Freedom of Information: Georgia laws demand transparency

Published 3:00 am Tuesday, January 2, 2018

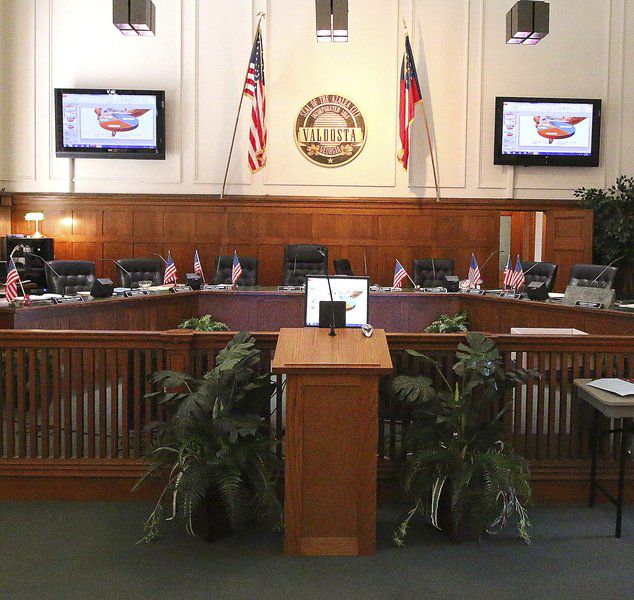

- Derrek Vaughn | The Valdosta Daily TimesPublic policy discussions must happen in open public meetings and not behind closed doors. An executive session is a portion of a public meeting lawfully closed to the public for very specific reasons.

VALDOSTA — Kejar Butler calls open government laws “the core of any democracy.”

The Thomasville City Board of Education member said Georgia Sunshine Laws help prevent closed-door government and she thinks that is a good thing, giving the public the right to access government information.

When lawmakers rewrote the state’s open meetings and public records laws five years ago, they sent a clear message that government transparency is the “strong public policy” of the state of Georgia.

The SunLight Project team of journalists takes a look at those state laws and provides information about how the public can access records, attend meetings and keep an eye on city and county government in Dalton, Milledgeville, Tifton, Moultrie, Thomasville and Valdosta.

Local Governments and State Law

Middle Georgia attorney Matt Roessing sees open government laws as necessary.

“I know that it is a bit burdensome for the government to comply with those requests and the posting requirements and all of that, but I do think it’s worth it; we need to know what our government is doing,” Roessing said. “In Georgia, we now have open government laws that allow more transparency than most other states. There was one case in recent years where a guy that was on death row was trying to find out why a prosecutor had made a certain decision 30 years ago, and the process of the open records request was very significant in his case.”

While no one the SunLight Project team interviewed opposed the state’s Open Meeting Act or Open Records Act, there does appear to be a difference between how government officials and the general public feels about how closely the laws are adhered to by city councils, county commissions, boards of education and law-enforcement agencies.

When the Dalton Board of Education was called into question about a lengthy — and overheard — executive session that included discussions on a wide array of topics including the retirement of the school superintendent and what that might mean for the future of the public school system, board members pushed back.

“Everything that I recall we talked about last night during the meeting had to do with a personnel matter or led to a conversation in relation to that personnel matter,” Chairman Rick Fromm said the day after the meeting. “What we talk about in the executive session is privileged and I review all of that beforehand with our attorney. In my opinion and the legal opinion of our attorney, everything fell under that purview.”

The school system’s attorney, J. Stanley Hawkins, was not present for that executive session, but said he questions the accuracy of a reporter’s account of what he overheard outside of the meeting, adding “based on what I read, I did not see anything that gave me pause.”

While not specifically referencing that chain of events, but open local government meetings in general, Dalton resident Charles Mathers said, “I’d really like to see the law require them to videotape all meetings and put them on their websites. Some of us can’t go to the meetings.”

Attorney General Enforcement

In the small town of Meigs, violations of the Georgia Open Meetings Act led to a $1,000 fine levied against the city council and specialized training by the Office of the Attorney General last year.

The Attorney General’s office is tasked with the enforcement of the state’s government transparency laws.

During the Meigs training, State Assistant Attorney General Jennifer Colangelo, said, “We try to just help the people understand what the law requires.”

Colangelo gave an anecdote on the importance of open government.

She described a scenario where children are playing and everything seems OK due to the jovial noise. She then told the council members to imagine the children suddenly quiet and going to check why.

“That’s how people feel about their government,” Colangelo said. “People have confidence in the government if they know it’s open.”

The Valdosta area is no stranger to open government violations, where in the past three years, local governments have come under fire for violation of the Sunshine Law.

The AG’s office has notified the Valdosta Board of Education and the Valdosta-Lowndes Hospital Authority of violations regarding meeting notices, minutes, agendas and executive sessions.

The Lowndes County Board of Education also came under scrutiny when a board member said he was party to secret discussions during an out-of-town retreat near Brunswick, where he said the BOE discussed hiring one of its own for a highly paid position within the school system. The board never followed through with the plans the board member said were discussed at that meeting

All three local governments have righted the ship and are now in compliance with state law.

The Lowndes County Board of Education member who came clean about the out-of-town retreat discussions is now school board chairman and has discontinued the practice of going out of the county for planning retreats vowing to keep the public’s business at home.

Public vs. Government Perspectives

When the Whitfield County Board of Commissioners in north Georgia planned to have a last-minute strategic work session during a meeting of the Association of County Commissioners of Georgia hundreds of miles away in Savannah, the newspaper posted an editorial on its website questioning the legality of the ad hoc meeting.

That editorial said, “Under state open meeting laws, the commission is required to provide 24-hour notice of all meetings. We received an email announcing the meeting from the Whitfield County clerk at 1:33 p.m. on Friday. The first meeting starts at 1 p.m. today (Saturday), meaning the county did not meet the 24-hour notice requirement. As of late Friday afternoon, the county still had not posted the meeting notice to its website. This is probably the first you’ve heard of the meetings. Depending on when you read this newspaper, the first meeting might be over.”

Board Chairman Lynn Laughter quickly contacted the newspaper, canceling the session “because of potential late notification.”

The public often expresses concern about what happens, not only in out-of-town gatherings, but on a regular basis, wondering if officials are discussing the public’s business outside of open, public meetings.

Tunnel Hills resident Tom Grant said, “The laws do what they can. I don’t think anyone’s having meetings and not telling anyone. But I do think they (elected officials) talk. One of them will call another. Then one of them will call a third one, so they usually know how they are going to vote before the meeting. How do you stop that?

Still, elected officials in city and county governments tend to say that nothing is afoul.

“I think it’s a pretty good balance that we have,” said Milledgeville City Councilman Walter Reynolds. “Of course, we can have closed-door meetings for personnel matters, which makes sense because you would want to be able to discuss matters regarding city employees in private. Pending litigation makes sense because you’d want to discuss your options with your attorneys in case there’s any sort of legal action being brought against the city. It also makes sense to discuss real estate purchases in private: if everybody knew about our intentions to purchase certain property, then property owners may decide to raise the cost of their property because they know there’s an interest in purchasing it.

“It’s beneficial to have those few things that we’re allowed to go into closed session regarding, but I don’t think there’s much else that a city council would need to go into a closed session to discuss.”

Milledgeville resident Eric Joy said he thinks the state’s open meeting laws are “a good thing.”

“I think when things affect us, we should be able to sit in and hear about those things,” Joy said. “If they don’t, I feel like they’d be shutting us out and that we would have less of a say. Would that be very unlike the dictatorships that we’re fighting overseas?”

Anna Young agrees.

“If you’re going to talk about what should take place in a town, I think the citizens should know about it,” Young said. “I know we elect officials, but our elected officials don’t always represent our best interests. You hope that the people you choose represent your interests but a lot of times they’re just out for themselves.”

But Alma Fleming, who frequently attends Moultrie City Council meetings, thinks city leaders do a good job of doing city business in the open.

“The ones that I know — Mrs. (Susie) Magwood-Thomas, Mrs. (Lisa Clarke) Hill and Mrs. (Wilma) Hadley — are doing the best that they can,” she said. “They always give the public the chance to speak. Anything that comes up they discus and they try to handle it.”

Fleming is Magwood-Thomas’ campaign manager for the November election.

James Tabor was at one time a fixture at Colquitt County Commission meetings. Since his absence for about five months due to health issues, there has been little, if any, members of the public in attendance with the exception of people with an issue in front of the commission such as a zoning request.

“I think they do a fair job,” Tabor said about the board’s openness to the public in doing the people’s business. “I think they do good. The only problem I see is not enough people come to the meetings.”

Tabor said commissioners spend little time in their meetings discussing issues but usually work quickly through the agenda.

“I think there’s a lot of stuff that’s already discussed,” he said. “When they come out, it’s just a formality when they come out in public.”

The commission holds work sessions prior to its regular meetings where it discusses issues on the upcoming agenda at length. The meetings are advertised and open to the public.

Tabor said he also has attended some of those sessions.

“They always treated me good when I got up there” to make a comment, he said.

Colquitt County Commission Chairman Terry Clark said the board rarely closes meetings and some discussions that could be taken behind closed doors are held in open session.

“The citizens deserve to know,” he said. “I’m all for open meetings so the citizens know what’s going on. There’s probably some times we should close them but we want to keep citizens (informed).”

In Thomas County, Commissioner Wiley Grady said he was elected by the public to serve the public.

“I had much rather be on the side of openness than to be accused of an impropriety,” Grady said. “You’ve got to be open. I don’t think the law is too strict. I think it’s perfectly adequate.”

Jay Flowers, Thomasville City Council member, thinks Georgia’s open meetings law is reasonable.

“I think the majority of the business should be conducted in public,” he said.

He added the city attorney does a good job of ensuring the council stays within the confines of the law.

Thomas County Commissioner Mark NeSmith is not the least bit conflicted about open government laws.

“It’s cut and dried. It’s the public’s business,” he said.

With the exception of permitted closed-door sessions for discussions about litigation and some real estate and personnel matters, NeSmith wants all commission business to be carried out in public.

“I’m not dealing with my own business, and the public has a right to know what’s going on in the meetings,” he said. “There’s no need to meet in secret.”

Still, Thomasville resident Earleen Williams does not think all government business is done in the sunshine.

“Some things are secret. Some are not,” Williams said. “Some things they don’t tell people. They sweep it under the rug.”

South Georgia civil rights activist Floyd Rose, who heads the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Valdosta, said he thinks most things are decided before public meetings are ever conducted.

“Every vote is unanimous and there are no discussions,” Rose said. “What does that tell you?”

Public Records

In addition to requiring that government meetings are open to the public, the Georgia General Assembly requires each local government to name a records custodian and to make public records easily accessible.

Government agencies can only deny an open records request when there is a specific exemption spelled out in the Georgia Open Records Act.

When a records request is denied, the government agency denying the request must provide the exact legal exemption, giving the specific code and section in the Georgia Open Records Act that allows the documents to be withheld from the public.

Paige Dukes, Lowndes County clerk and records custodian, said sometimes a lack of communication and understanding can create a rift between the public and local government regarding public records requests.

“Staff and officials try to work with citizens with regards to requests that are actually a question that needs to be answered, not a request for documents,” Dukes said.

“Sometimes there is confusion between the two. An open records request is a request for existing documents. It does not provide for documents to be created,” she said. “Regardless of the nature, every effort is made to provide citizens with their information. Local governments do not own information that is subject to the Open Records Act, they are only the repository for what already belongs to the public.”

Primer to Open Government

In this installment of the SunLight Project Special Reports, readers will find comprehensive coverage of open government laws in the State of Georgia.

Readers will learn how to file an open records request, where to file those requests, what records are exempt from the Open Records Act and what to do if a request is denied.

Learn when local government agencies can go into executive session and what they can and cannot talk about behind closed doors.

What must be included in meeting minutes and when is a public notice required? What happens when local governments violate the law?

Find complete resource guides and be introduced to the important work of the Georgia First Amendment Foundation and the Transparency Project of Georgia.

SunLight Project team members and other reporters who contributed to these reports include Charles Oliver, Chris Whitfield, Will Woolever, LaShaunda Jordan, Thomas Lynn, Terry Richards, Desiree Carver, Kimberly Cannon, Eve Guevara, Patti Dozier and Jordan Barela. The SunLight Project is overseen and edited by Jim Zachary and Dean Poling.