 13% of the U.S., they constituted 47% of the 1,900 exonerations listed in the National Registry of Exonerations as of October 2016.

Of the nearly 3,000 exonerations that have occurred in the country since 1989, 61% were due to perjury or false accusation, and 56% involved official misconduct from police or prosecutors, according to National Registry of Exonerations.

Texas (400), Illinois (385), New York (331) and California (274) lead in the highest number of exonerations.

Other state exonerations since 1989, according to National Registry of Exonerations data:

Georgia: 47 exonerations, 538 years lost, 11.45 average years lost.

Alabama: 28 exonerations, 204 years lost, 7.3 average years lost.

Mississippi: 25 exonerations, 319 years lost, 12.75 average years lost.

Tennessee: 35 exonerations, 326 total years lost, 9.33 average years lost.