Disconnected: Broadband access lags in rural Georgia

Published 4:00 am Sunday, February 3, 2019

- Terry Richards

QUITMAN – Molly Radford signed up for the fastest internet she could get in rural Brooks County, where her family has owned farmland straddling the Georgia-Florida line for more than a century.

But it is by no means fast. The retired educator pays for up to 3 megabits per second, which is well below the 25 megabits per second download speed that is considered broadband quality.

Many of her speed tests have clocked crawling speeds that barely even register. The fastest she has ever seen is an occasional 2 megabits per second.

That means streaming or downloading video is out of the question. But it’s enough to let her log onto social media or check her email, just as long as no one dares send her a photo.

“It’s just hard on everybody,” Radford said “And we look at other areas of our state where they’re paying less and getting a great deal more. It’s just very frustrating.”

Her frustration boiled over last year when it became clear her provider – the only one available – had no plans to upgrade service in the area as promised. When she confronted the carrier, she was told she would lose access to what little service she had, in addition to her phone line, if she cancelled her internet service.

“It’s just unacceptable in this day and age for the people of rural Georgia to not have basic service,” Radford said.

And she’s not unique.

There are more than 3,300 people in Brooks County who lack access to broadband, according to a new state Department of Community Affairs map. That’s more than 1,600 homes and 22 businesses sitting in digital darkness.

Radford has something else in common, though, with many rural Georgians who are living with little to no internet service: They are also customers of not-for-profit electric cooperatives, which have been piping electricity to rural communities nationally since the 1930s.

A proposal to empower these electric co-ops, along with a handful of telephone co-ops, to provide broadband service has once again emerged in the General Assembly as a way to help boost rural broadband. It’s the third such attempt.

A lead proponent of the measure, Rep. Penny Houston, a Republican from Nashville, is pushing the idea this year with a sense of urgency, citing a looming application deadline for $600 million in federal loans and grants for rural broadband.

Enabling the state’s 41 electric co-ops, or electric membership corporations, to enter the broadband game would bolster the state’s case for claiming a share of that money. Mississippi’s governor signed a similar measure into law last week.

“It is very important to address it and get this thing passed so EMCs can apply for some federal money,” Houston said in an interview at her office last week. “We send that money to Washington and we want it coming back, too.”

‘A great disadvantage’

Statewide, at least 626,070 people live without access to broadband service, according to the Federal Communications Commission.

But it’s probably closer to 1.6 million Georgians who lack access to adequate broadband, according to the state Department of Community Affairs, which is in the midst of a statewide mapping project.

The agency’s initial work, which is posted on its website, shows a patchwork of coverage that is particularly thin in parts of middle and South Georgia.

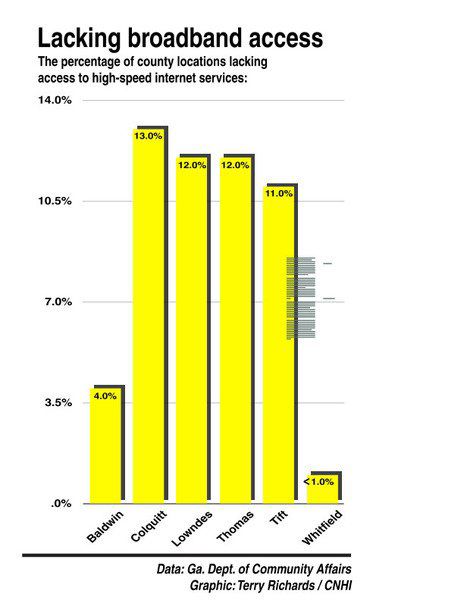

Even in the SunLight Project coverage areas, which include Valdosta, Thomasville, Moultrie, Tifton, Milledgeville and Dalton, access to high-speed internet varies greatly.

In Whitfield County, home to Dalton, less than 1 percent of the homes and businesses go without broadband whereas about 13 percent of them struggle with access in Colquitt County.

Some neighboring counties fare much worse. For example, only about 4 percent of homes and businesses in Baldwin County lack access while a stunning 86 percent go without a decent connection just one county over in Hancock County.

“When internet access is nonexistent or intermittent or unreliable, it cripples that person from meeting their objectives,” said Rep. John LaHood, a Republican from Valdosta who also represents Brooks County.

“Anywhere from individuals to families to businesses to hospitals without reliable high-speed internet, it puts them at a great disadvantage compared to areas that do have reliable internet,” he said.

Legislators passed a measure last year that created a framework for a grant program, but it remains unfunded. They also created a program that guides localities on how to become “broadband ready.”

‘Digital dirt roads’

Providers are often reluctant to invest resources in sparsely populated areas that do not yield the profits found in areas with greater head counts.

David DeSantiago said he gets that.

The 25-year-old lives in an area of southwest Brooks County that is surrounded by hunting plantations and about a half mile from a major highway. He moved there, he said, partly because the house was one of the few for sale in the area.

Like Radford, he said it is not the creeping internet speeds that frustrate him the most but rather the dangling promise from his provider that an upgrade is just around the corner.

“I’m not expecting fiber-optic cables or anything down there, but something more than dial-up (speed) would be nice,” DeSantiago said.

He said he is especially concerned about whether a new Boys and Girls Club complex being built in Brooks County, which is where he works as the athletic director, will have enough bandwidth to support about 50 kids participating in its after-school program.

DeSantiago said he would like to see a new provider enter the local market to introduce competition to an area dominated by just one player.

That’s where the electric co-ops can step in, said Sen. Steve Gooch, a Republican from Dahlonega who has championed rural broadband in the Senate.

“The return of the investment is so low in some areas that there’s not many companies out there that would want to invest in those areas because there’s very little to no return ever,” Gooch said.

“That’s why we think the EMCs are ideal because their main function and purpose is not to make a profit but to provide a service,” he said.

About a half dozen of the co-ops have started looking into whether they can afford to provide the service. At least two cooperatives in north Georgia are already selling the service.

Colquitt EMC, which serves Brooks County and several other South Georgia counties, might consider partnering with other providers if lawmakers approve the plan, said Danny Nichols, general manager. Nichols said his co-op is waiting to see whether lawmakers spell out in state law that electric cooperatives have the authority to sell the service.

If lawmakers go that route, telecommunication companies claim lawmakers should limit how much their new competitors can charge telephone and cable companies to put their wires and equipment on the vast network of cooperative-owned utility poles.

Gooch said he is working on a proposal to cap those rates and prevent a co-op from jacking up so-called “pole attachment” fees as a way to keep their competitor at a disadvantage.

At this point in the legislative session, the proposal is the only rural broadband measure gaining much traction under the Gold Dome this year, especially after Gov. Brian Kemp expressed some reservations this week about taxing digital goods and services to fund rural broadband expansion. That tax proposal would also lower the fee already tacked onto telephones and other more traditional services.

Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan also panned the tax proposal in a tweet.

“We’re going to build out rural broadband, but a new @netflix tax is not how we’re going to do it,” he said.

Duncan sounds keen on the electric co-ops. He said in a statement last week the Senate was working to “advance compromise legislation that would allow EMCs to enter the broadband industry.”

“We are aware that this is not a silver bullet, but rural Georgia can’t wait,” Duncan said. “It is time to deliver solutions that rid Georgia of our digital dirt roads.”

Jill Nolin covers the Georgia Statehouse for The Valdosta Daily Times, CNHI’s newspapers and websites.