Crossing the food desert

Published 3:00 am Sunday, February 16, 2020

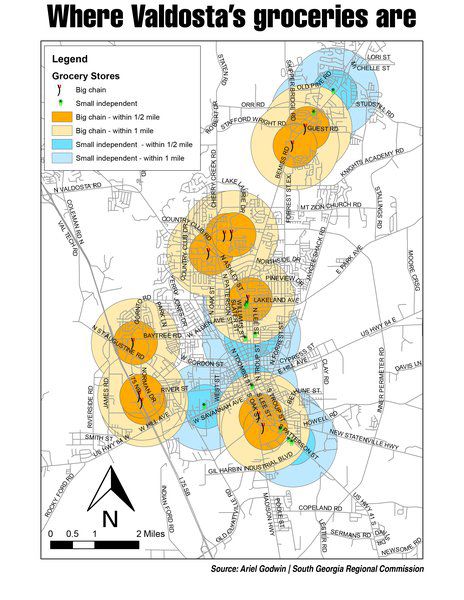

- Contributed map

VALDOSTA — During a city council meeting in late 2019, two ladies stood up during the “citizens to be heard” portion to complain about how hard it was to do any grocery shopping in Valdosta’s south side.

They complained about the lack of supermarkets and how far they had to go to get quality food, sometimes having to rely on convenience stores to stock their larders.

Then-Mayor John Gayle told the ladies he sympathized with them, but “we can’t force businesses to open.”

Data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows much of area in and around Valdosta to be a “food desert” — an area with insufficient access to grocery stores and fresh produce.

The SunLight Project team is took a statewide look at the problems of access to healthy foods and what can be done to improve the situation.

Where are the deserts?

The USDA generally defines a food desert as an urban area in which customers have to walk more than a mile to find a supermarket or a rural area where a supermarket is more than a 10-mile drive away,

In Valdosta, about half of the city qualifies as a food desert, according to federal data. A map from the USDA shows that the “desert” covers all of Valdosta south of U.S. 84 and a large swath of the city’s east side — right over some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. The most recent data from the USDA dates from 2015.

For many years, Valdosta’s only full-sized supermarket south of U.S. 84, which bisects the city east-west, was a Winn-Dixie on the Madison Highway. In 2018, it suddenly closed, part of a court-ordered move by a parent company in bankruptcy.

This left southern Valdosta with no full-sized supermarket for a year before the building was purchased and reopened as a Piggly Wiggly.

Likewise, the closing of a supermarket location in the Castle Park shopping center earlier that year left much of eastern Valdosta without access to a full-sized grocery option until it was later reopened, again as a Piggly Wiggly.

In both cases, there were some choices left in the form of convenience stores and smaller grocery stores — Save-a-Lot on the Madison Highway for the city’s south side and Mr. B’s IGA on Lee Street for the area near Castle Park — but the USDA’s “food desert” system only takes into account large supermarkets.

Two major determining factors in food deserts are income and whether someone has access to a vehicle, said Dr. Anne Price, coordinator for the sociology master’s program at Valdosta State University.

In Valdosta’s low-income areas “many individuals are basically stranded,” she said. Price mentioned one man on Ponderosa Drive who walks by foot to Mr. B’s IGA several blocks away 10 times a month because he can’t carry many groceries by hand.

She said a lack of economic incentives, such as tax breaks or deals on buying land, hampers luring supermarkets into low-income neighborhoods, as well as crime fears.

“It’s not considered the best economic investment to locate there” due to economic reasons, so people who buy more expensive food go elsewhere, Price said.

Areas of Valdosta she regards as underserved include the area around Gordon Street and the S.L. Mason school, as well as student-packed areas of Baytree Road and even historic older areas around VSU and downtown.

In Thomasville, Cheryl Presha has lived in a food desert for two decades.

Although she has transportation to travel to grocery stores elsewhere in the city, there are none in the area where she lives on South Martin Luther King Drive.

“The nearest place would be Smith Avenue,” Presha said.

A full-scale grocery store on West Jackson Street moved to Smith Avenue. A supermarket in the so-called food desert on West Jackson closed a number of years ago.

Tifton has its food problems as well. “Communities on the other side of the interstate are hugely affected when you go past Kelltown because there’s nothing there,” said Vanessa Hayes, Tift County school nutrition director. “There’s nothing there for those families that live on that side. Curtis Packing is on U.S. Highway 41, but you have to cross over three or four streets to get there.”

“And our communities past G.O. Bailey (elementary school). If we look at their area, there’s not an accessible grocery store.”

Moultrie seems to be doing well as far as food access. USDA data for Moultrie shows the city does not have a relatively high number of households (56 of 1,095 total households ,or 5.1%) without vehicles that are more than one-half mile from a supermarket.

The Food Environment Index found on the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps website offered by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute gave Colquitt County a 7.3 rating (0 being the worst and 10 being the best) on healthy food environment.

“I remember when we got our Publix a few years ago, 2016 I believe,” said Moultrie resident Terry Smith. “I was excited personally, because it meant we’d have more options for food. I think we’ve only got a few real grocery stores: Publix and Walmart, Oxley’s and a Piggly Wiggly. And it was nice to have one that was kind of, you know, upscale.”

“I don’t think we’re a food desert, at least not in Moultrie,” said Sarah Todd. “We’ve got quite a few stores and fast food places. I think it’s just a matter of people being able to get to them. Like, my grandma doesn’t have a car, so we bring groceries to her or we’ll take her shopping with us. Some people just don’t have a way to get there.”

What kind of food is available?

Even in the most remote rural areas of Whitfield County, there’s usually a variety store nearby. These stores sell the usual chips and soft drinks, but they also sell milk, eggs, grits and oatmeal and frozen vegetables among other healthy choices.

Michael Webster, of Valdosta State University’s School of Health Sciences, said food can be divided into two groups — “energy-dense,” with lots of calories, much of it fat, but few nutrients, and “nutrient-dense.” Shopping at convenience stores involves lots of energy-dense foods, he said.

Healthier options, such as leafy greens, apples, oranges not often found in convenience stores, Webster said.

Frozen vegetables are particularly healthy, said Ashley Broadrick, a registered dietitian and wellness manager for the Hamilton Health Care System in Whitfield County.

“As a general rule, frozen produce tends to win top rank when it comes to highest nutrition value because it is frozen within hours of harvest. This captures nutrition at its peak,” she said. “Fresh produce must go through harvesting, processing and transport before it reaches our grocery stores, which can impact the nutrition value. The exception is fresh produce bought at a farmer’s market or straight from the land where both quality and nutrition are peak. The lowest nutrition value is in our canned produce, which can also be loaded with salt and/or sugar.”

Many discount stores, such as Dollar General and Family Dollar, carry sizable canned good sections. While canned foods have more preservatives and less nutrient value than fresh foods, they can last for long times, while fresh foods last for 3-4 days, Webster said.

“It’s a tradeoff of quality versus longevity,” he said.

Some discount stores are trying to improve their offerings; some Dollar Generals have begun offering refrigerated fruits and vegetables.

A lack of fresh produce can have an impact on health. “With children, it comprises their immune system development,” said Hayes. “It leads to increased diagnoses of heart diseases and childhood obesity … We have children as young as preschoolers on high blood pressure medication.”

Information provided by Ashleigh Childs, University of Georgia Thomas County Extension Family & Consumer Services agent, shows that eating a variety of fruits and vegetables might have protective properties against some chronic diseases and certain types of cancers.

Important sources of nutrients are:

• Potassium — Aids in maintenance of healthy blood pressure.

• Dietary fiber — Helps reduce blood cholesterol levels and might lower risk of heart disease, important for proper bowel function.

• Folate — Helps form red blood cells, important for pregnant women to reduce the risk of neural tube defects, spina bifida and anencephaly during fetal development.

• Vitamin A — Promotes eye and skin healthy, helps protect against infections.

• Vitamin C — Aids in iron absorption, helps keep gums healthy, heals wounds.

What can be done?

“Get people to the food or get food to the people,” Price said. “You can’t separate the food desert problem from lack of public transport. Valdosta would benefit from a bus system.”

Valdosta has no public transit system. During last year’s mayoral campaign, some candidates claimed public transportation would be too expensive or was not wanted by the public.

Lack of public transportation is an immediate cost versus long-term effects battle, Webster said. Preventative care, including access to healthy foods, is less expensive than having to treat medical conditions later, he said.

Other cities have used tax breaks and land price breaks to bring grocery stores to underserved areas, Price said.

In Tifton, a summer feeding program works to make sure kids are getting fed during the summer. Sites are set up around the county where kids can come eat, and there’s a mobile site as well.

The program is a collaboration between many community organizations, Hayes said.

“The program allowed me to see what kids are fighting through,” she said.

Across the region, Second Harvest of South Georgia, a food bank, works to try to get nutritious food into the hands of people who need it, said Eliza McCall, the group’s chief marketing officer.

Working through food purchases and donations, Second Harvest distributed the equivalent of 15 million meals last year, she said.

Second Harvest is an umbrella organization helping many smaller groups across South Georgia, including 30 in Valdosta, to distribute food, McCall said. Of those 30, two-thirds are located in food desert areas, she sad.

While Second Harvest tries to provide many types of food, many of its smaller partner groups do not have sufficient refrigeration to store much fresh produce, she said.

The food bank takes part in programs that collect good leftover food stocks from restaurants and from farmers for distribution, McCall said.

The SunLight Project team members contributing to this report included Stuart Taylor, Eve Copeland-Brechbiel, Patti Dozier, Charles Oliver, Savannah Donald and Terry Richards.

Terry Richards is senior reporter at The Valdosta Daily Times.