Rigsby realizes dream, completes Hawaii Ironman

Published 4:22 am Sunday, November 11, 2007

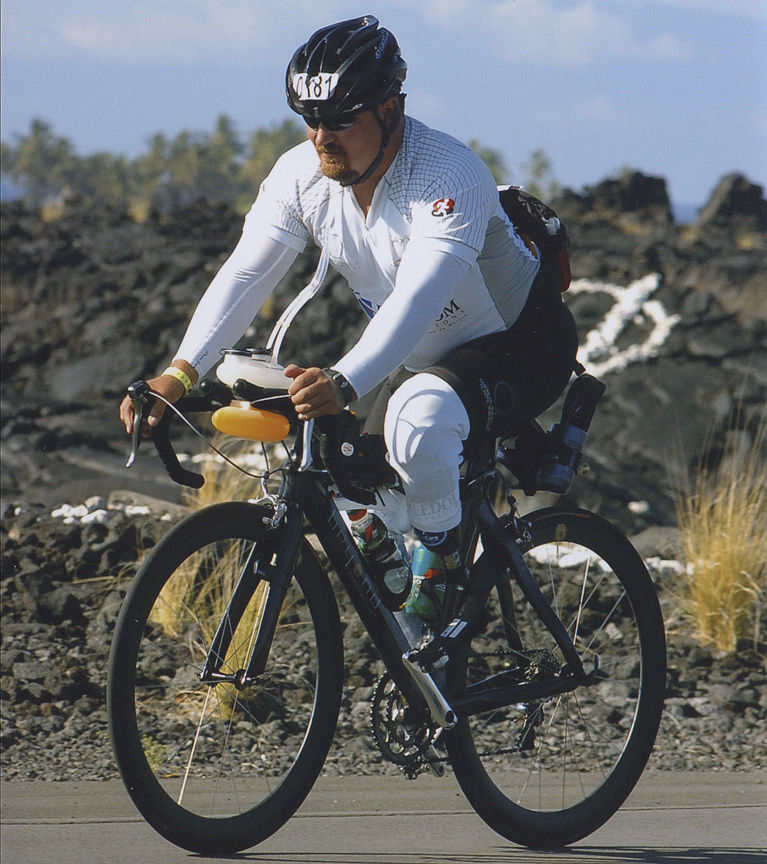

- Scott Rigsby rides his bike during the 140.6-mile Ford Ironman World Championships in Kona, Hawaii. Rigsby, a Valdosta State graduate who lost his legs in a car accident, competes using two prosthetic legs.

To say Scott Rigsby is an Ironman, is both the unbridled truth and an enormous understatement.

Yes, the former Valdosta State student officially earned the moniker Oct. 13 in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, finishing a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride and a 26.2-mile marathon in 16 hours, 42 minutes and 46 seconds.

However, the metal Rigsby should have attached to his name should be something stronger, and more indestructible than iron, perhaps titanium, or more appropriately, some foreign substance that can withstand obscene amounts of torture.

That’s exactly what Rigsby did, as he became the first-ever below-the-knee double amputee to finish an Ironman event.

Rigsby overcame a mental breakdown and an allergic reaction leading up to the race. Then, once the race started, he suffered a kick to the eye during the swim portion, tremendous head winds during the cycling portion, and a nearly race-ending fall on the running portion, all on his way to achieving his goal. Oh yeah, Rigsby overcame those obstacles without legs.

“It’s kind of feeling like you’re working on a project like a carpenter, building something and getting to the end of building a house,” Rigsby said. “You’re finished, have sweat dripping off you, you have a hammer in hand and a bag of nails. You step back and look at the house, and it’s wonderful, because it’s finally built. I feel like I built a house God allowed me to build.”

The personal trials and tribulations leading up to the world-famous race were nothing compared to how he got to this position. Rigsby was injured in a car accident in 1986, causing him to lose his right leg, and in 1998, he had the left one amputated.

Since 2005, his purpose in life has been to show others with disabilities, especially those in the armed forces that suffered injuries in war, that life goes on after a person is disabled. He decided to become the first double-amputee to complete an Ironman.

He made his first attempt June 24 in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, but came up short, due to a cycling crash that fractured vertebrae in his back.

The injury left Rigsby sidelined for a short while, allowing him to train for just 100 days leading up to the Ironman Championship, a race that generally requires about five months to prepare for.

Along with the injury, Rigsby’s bills were piling up, as well as the pressure from his parents to concentrate more on his financial situation. He needed all his time to train, and work wouldn’t allow him to be physically prepared for the challenge of a lifetime, so he relied on sponsors.

“I had no sponsorship dollars coming in,” Rigsby said. “You don’t get any sponsorship because you almost win the game.”

About six weeks before Rigsby made history, one of those crucial plot points where film directors insert depressing music right before a sunrise scene occurred.

“I remember a critical moment, where I was supposed to do five hours on a bike,” Rigsby said. “I got to the point where I had all my stuff together, and was about to walk out the door, but I couldn’t walk out the door. I almost had this panic attack, where I put my hand on the door, and couldn’t turn the handle.”

After sitting with a stare focused on the door, Rigsby drove around in his car, when his training partner Mike Linhart called to check up. The former Army Ranger, told Rigsby to focus on what is right in front of him, and forget about the tasks mounting ahead of him.

“It was some of the best advice I’ve had in my life,” Rigsby said.

That advice carried Rigsby to Hawaii, where he stayed at a bed and breakfast in Puako.

At the bed and breakfast, which granted him a complimentary stay, he would again struggle with continuing.

“During training, I had a miserable experience,” Rigsby said. “It just seemed like I was on fire. I couldn’t do anything to cool down my body. In the meantime, I’m walking around the house, sweating like crazy, and I can’t figure out why I’m breaking out in a rash all over my neck and chest.”

It turned out that the owners used a specific detergent that caused him to break out in an allergic reaction.

It took two days for Rigsby to start training again, with the help of Benadryl, just 23 days before the World Championship.

When the day came to put all his training, dreaming and praying on the line, Rigsby woke up at 3:30 a.m., and hit the water hours later with the 1,799 other participants.

Heading into the water, Rigsby had thoughts of finishing, and so did his fellow competitors.

“One of the athletes said, ‘You’ve got to finish this race. If you finish this race, you can change the world. Our military men and women need you,’” Rigsby said. “I got the message loud and clear.”

Rigsby made it through 2.4 miles in the Pacific Ocean in 1:28:48, despite getting kicked in the eye 200 meters in.

The switch to the bike went well, and Rigsby was pedaling along when the Hawaiian crosswinds caught him at about 30 miles per hour.

The winds slowed him down to about an 8-mile per hour pace, and finishing the upcoming marathon through the added fatigue looked grim.

Rigsby looked to God, as he has so many times throughout his life, and this time there was no answer.

“Since He was not (responding) to me, I thought what would He tell me if He was,” Rigsby said. “He would tell me to control the things that I can control, and not worry about the rest.”

Rigsby controlled the cadence of his pedaling, lightening up on the bike’s tension, and controlling his heart rate. After he achieved those two strategies, he was back riding at 25 miles per hour, finishing the 112-mile course in 8:19:30.

He then ditched the bike, and attached head lamps to his legs, given to him by a company called Fuel Belt. The lights enabled him to see where he was running, since he could not feel the road with his prosthetic legs.

He was slower on the running portion than usual, due to having to dump sweat out of where his prosthetics met the remainder of his legs every four miles.

At mile 19, Rigsby lost his balance and fell to the ground, landing in the pushup position. If his legs would have touched the ground, the seal on his prosthetics would have been compromised, and the race would have been over without him crossing the finish line.

Instead of his legs hitting the ground, the lights stuck out just far enough that it acted as a buffer, saving the race.

Rigsby then plowed through the greatest pain of his life, finishing the last nine miles 25 percent faster than the previous 17.

“I started thinking about why I was here,” Rigsby said. “God gave me a door, and I’m going to run through it.”

Rigsby also thought about his older brother, who suffers from mental retardation and cannot run with legs or prosthetics.

“Not finishing was not an option,” Rigsby said. “Even if I had to crawl.”

Seventeen minutes, 14 seconds before the deadline for finishing the Ironman, Rigsby heard a roar louder than any Georgia Bulldogs game he has ever been to at Sanford Stadium. That roar was for him.

He crossed the finish line, and posed for the crowd, where the Voice of the Ironman, Mike Riley, said the words every triathlete dreams of hearing: “Scott Rigsby, you are an Ironman.”

The next day, when Riley asked him how it felt to make history, Rigsby answered, “like Neil Armstrong after a bar fight.”

Indeed, the painful part was over. Both the physical pain of the most trying race in the world, and the mental pain of overcoming the loss of two limbs.

Now all of the hard work leads up to building up the Scott Rigsby Foundation, and making his pain ease that of others. Rigsby has gained the attention of media throughout the world, with his story to be broadcast on NBC’s telecast of the Ironman World Championship on Dec. 1.

“My goal is to build a legacy,” Rigsby said. “My success isn’t going to hinge on whether or not I finish one more Ironman or 50 more, but if another double-amputee shows up at a race and is doing this because ‘If Scott Rigsby can do it, I can do it.’”