‘This is my home’: DACA Dreamers living in fear

Published 4:00 am Sunday, June 30, 2019

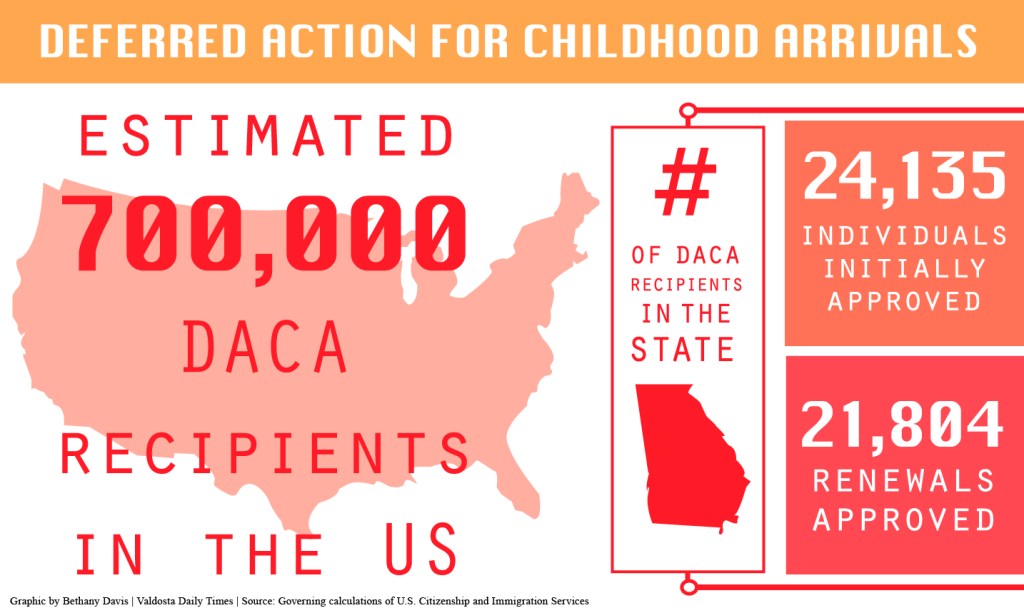

- Graphic by Bethany Davis | The Valdosta Daily Times

VALDOSTA — Julio Perez was only 6 months old when he and his mother boarded a plane from Mexico to Georgia, leaving behind their old lives — and country — forever.

She wanted to give him a better life.

And she did.

Now, however, Perez lives in fear that may all be lost.

He grew up in the United States. He went to school with American children, learned about U.S. history, went to church and celebrated traditional American holidays.

It wasn’t until he was about 13 or 14 years old, that he really noticed he was different from the other kids at school. While they were all getting ready to take driving lessons, his mom told him he wouldn’t be learning how to drive.

Because he was born in a different country, Perez and his family members were forbidden to get basic American paperwork such as a driver’s license or Social Security card. The full consequences of this fact didn’t sink in until later in his life.

“I started hearing stories that if immigration was in town and they caught you, they would send you back to your country,” Perez said. “I would worry about that happening.”

Everything came with a limitation and great deal of risk, he said.

The majority of job applications asked for a SSN, so Perez had to work for a business under the table.

When he was hired, Perez drove to work without a license. His mom told him to always drive carefully, follow the speed limit and stop at every red light.

Despite these warnings, Perez said he was still arrested on three different occasions for driving without a license.

Each time, he had to pay a hefty fine — up to $1,200 — and was released from jail.

“My parents still have to worry when they are driving to work without a license,” Perez said.

Lowndes County Sheriff Ashley Paulk said he and his deputies aren’t focused on ruining the lives of people trying to make a living.

Deputies will hold people accountable for driving without a license, but he isn’t going to call U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement on people for it.

“You run a sheriff’s department on three words: common sense and compassion,” Paulk said.

He said he will notify officials when they find someone with felonies, but for most cases, these are people just trying to provide for their families.

For Perez, ICE is an ever-present fear. It’s the boogeyman to people in the U.S. without documentation.

ICE could show up at anytime, take him away from his family and send him to a country he didn’t know with nothing but the clothes on his back.

They could take everything from him for the sole crime of being born somewhere else, he said.

Despite all of this weighing on Perez and his family and immigrant friends, they stayed in the States. They did jobs no one else would do and worked long hours in hot fields for barely enough money to get by.

Even after everything thrown at him, he said he never once thought about moving back to Mexico.

It isn’t home.

“America is one of the best countries in the world,” Perez said. “There are opportunities here for me and my family that we can’t get anywhere else.”

He wanted to become a citizen but said U.S. laws and regulations prevented him or made it nearly impossible.

The wait list in some cases could take between 15 to 30 years; he risked being sent to prison or back to Mexico during the wait, he said.

A ray of hope came in 2012, when President Barack Obama signed the executive order called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, an immigration option for undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. before the age of 16.

Although DACA does not provide a pathway to lawful permanent residence, it gives temporary protection from deportation, work authorization and the ability to apply for a Social Security number.

Perez was 22 when DACA was created, and he immediately headed to Chicago, where he heard he could get the needed paperwork. There, he joined thousands of people looking for protection and safety from ICE.

And … Perez was legally in the U.S. for the first time in his life.

“I was relieved,” he said. “It was a huge sigh of relief. I can’t even explain it.”

After graduating from high school in Moultrie, Perez wanted to enroll in college. Without a SSN, he could only apply to certain colleges and had no access to scholarships or Pell Grants.

Everything had to be paid out of pocket.

With his new status, however, it was easier to go to college, so he enrolled in Wiregrass Georgia Technical College.

Today, the 28-year-old DACA recipient works as a mentoring manager at an industrial company in Moultrie. He has an 8-year-old son, a Social Security number, a driver’s license and a feeling of security in his own home.

But all of the weight placed on him hasn’t been completely lifted.

His DACA status must be renewed every two years, which is always stressful, and his family still doesn’t have legal status. He said they drive to work every day putting their way of life at risk to feed and provide for their families.

The current administration makes him anxious about his future.

“I’m worried that it (his DACA status) could be removed at any minute,” Perez said. “I honestly don’t know what I would do if it is removed.”

If he loses his status, he would go back to square one, but this time there is more to lose.

His son is an American citizen born in the U.S.

Since leaving Mexico as a baby, Perez has returned only once about three years ago.

There is no life for him there.

Everything he has is in America.

He said he encourages people to learn more about the immigration system and the people who come to this country looking for a better life.

Perez has lived his entire life in the U.S. and considers himself a U.S. citizen.

“We’re not criminals,” he said.

Perez isn’t alone.

Jaime Rangel says Georgia is his home as well.

Really, the only home he has ever known.

He lives in Dalton, a community he loves; a community he wants to give back to. But his opportunities to give back were limited until 2012, when President Barack Obama created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

DACA recipients are often referred to as Dreamers.

Although DACA does not provide a pathway to lawful permanent citizenship, it does provide certain young people who came to the United States before the age of 16 temporary protection from deportation, as well as authorization to work in the United States and the ability to apply for a Social Security number.

“I believe I was 21 when DACA first started,” Rangel said. “When President Obama announced the DACA program it was an answer to my prayers. There was finally a program that allowed me to show the country that I was not a criminal, and that I’ve lived here my whole life. The program allowed me to work, go to college and give back to my community.”

Now 28, Rangel was brought to the United States from Mexico when he was 3 months old. He came to Dalton in the second grade.

Hundreds of thousands of young people across the nation — just like Perez and Rangel, live their lives with uncertainty and fear.

There are an estimated 700,000 DACA recipients in the United States and about 25,000 in Georgia. But the program’s future is uncertain.

President Donald Trump has vowed to end the program, but he has also called on Congress to make it permanent.

Rangel is a student at Dalton State College, pursuing a degree in finance and economics.

He must renew his DACA status every two years.

“It’s a very tiresome process having to renew my permit every two years and go through a rigorous background check and having to pay nearly $500, excluding attorney fees,” Rangel said.

“Not having some assurance by Congress to pass meaningful legislation does put a burden on me,” Rangel said. “I dream of one day buying a home in Dalton and raising a family here, but it’s hard having those dreams when down the road I could be deported from the only country I remember.”

It isn’t clear how many DACA recipients live in Dalton, but local officials say they play an important role in the community.

“I was talking to a group of about 20 of them about a year or so ago,” Dalton Mayor Dennis Mock said. “All of them had graduated from Dalton State College or were students there.”

Greater Dalton Chamber of Commerce President Rob Bradham said many local DACA recipients are in white-collar professions.

“With our unemployment rate as it is (4 percent in the latest numbers), if DACA goes away, that’s going to be a headache for our local employers who would have to fill those jobs,” he said.

It is difficult getting precise numbers on the impact DACA recipients have on their communities.

State Rep. Darlene Taylor, R-Thomasville, said to her knowledge, housing in Thomas County has not been affected by DACA.

Since the early 1980s, regulations for some housing benefits require citizenship for eligibility, said Taylor, who represents District 173.

DACA beneficiaries are not eligible for mortgages backed by the Federal Housing Administration, according to Housing and Urban Development.

Pat Holloway, chief of staff for Dalton Public Schools, said the school system does not ask students or their families if they are DACA recipients.

Bob Dechman, Thomas County School System assistant superintendent for federal programs, said schools do not maintain records on students’ DACA status and he is unaware of any DACA students enrolled in the district.

Ronn Ross, who has been Thomas County Department of Family and Children Services director for one year, said he has not had any case regarding the issue come to his attention.

Thomas University, a private university in Thomasville, has no DACA students, said Cindy Montgomery, director of marketing and communications.

The Technical College System of Georgia is not bound to DACA rules, said Brittany McInvale Bryant, director of marketing and public relations at Southern Regional Technical College in Thomasville.

“We don’t track the students that way, because we don’t fall under the same set of rules,” Bryant said.

Dalton State College officials said the school has no way to track how many DACA recipients are enrolled.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, Georgia is one of just six states that bar DACA recipients from receiving in-state tuition at public colleges and universities. In addition, the University System of Georgia bars DACA recipients from enrolling at the University of Georgia, Georgia Tech and Georgia College and State University.

“This really makes it hard for DACA recipients to become engineers and to become nurses and to achieve their dreams,” Rangel said. “I’ve been here practically my whole life, and I don’t qualify for in-state tuition, but there are people in Tennessee and Alabama and other states that can get in-state tuition if they live near the border of Georgia.”

State Sen. Chuck Payne, R-Dalton, said he believes the state should consider allowing DACA recipients who are residents to pay in-state tuition but only after the federal government has made it clear what it intends to do with the program.

“We need to wait to see what federal policy and law is going to be,” he said.

Rangel said he supports the American Dream and Promise Act, which passed the U.S. House of Representatives earlier this month. That bill would provide long-term residency and work permits to up to 2.5 million immigrants, including DACA recipients and provide many of them with a pathway to citizenship.

“The Senate should take up this legislation immediately and create a process for Dreamers like me to earn citizenship,” he said. “The American public strongly supports legislation that gives a pathway to citizenship to Dreamers and I will continue fighting for legislation that accomplishes that.”

Perez said he encourages people to learn more about the immigration system and the people who come to this country looking for a better life.

“We’re not criminals,” he said.

In addition to Charles Oliver and Tom Lynn, SunLight Project reporter Patti Dozier contributed to this story.