Military surplus used for training

Published 11:20 pm Monday, November 10, 2014

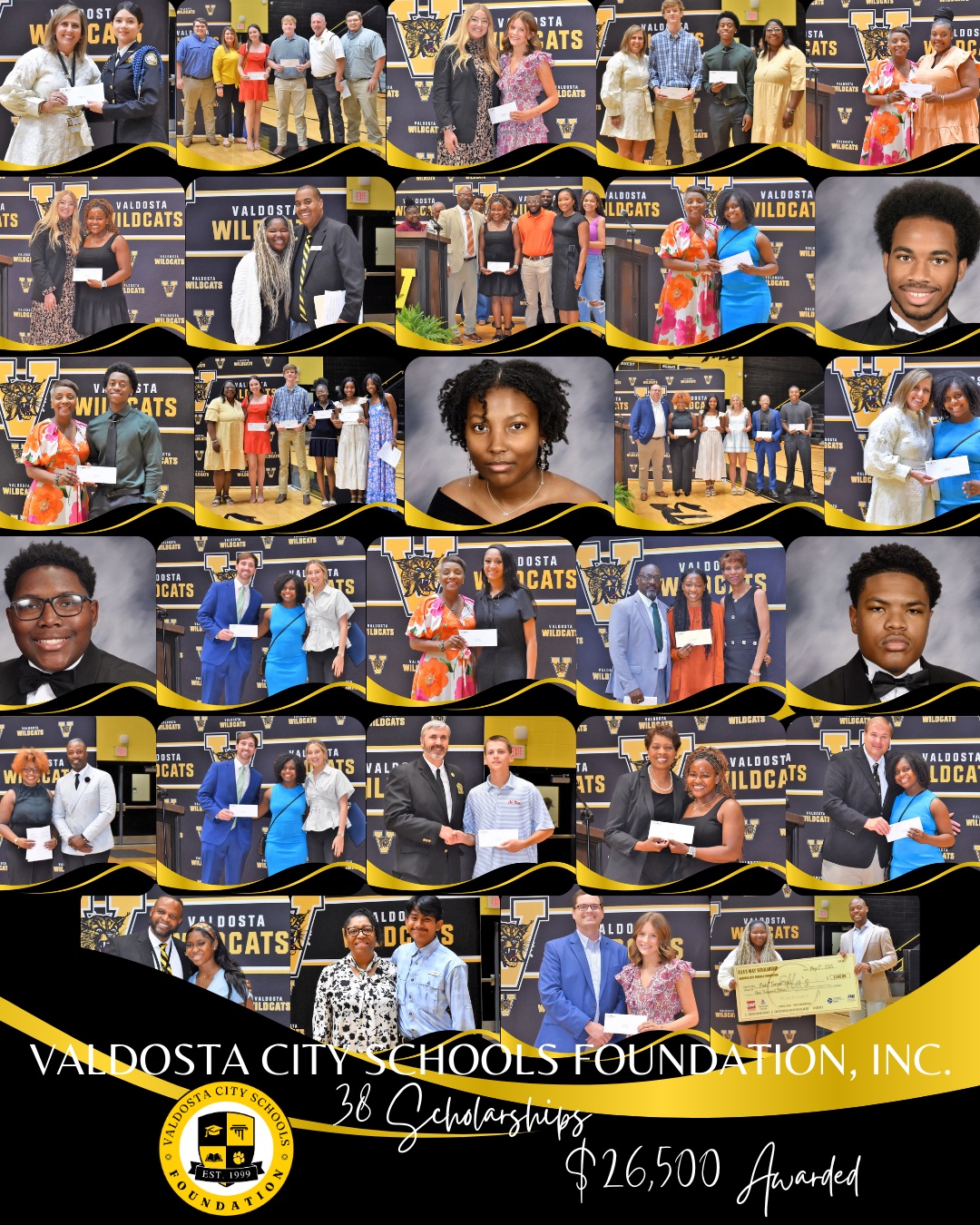

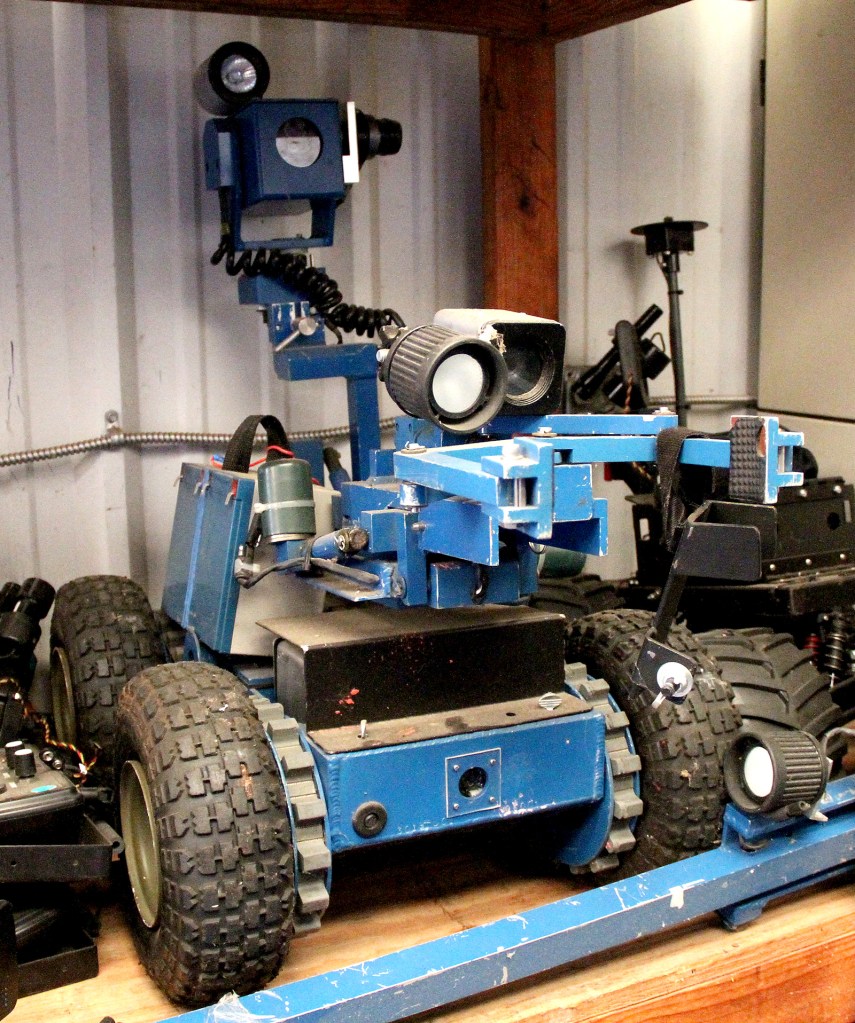

- LCSO obtained this robot through the 10-33 program. The sheriff’s office uses the machine for safety checks and to minimize officer exposure to dangerous situations.

VALDOSTA — In the wake of riots in Ferguson, Mo., concerns have been raised about the militarization of local law enforcement through a federal program that allows agencies to obtain surplus military equipment and weapons, but the use of the program in Lowndes County paints a more nuanced picture.

Critics say the 10-33 Program has allowed small police departments and sheriff’s offices throughout the country to obtain weapons and equipment that are not needed and unnecessarily militarized police tactics.

In a recent hearing, Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) said the program lacked oversight, and Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) said the program was “crazy out-of-control.”

Valdosta Police Chief Brian Childress said his department does not participate in the 10-33 Program, and he does not see that changing in the future. The Lowndes County Sheriff’s Office does, and Lt. Joe Dukes gave The Times a tour of their inventory and explained how the items are used.

“What we’ve been hearing in the public is weapons and armor,” said Dukes. “And for a time, I’ve really wanted people to see the other side of it.

According to Dukes, only a small fraction of the sheriff’s office’s 10-33 acquisitions have been weapons, and he should know. Dukes is responsible for acquiring and accounting for each item received from the program.

“I don’t even look for weapons. I haven’t since I took over the program about seven years ago,” said Dukes. “The weapons that we have now from the program, we’ve had for about twelve years, and we just continue to refurbish them.”

For Dukes, the real value of 10-33 is that it gives him no cost access to expensive items that can save lives. During a tour of the inventory, Dukes stood in a training room with large, flat floor mats, a digital projector and a gruesome mannequin used to train deputies how to treat traumatic injuries.

“There is a massive change in the way law

enforcement applies medical in the wake of active shooter scenarios, and a lot of the supplies we need are expensive,” said Dukes. “For instance, tourniquets. This one tourniquet costs 40 bucks. When you start talking about giving a tourniquet to every deputy, on tight budgets, that’s expensive.”

Dukes said the changes really began following the 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado.

“It was such a slow response, and that’s where law enforcement took a huge hit,” said Dukes. “It had always been that you wait on a SWAT team when you have something like that going on.”

Dukes believes more lives could have been saved during the tragedy if law enforcement had been able to provide a quicker response. The FBI is currently working to standardize the way agencies respond to active shooter scenarios to increase response times and effectiveness, said Dukes.

“Time is a key issue. When I come on scene, I may stop the killer, but there are bodies around. The medics aren’t going to be able to get in there because the scene is not safe,” said Dukes. “If I don’t have a shooter right then, maybe I can save a life.”

That’s where the training dummies and materials acquired through the 10-33 program come in. Dukes said every deputy is first aid and CPR certified but that training does not cover traumatic injuries.

“If you’ve got a gunshot wound to the femoral artery in your leg, you’ve maybe got five minutes to live. EMS isn’t going to get there in time in an active shooter scenario. The only way is for law enforcement to address that kind of problem,” said Dukes. “A tourniquet can do that. It’s great. But on hard budgets, it’s hard to get.”

Training suits are also hard to get. At around $1,000 each, purchasing new suits are cost prohibitive, but LCSO has obtained 15 suits from the government at no charge.

“They allow us to push the envelope on realistic training, and some of its greatest value is training a brand new detention officer,” said Dukes. “I can give him scenarios that he might run into at the jail. I can teach him how to de-escalate a situation. It, hopefully, reduces the anxiety of the jailer and teaches them how to use the proper amount of force in a situation or know when it isn’t a force situation. He’ll know because of the training.”

Dukes estimates he’s acquired $90,000 worth of training equipment without having to impact the sheriff’s office budget.

In addition to training and medical equipment, LCSO has received teaching tools like whiteboards and projectors, communications equipment, storage trailers, boats, clothing, office equipment, building materials and even robots.

“We started wanting a robot to be able to send into houses before we send a person for situations like a barricaded gunman,” said Dukes. “A perfect example of that was a guy who had barricaded himself, had a knife, screwed all the doors shut and was threatening to kill himself.”

Once an officer makes contact in a situation like that, according to Dukes, the chances of escalating the situation increases.

“If we can delay that, it’s better,” said Dukes. “We wound up sending the robot in to look for him.”

Deputies were then able to determine the individual’s exact location in the home and resolve the situation, said Dukes.

For Dukes, the robot allows deputies to “slow down and be patient” with people in crisis, something he hopes the department’s most expensive, and perhaps most controversial, acquisition will do as well.

Under a large white tent at the sheriff’s office is a mine-resistant ambush protected vehicle, commonly known as a MRAP Camion. The vehicles are designed to withstand improvised explosives and were widely used in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

LCSO obtained the sand-colored MRAP through the 10-33 program and has since painted it black, installed new seats with safety restraints and prepped it for use in a variety of situations from hostage situations to chemical attacks.

“Armored vehicles allow us to get closer and be more patient,” said Dukes. “Before, we literally had a bread truck that a .22 bullet could go through.”

Dukes said a vehicle like the MRAP will be useful in situations in which there is active gunfire and individuals need to be evacuate from an area.

“I can put family members in this, and I know with certainty that the family is safe,” said Dukes.

The vehicle has a contained air system that protects anyone inside from harmful chemicals or fumes, the kind that might exist in an event like a meth lab explosion. One thing the vehicle does not have is weapons.

“There is no offensive capabilities on this whatsoever,” said Dukes.

With the exception of two bean bag guns, which have never been used, the MRAP contains mostly rescue, safety and medical gear, but Dukes admits the vehicle can look intimidating.

“Perhaps the appearance may be intimidating for someone who doesn’t understand it, but when I see it, I see safety,” said Dukes. “And not just safety for law enforcement but for the community.”

Duke said he does not expect the vehicle to be used that often but is glad the option is available. Any use of the MRAP, according to Dukes, should be based on the situation.

“When you start talking about riot situations, I don’t see the need for pushing an armored vehicle through people exercising their freedom of speech,” said Dukes. “That’s what people saw in Ferguson. Now, I wasn’t there. I don’t know what intelligence they were working off of, but everything should be situation-based.”

Dukes said everything LCSO has obtained from the 10-33 program has been accounted for and inventoried.

“I’ve read some statements from politicians about the need for accountability. The 10-33 program has always been audited,” said Dukes.

The process involves several steps, including taking photos of equipment and serial numbers and uploading them to a federal website.

“I don’t understand how you get to the point where you don’t know where your equipment is. I have to account for everything,” said Dukes. “If I don’t, I get suspended from the program, and I imagine getting back on would be very difficult.”

Despite criticisms of the 10-33 program, Dukes sees it as a valuable resource for local law enforcement agencies that is less about the militarization of law enforcement and more about preparation. His goal is to build a Type II SWAT/Tactical team at the sheriff’s office that would be beneficial to the county and the region.

“We look at what’s the best equipment we can give that first responder to stop someone from killing,” said Dukes. “It’s not that you want it to happen, but if it does and you don’t have the equipment around and you did not equip your deputies, who is the public going to blame?”