Ghost Guns: Valdosta lawsuit highlights problem of untraceable weapons

Published 6:30 am Saturday, April 29, 2023

- Untraceable

VALDOSTA — They can be deadly. They are out there on the streets and in homes, even in Valdosta. They can’t be tracked.

“They” are ghost guns — a slang term referring to guns built from kits ordered over the Internet, assembled by the buyer and often lacking serial numbers.

The number of these “privately manufactured firearms,” as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives calls them, is growing. The number of “PMFs” recovered by law enforcement agencies and submitted to the ATF for attempted tracing grew from 1,629 in 2017 to 19,273 in 2021 — a growth rate of more than 1,000%, ATF reports show.

A shooting in Valdosta

A Valdosta mother believes at least one of those “ghost guns” was responsible for her child being shot.

Shamiah Sharp is suing two online providers of gun assembly kits — Polymer80 of Nevada and Delta Team Tactical of Utah — in federal court for selling the parts needed to assemble a pistol used to shoot her son, referred to in court papers only as “Z.T.,” in the head.

Police were called out to a Melrose Drive home at 4:15 p.m., May 1, 2021, in a report about a shooting, according to a Valdosta Police Department statement.

A 14-year-old gunshot victim was found and taken to South Georgia Medical Center, according to the statement.

The lawsuit claims a minor referred to only as “J.C.” in court documents used her own money to buy gun assembly parts from Polymer80 and Delta Team Tactical and have them shipped to her home without a background check, violating a number of federal statutes, including rules requiring serial numbers on gun frames and prohibiting sales to a minor.

Using instructions provided by the firms and instructional videos, J.C. was able to build a working knockoff Glock handgun, according to the lawsuit.

While J.C. was visiting with Z.T. and other minors on May 1, the gun went off, putting a bullet through Z.T.’s head, the lawsuit claims.

The victim referred to as Z.T. in the filing suffered severe neurological injuries, pain, disfigurement and disability, resulting in permanent problems and the likelihood of future medical and rehabilitative expenses, Sharp claims in the lawsuit. She is seeking more than $75,000 in damages.

“This was a completely avoidable tragedy,” said Melvin Hewitt, an Atlanta attorney representing Sharp. “Anyone, including a 10-year-old, for example, can go on the Internet and make a gun … and now they have a toy that can kill.

“Is there exclusively prohibitive law everywhere that positively stops this? Perhaps not but even absent absolute irrefutable law aren’t things like this easily preventable?” he said.

Georgia has no law restricting untraceable firearms, according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

Sharp’s lawsuit could set a precedent for other civil cases, Hewitt said.

“Perhaps more importantly, it draws attention to things that may go unnoticed. I truly hope lawsuits like this bring attention to this. I know there are people on both sides of the issue but this case is not only about ghost guns … it’s about the sale of these things to children over the Internet.”

Attempts to reach representatives for Polymer80 and Delta Team Tactical were unsuccessful.

By the numbers

Hard and fast data on “ghost guns” is difficult to come by. Partly that’s because of the very nature of an untraceable weapon, said David Pucino, deputy chief counsel for Giffords Law Center.

“This is a problem we’ve seen across the country,” he said.

Most statistical information on guns used in crimes is gathered when law agencies ask the ATF to trace a weapon, he said. With no serial number, there is essentially no way to trace a “ghost gun” that has been found in the course of an investigation, rendering usable statistics difficult if not impossible to generate.

“We have a pretty incomplete picture,” he said.

Pucino said firms involved in online sales of gun kits are exploiting a loophole in federal law: since the weapons are a box of unassembled parts and not a finished firearm, they don’t count as guns and don’t have to carry serial numbers.

“They’re selling ‘guns’ without selling guns. That’s their business model — to sell these weapons to those who couldn’t get them otherwise,” he said.

The Biden administration has attempted to close that loophole, pushing a rule through the ATF that would require traceable serial numbers on gun frames and counting weapons kits as finished guns but that rule has been held up by lawsuits from the online gun industry, Pucino said.

Big city vs. small town

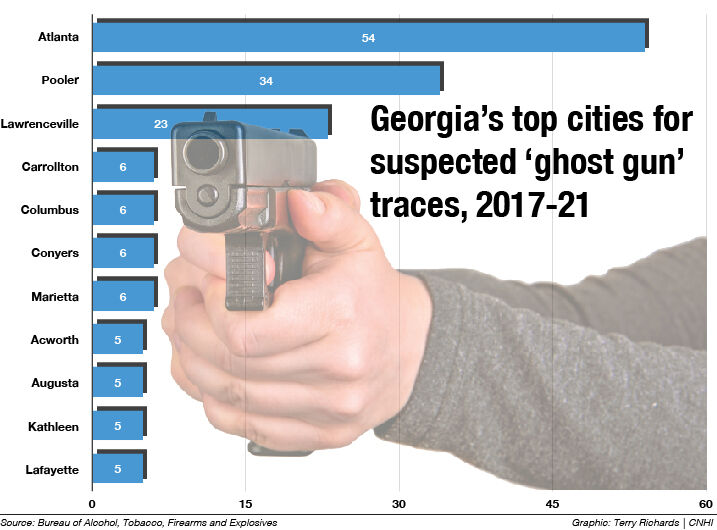

One of the few readily available sets of numbers for “ghost guns” is an ATF document showing the cities in Georgia with the most suspected “privately manufactured firearms” traces. Atlanta easily leads the pack with 54 but the numbers drop off sharply as smaller cities are counted.

Untraceable weapons are more of a problem in big cities, said Brad Shealy, district attorney for the Southern Judicial Circuit. He said his office hasn’t seen a criminal case with the online-ordered kit guns.

“(Having a ‘ghost gun’ in a case) wouldn’t affect prosecution,” Shealy said.

Lowndes County Sheriff Ashley Paulk said he thinks untraceable gun situations are still “a rarity” in this area.

“Most of the guns in crimes here are stolen right out of cars left unlocked,” he said. “So many people leave their cars unlocked. It’s unbelievable.”

Many of those who steal the guns don’t even bother to take the serial numbers off of them, Paulk said.

Valdosta Police Capt. Scottie Johns said the “ghost gun” case detailed in Sharp’s lawsuit is “maybe one of two I’ve ever heard of.”

Like Paulk, Johns said the majority of guns used in area crimes are stolen, often snatched from unlocked cars.

“Even the bad guys don’t want to be caught with a gun without a serial number,” he said.