Finding ‘Doc’: Meet Valdosta’s most infamous resident

Published 11:30 am Saturday, February 9, 2019

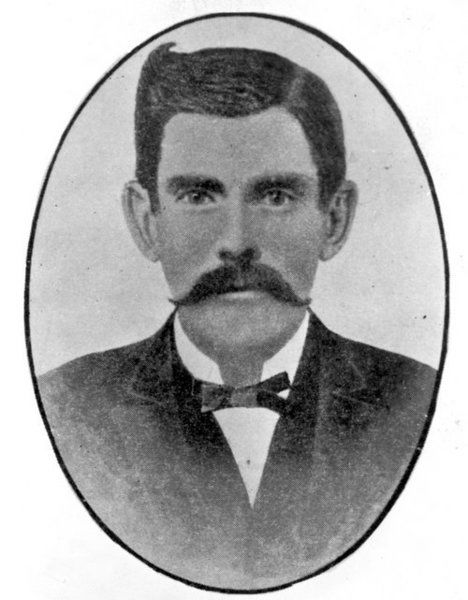

- John Henry ‘Doc’ Holliday

VALDOSTA – John Henry Holliday was a complex man who has left something of a complex legend.

He was a dentist which led to his nickname of Doc Holliday.

Trending

He is also known as a gun slinger. A gambler. A drinker. A tragic figure suffering tuberculosis who courted death.

He has been portrayed as campy court jester; loyal friend, the moral conscience and ghastly reminder of mortality to Wyatt Earp; reluctant gunman; a sagebrush sage; a roughhewn sidekick; a well-educated fop; a daredevil, etc.

But one thing few of the biographies mention, and none of the movies, is that Doc Holliday was also a Valdosta resident in his youth. That is a fact.

Where the

legend begins

Trending

Distinguishing parts of his Valdosta stay from the legends that have become his life is at times as overwhelming as the task has been to separate history from myth in any number of dimensions arising from Holliday and Wyatt Earp’s involvement in the O.K. Corral as well as any number of their other adventures which may be fact or fiction.

Legend has it that young John Henry Holliday killed a soldier in Valdosta and fled the region to avoid prosecution.

A few years after the Civil War, according to Lee Paul’s “John Henry Holliday: The Living Dead Man,” Holliday and family members often swam in a water hole near the Withlacoochee River on family property.

On one occasion, according to the tale, John Henry Holliday and relative Thomas McKey reportedly discovered several black Union soldiers, stationed as the occupying force in Valdosta, swimming at the site. John Holliday reportedly told the Union soldiers to leave, but they refused.

“John pulled his pistol, a Colt 1851 Navy revolver, and shot over their heads,” Paul writes. “Scholars differ on what happened next. Some claim he killed two of the soldiers and wounded one more. Others say he only killed one, that the others scattered. In any event, the incident was blown out of proportion to become a small massacre. It forced John to leave town” and be sent to dental school far away to protect him and the family from the matter.

Legends then have him embarking on any number of violent incidents. In 1875, Doc was reportedly involved in a Dallas shooting incident where no one was killed but he was found not guilty of a charge of assault to murder. In 1877, Doc is shot after beating a man with a cane in Breckinridge, Texas.

That same year, Doc reportedly fatally stabs a man at a Fort Griffin, Texas, poker table, after politely warning him and after the man drew a gun on him, but Doc escapes with help from companion Kate Elder. In 1878, Doc runs a man out of Dodge City, Kansas, by drawing his gun and, two years later, shoots this same man for drawing on him in Las Vegas.

In 1878, Doc draws his gun to help friend Wyatt Earp who is surrounded; Doc may have shot a man in this encounter. In 1880, Doc and another man were reportedly disarmed after drawing on one another in the Oriental saloon in Tombstone, Ariz., where Doc later returned to shoot the bartenders who disarmed him.

In 1881, Doc reportedly joins a posse headed by Wyatt Earp and brothers to dismantle a group of stage robbers, which leads to the deaths of Old Man Clanton. On Oct. 26, 1881, the shoot-out at the O.K. Corral pits the Earps and Holliday against the Clanton-McLaury clan in Tombstone, and Doc kills two McLaurys, one by shotgun and the other with a nickel-plated pistol. Doc is also involved in a stand-off with Johnny Ringo, and a posse that kills several men, which may have included Ringo, as well as the shooting of a man in self-defense in Colorado in 1884.

These are just a few of the violent incidents attributed to the career of Doc Holliday, which does not take into account the numerous shootings included in fictional and semi-historical movies.

But the late Susan Thomas McKey, a Valdosta resident and Holliday second cousin who has studied Doc for years, said in a past article she has found no evidence that Holliday killed anyone other than one man in the famed incident at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone.

While legend, movies and even some historians have embroidered a bloody legacy for Doc Holliday, including the reason for his departure from Valdosta, much of his early life and time in Valdosta has been avoided and untouched by legend.

Serious research by people such as McKey discovered evidence to verify many of the events in his childhood and young adult life.

Doc: The Early Years

John Henry Holliday was born to Major H.B. Holliday and Alice Jane McKey Holliday in Griffin in 1851.

Records show John Henry was baptized as an infant on March 21, 1852, in the First Presbyterian Church, according to “In Search of the Hollidays: The Story of Doc Holliday and His Holliday and McKey Families,” a book by Thomas and Valdosta-Lowndes County historian Albert Pendleton.

In 1864, when John Henry was about 11 or 12, and the Civil War was seeing the advance of Union troops across the South, Major Holliday moved his family to South Georgia, specifically the young Valdosta and Lowndes County, to protect them from Union advances. Valdosta of 1864 was a small town, only four years old, with wood buildings and no paved streets.

The Hollidays were a substantial middle-class family of Scottish-Irish descent, who made Valdosta a home for themselves and their extended family. The Hollidays immersed themselves in the development of young Valdosta, and Major Holliday twice served as Valdosta’s mayor.

Despite Valdosta’s small size, John Henry received a first-rate education from the private Valdosta Institute, where he likely studied the curriculum of math and science, Greek, Latin and French. He likely explored the woods surrounding the area, as he grew up in the post-Civil War era of Valdosta and the South.

In 1866, his mother died reportedly of tuberculosis, often referred to in the 1800s as “consumption,” the same disease that would later claim Doc’s life.

Alice Jane McKey Holliday was reportedly the stabilizing factor in young John Henry’s life, and her death left a melancholy mark upon him. His relationship with his father became more strained when Major Holliday married Rachel Martin, 23, later that same year.

In about 1870, the incident with the occupying Union soldiers occurred in the watering hole. Thomas says her family admitted the incident occurred, but that no one was killed. “Doc shot over their heads,” according to the family accounts, and no evidence or records have been found that anyone died in the incident, Thomas said. John Henry Holliday may have also been involved during this period in a thwarted plot to “blow up” the Lowndes County Courthouse, which had become the headquarters of “carpet baggers” in the post-Civil War days.

Thomas noted there is no evidence to confirm young Holliday’s involvement.

Still, during this same period, John Henry Holliday left Valdosta.

After Valdosta

For many years, scholars, including Thomas, thought Holliday enrolled in a Baltimore dental school, but Thomas’ research uncovered his attendance and subsequent 1872 graduation from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery in Philadelphia.

Upon graduation, he returned to Atlanta, where he practiced as a dentist for a short period of time in 1872, on the corner of Alabama and Whitehall streets, according to the Thomas-Pendleton book. A newspaper notice in The Atlanta Constitution has him practicing with a Dr. Arthur C. Ford.

He then practiced dentistry briefly in Griffin, though there is no written verification that Holliday practiced in Griffin. In this same time, Holliday was diagnosed with tuberculosis and given the medical advice to leave Georgia’s wet climate for a drier climate to prolong his life.

“It is believed that he left Georgia for the West in the latter part of 1872, or the early part of 1873,” according to Thomas and Pendleton.

He traveled to Dallas, where he established a dental practice and also became involved in the aforementioned shooting incident, according to “In Search of the Hollidays,” which lists many of his reported travels as well as reported scrapes, though Thomas reiterates the evidence only corroborates that he killed a man at the O.K. Corral.

Origins of the Gang

By the late 1870s, Holliday met both Kate Elder, also known as “Big Nose” Kate and Kate Fisher, who was reportedly Doc’s wife though Thomas never found evidence to support this claim, and Wyatt Earp, who became his friend and connection to immortal fame or notoriety.

Holliday and the Earps were the victors of the O.K. Corral shoot-out, a stand-off of a few bloody seconds that has since inspired all of the other legends, movies, etc. By 1887, though, John Henry “Doc” Holliday succumbed to tuberculosis after being bed-ridden for a considerable length of time. He died in 1887 in Colorado at the age of 36.

In many ways, the legend of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and the O.K. Corral nearly died with Doc. The O.K. Corral made headlines across the nation, but it didn’t capture the immediate staying power of the legends of famed Western Bills, such as Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickock or Billy the Kid, or the truly reckless nature of Jesse James and the Daltons.

True, Wyatt Earp made a living out of his exploits for the next several decades, surviving long enough to witness the coming of movies and their early love of the mythological Old West.

Myth vs. Legend

Wyatt Earp told the tale in a way that mythologized and aggrandized his participation in the taming of the West. Shortly after Earp’s death, Stewart Lake created the legend of Wyatt Earp as a man of clean-living justice, which history shows that Earp was not.

Though Lake and Earp had met, Lake wrote the book as if Earp had dictated much of it to him verbatim, but Lake created most of these lines from his imagination. Fifty years after the O.K. Corral and nearly 50 years after Holliday’s death, the legend was born anew.

Throughout the 1930s, authors wrote books. Hollywood made movies. Survivors who outlasted even Wyatt Earp shared their accounts.

“The world knows Wyatt Earp,” Susan McKey Thomas said in a past article, “because he lived the longest, far longer than Doc, and was able to shape the story the way he wished.”

So, Doc Holliday became a supporting character to Wyatt Earp. Holliday became the rogue while Earp was often portrayed as the hard-charging lawman. It is a contradicting depiction that Thomas finds especially troublesome.

“The Earps were what I would describe as earthy people,” Thomas said, “while Doc had a first-rate education and cultivation.” If there was a more civilized, urbane and more sophisticated member of the Earp-Holliday team, it would be Doc, she notes.

Meanwhile, Doc was also part of a family that for many decades regarded him as a black sheep and rarely spoke of him. So, when subsequent descendants came, such as Thomas, who found the family connection to Doc distant enough to be fascinating rather than embarrassing, there was little family lore or history from which to draw.

Thus, compounding the legend and further blurring the line between Doc Holiday the myth and the man.

“Unlike his peers, he did not live to write his biography. He died at the age of 36,” Thomas notes in a short Doc bio for the Lowndes County Historical Society. “Perhaps researchers and writers need to take a second look at this man’s life. Maybe somewhere in between John and Doc lies the real John Henry Holliday.”