Losing JFK: Looking back at Kennedy assassination 60 years later

Published 6:45 am Wednesday, November 22, 2023

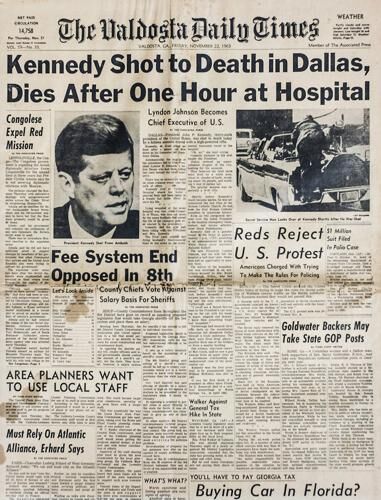

- The Valdosta Daily Times had to reset the front page of its afternoon edition on Nov. 22, 1963 for the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“Kennedy Shot to Death in Dallas, Dies After One Hour at Hospital”

That was the double-deck, banner headline that greeted readers of The Valdosta Daily Times on the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963.

The lead paragraph of the Associated Press story under this headline read:

“DALLAS — President John F. Kennedy, thirty-sixth president of the United States, was shot to death today by a hidden assassin armed with a high-powered rifle.”

Things were happening so quickly on that Friday afternoon of 60 years ago that AP incorrectly listed JFK as the 36th president, when he was actually the 35th president. But the deadline was tight for numerous newspapers across the U.S.

In those days, The Valdosta Daily Times was an afternoon newspaper. News of Kennedy’s assassination meant the front page had to be torn apart and re-designed to accommodate the bulletin news items that Kennedy had been shot in Dallas and then died.

With presses ready, there wasn’t time to change many of the inside news pages and still get the paper on the streets by afternoon.

The editorial page of that same day has stories with headlines reading “Republicans Make Leap Forward,” discussing GOP strategy against Kennedy for the 1964 presidential campaign, and “Kennedy Veers to the Right,” an article about the Kennedy administration’s legislative woes with Congress.

Additional stories about JFK’s assassination in The Valdosta Daily Times would follow in the next several days.

And stories about JFK, his life, presidency and assassination have been the subject and fodder of newspaper articles, magazine spreads, books and movies ever since.

The Kennedy retrospective came immediately after his death.

By January 1964, veteran Time magazine White House correspondent Hugh Sidey had a straight-forward JFK biography in book stores. The book was one of the building blocks of the post-Kennedy mythos of Camelot, America’s “loss of innocence,” the dashing and smashing of the New Frontier.

Sidey’s opening description of Kennedy, written a year earlier, set the mostly reverential tone for “John F. Kennedy President” — “Six feet; 172 pounds; 45 years old; a profusion of nondescript hair slightly out of control, strands of gray now on the fringes; gray-blue eyes; coarse and weathered skin with a fading trace now of Florida sunshine; straight mouth; a vestige of a second chin — a single human out of the world’s three billion, selected in this staggering lottery by the American electorate to control more power, either destructive or constructive, than any other man in history.”

Since the publication of Sidey’s JFK biography, the world’s population has surpassed 8 billion, and tales of Kennedy’s life, death and legacy have figuratively grown to similar proportions.

From the moment Jack Ruby shot and killed JFK’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, in front of millions of television viewers and the unsatisfying subsequent Warren Commission report, theories surrounding the assassination have multiplied from the feasible to the bizarre.

Since Sidey’s volume, hundreds of books and movies have explored darker dimensions of JFK’s life with relevant and strange allegations: the womanizing, a reported affair with Marilyn Monroe and dozens of other women, including a woman connected with a mob boss; that JFK was linked to Marilyn Monroe’s death; that he was addicted to pain killers and other prescription drugs for numerous debilitating injuries and maladies; that his father, Joe Kennedy, bought the election for his son and had JFK’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Profiles in Courage” ghostwritten.

There are numerous books, films and critiques on JFK’s administration, with some historians arguing that he was one of America’s greatest presidents, others arguing that he had the potential to be a great president and others noting that any greatness JFK attained is due to his assassination rather than his administration.

The list is nearly endless.

Though 60 years have passed since his death, the films and stories, the myths and allegations surrounding JFK continue to grow. Some new dimension to his life always seems to be ferreted out and the American public remains fascinated by it all.

He is demonized and praised. Some historians have claimed JFK was a borderline pain-pill junkie while president; meanwhile, essays, such as an Esquire magazine article early in the 2000s, touted Kennedy as the greatest man of the 20th century.

But why six decades after his death does JFK continue to fascinate?

True, Kennedy was the last president to die in office but he wasn’t the only one.

The first was William Henry Harrison, the ninth president, who died in 1841 of pneumonia about a month after taking office.

Zachary Taylor, the 12th president, died in 1850 of cholera.

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president, was assassinated in 1865 by John Wilkes Booth.

James Garfield, the 20th president, was assassinated in 1881.

William McKinley, the 25th president, was assassinated in 1901.

Warren G. Harding, the 29th president, died of a heart attack in 1923.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd president, died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1945.

And Kennedy was assassinated in 1963.

From 1841 to 1963, every generation experienced a president dying while in office.

Many American generations witnessed more than one presidential death. But we are a more than a half century since a president has died while in office — the longest period in American history that no sitting president has died.

The second longest stretch was 52 years, the period from George Washington being the first president in 1789 with no sitting-presidential deaths until President William Henry Harrison died a month after his inauguration in 1841.

Since Kennedy’s assassination, the majority of living Americans have never experienced the death of a sitting president.

Americans 60 and younger have no memory or personal knowledge of a president dying in office, except for what they have seen and heard thousands of times about Kennedy’s death.

And that repeated experience of viewing his life and death may be another important factor in why Kennedy still resonates with the American public.

Kennedy was arguably the first TV president.

Analysts, such as Theodore H. White in his classic book, “The Making of the President,” have claimed that Kennedy’s telegenic looks, his youth, his vigor, his charm, his eloquence, were perfect for the relatively new device of television in the 1960s.

White notes how viewers responded to Kennedy’s suave good looks as opposed to Richard M. Nixon’s sweaty, five o’clock shadow in their televised debate of 1960. White and others have asserted that Kennedy’s appearance during the televised debate helped him squeak by the more experienced Nixon in the election.

Through television, Kennedy entered people’s homes. For the first time, Americans could enjoy the comforts of their homes while watching a president walking and talking, playing with his children, addressing domestic and international matters and crises.

They could hear JFK speak, watch his lips move, see him refuse to wear the traditional top hat to his inauguration — as these events happened — while they sat in their living rooms.

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” spilled from JFK’s lips straight to the person sitting in an easy chair. People felt like they knew him because they saw him on TV in their homes.

His assassination and subsequent funeral assured part of the long fascination with Kennedy and cemented television’s place in American households.

Though the nation mourned the deaths of past presidents, they could mostly only read or hear about them. People wept at the news of FDR’s death in 1945 but most of the coverage of his funeral in that pre-television era was provided by newspapers, radio or newsreels at the local theater.

People had often heard FDR’s voice in their homes during his radio fireside chats but his face was relegated to newspaper and magazine photos and jumpy newsreel films. Most Americans didn’t even realize Roosevelt was usually confined to a wheelchair until years after his death because they rarely saw him.

Not so with Kennedy.

He may have suffered health problems but he was constantly visible on TV, his death was shown on TV and anyone with a television set in 1963 — and by then most households had one — could mourn alongside the widowed First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy.

They immediately witnessed young John Kennedy Jr. raise a hand to salute his father’s passing coffin. and we’ve been living with those images ever since.

With these images, Kennedy became more than a president. He became part of a communal mythology.

With so many photographs, so much television footage of Kennedy, he is always young and eternally handsome — though given the prevalence of the era’s black and white film, it is often easy to forget that had he not been assassinated, JFK could possibly have lived several more decades, though his health concerns would have determined how many more decades. But trapped in the amber of TV footage and photographs, JFK became iconic, a forever young emblem of Dionysian youth just as Marilyn Monroe and Jim Morrison are always young because of their ages at death and because of the technological age when they died.

JFK’s death sealed the culture of television and the coming of mass media, and it came at a pivotal point in American history.

For younger generations, it is difficult to relate that within a few months of Kennedy’s assassination, television rocketed a rock & roll group called The Beatles to superstardom on the Ed Sullivan Show.

In our era of viral videos and social media, it is difficult to grasp how TV captured the political turmoil of the 1960s.

Television brought JFK’s death and The Beatles into people’s homes, but it also brought images of Vietnam, civil-rights struggles in the South, anti-war protests from across the nation, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and JFK’s younger brother, Robert Kennedy, space flight and moon landings directly into people’s living rooms.

Television captured the defeat in President Lyndon Johnson’s voice and face in 1968 when he said he would not run for reelection and the surreal wave of President Richard M. Nixon’s “V for victory” departure as he left the White House in shame in 1974. Television chronicled America’s counter-culture, the Sexual Revolution, the demonstrations, psychedelic drugs.

And Kennedy’s death on Nov. 22, 1963, to many people and commentators, marked the beginning of these sea changes in American life and culture. JFK’s assassination became synonymous with the beginning of America’s political turmoil of the 1960s and into the ’70s, the cliched death of America’s innocence.

His death and the subsequent tragedies on the American stage have spawned a litany of “what if” scenarios: Would Vietnam have lasted as long or ended as poorly for the U.S. had Kennedy lived? Would public trust have eroded in America’s government institutions had Kennedy lived? Would America have reached a more equitable social plateau had Kennedy lived? Would the South have loosened its traditional Democratic stranglehold, as it did in response to Johnson’s domestic policies, had Kennedy lived? The “what-if” scenarios are almost as endless, and in many cases, as ludicrous as possible JFK assassination plots.

Would things have changed had Kennedy not been assassinated, had he survived to finish his first term and possibly win a second term? Undoubtedly.

Would his survival have meant a different conclusion to Vietnam? An easier transition to civil rights? A New Frontier? An American Camelot? Many historians say it is unlikely but we will never really know the answers to these questions, and that is part of the enduring appeal of JFK.

Because in 60 years of hindsight, America did change after the death of JFK, for the better and for the worse.

Yet, since those six decades, John F. Kennedy is still young, still seemingly vigorous and then suddenly an assassin’s bullet ended any further potential and impact he may have had as President of the United States.

Kennedy’s impact remains, oddly etched as a glamorous scar on the American psyche, a shining pockmark of lost potential. and it is possibly that shattered potential that fascinates us most of all.