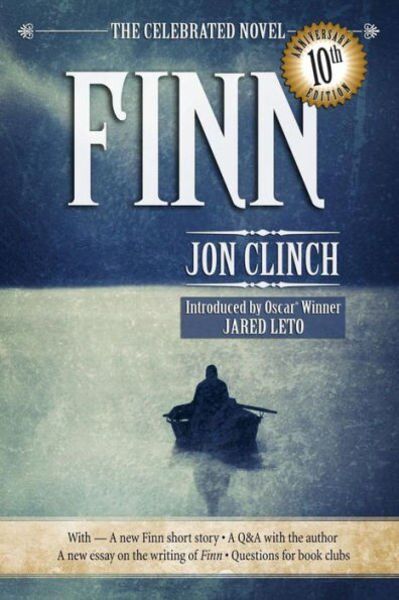

BOOKS: Finn: Jon Clinch

Published 11:00 am Saturday, November 21, 2020

- Finn

Part of the genius of Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is that he confronts the stain of American bigotry through the leavening eyes of the mischievous youngster Huck Finn.

Twain doesn’t skirt the issues of America’s struggles with race, but he makes his points subtly. Like a master illusionist, Twain keeps readers busy with his yarn’s humor in one hand while he quickly reveals a powerful message with the other. This fine balancing act is part of what made “Huckleberry Finn” a best-seller in its time.

Twain’s novel became an enduring American classic with its combination of humor, tragedy and revelation into matters of race running throughout U.S. history as deep and wide as the Mississippi River.

Jon Clinch dares cast his writing skiff onto the famed waters of Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn” with a powerful debut novel from several years ago called simply “Finn.” A book worth visiting again.

Clinch’s book casts as its protagonist Huck’s Pap, the brutal father whose shadow lingers on the outskirts of Twain’s adventure while sporadically tormenting young Huck.

Huck’s Pap is one of American literature’s least known characters yet one of its best-known scoundrels. Clinch fleshes out Huck’s Pap, and it’s not pretty. He is never christened with a first name. To readers, he is just Finn, the disowned son of the prominent Judge Finn, gone to seed trading fish from his hooks for the whiskey that has its hooks in him.

This is the tale of Pap’s life on the Mississippi, and Clinch takes readers on a deep, perilous journey both into the murky soul of Finn and into the race issues that have long haunted the American spirit. Like Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn,” Clinch’s “Finn” is an examination of 19th century American race issues as much as it is a page-turning tale.

In entering the world of Twain’s Mississippi River, Clinch knows he has embarked on the holy waters of American literature. He respects these waters by keeping true to Twain’s encounters between Huck and Pap, but Clinch also dares to splash and swirl Twain’s world into something different.

Huckleberry, for example, has always sounded more like an author’s attention-grabbing device rather than an actual name for a child; Clinch, however, provides a fairly believable character rationale for naming this child Huckleberry.

The biggest difference between the two books is in their respective tones. Both books are filled with racial epithets, more to demonstrate the racism and language of the era and the characters rather than any bigotry by the authors.

Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn” offered a promise of improved relations between the races as demonstrated by the friendship between Huck and Jim. Twain used ample portions of humor to reveal a nation’s bigotry and the promise for something better. There is no humor in Clinch’s “Finn.” It is a moving read but a grim passage along the deep currents of a nation’s soul.