More than a coach: Hyder’s legacy lives on with former players

Published 7:37 pm Saturday, August 6, 2016

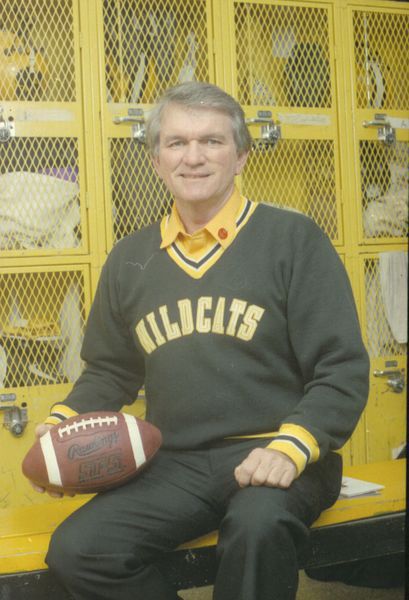

- File photoLegendary Valdosta coach Nick Hyder poses in the Wildcats' locker room.

A dynasty requires more than one individual.

In 1971, Wright Bazemore relinquished his throne as coach of the Valdosta Wildcats, ending perhaps the best era in high school football history. Unbeknown to America, the ‘Cats were just getting started.

Trending

It’s difficult to follow success. Perhaps one can surpass his or her predecessor, but not without being shrouded in debate. History is a timeless tale of such: Hank Aaron vs. Babe Ruth, Steve Young vs. Joe Montana, Michael Jordan vs. LeBron James, Brett Favre vs. Aaron Rodgers. Comparisons are human nature, yet often subjective. Comparing great sports figures isn’t always as black and white as stats suggest.

In professional sports, teams can maintain stars at a price, essentially paying for success. In college athletics, exceptional coaches and programs will always pull recruits. In high school, one’s coaching and leadership is truly tested. The challenge is unique. Consistency is nonexistent. In South Georgia, expectations can be a coach’s biggest foe.

Coming into the post-Bazemore era, Nick Hyder stepped into a situation which demanded excellence. His story is one of a man who equaled, if not exceeded, previously unparalleled success — both on and off the gridiron.

A coaching career consisting of 302 wins to 48 losses and five ties only scratches the surface of Hyder’s football success. He won three national champions with the Wildcats (1984, 1986 and 1992). He finished six seasons with a goose egg in the loss column. Valdosta won seven state titles, while Hyder won seven Coach of the Year honors, including national acknowledgement in 1984. The Wildcats went 125-10 in the 80s, with an 86-4 showing in the regular season. He finished 249-36-2 at Valdosta.

To many who knew him, Hyder was a byproduct of hard work. With his father a principal and his mother an English teacher, he was raised with an academic background. As an only child, his parents always pushed him. When Hyder couldn’t get playing time as a ninth grader, his mom told him to get better and stronger. So Hyder would carry concrete blocks and rocks around his backyard as an extra effort. Never giving up became a theme of Hyder’s life.

Hyder’s coaching career was catapulted at West Rome, where he replaced Paul Kennedy, his uncle, as head coach. Hyder went 53-12-3 in Rome before moving to the Azalea City. He also helped the baseball team to a 124-67 record and two state titles.

Trending

But West Rome had its limits. Rival East Rome shared the district, so any requests to the central board of education had to accommodate both parties.

“It was a situation where Nick couldn’t get anything he wanted,” said Charles Tarpley, who coached under Hyder in Rome and Valdosta. “Not money-wise, but if he would ask for weight equipment, the board would say ‘well we can’t afford to give both of y’all improvements.’”

Conditions never improved. Tarpley recalls Hyder going to Kansas City and purchasing buses himself, then having them painted WRHS colors. Even under less than ideal circumstances, Hyder’s teams won. Schools around the state became well aware of his resume.

Hyder received job offers from Clarke Central, Newnan, Griffin and others. But when Valdosta called, it was an easy choice, according to Tarpley.

“(Hyder) came back and said ‘I just can’t turn it down,’” Tarpley said. He added that besides the winning tradition, Hyder found a one-school system appealing. Due to family circumstances and his relationship with Hyder, Tarpley declined a head coach recommendation at West Rome in favor of joining Hyder with the ‘Cats in 1974.

The process wasn’t so simple for Valdosta — the transition from Bazemore to Hyder had its blemishes. Bazemore’s retirement opened the door for assistant Charlie Greene to take the reins. Greene won 17 of 20 games in two seasons, but resigned. The details of his resignation remain foggy, but sources close to the program cited disciplinary issues as the root of his demise. Hyder, a disciplinarian, was seemingly a perfect fit.

David Waller, chairman of the board of education and key member of the search committee which hired Hyder, said it was love at first sight.

“Once we met Coach Hyder, we fell in love with him,” Waller said. “He’s one of the greatest men I’ve ever known … He was a different breed. He never wavered in what he believed in. He came along and lifted our program higher than ever before. I wish he was still here today because no doubt in my mind he’d still be winning.”

The winning wasn’t immediate, however. Hyder’s Valdosta career began with a thud. After dismissing more than 10 players for rule violations, Hyder’s Wildcats went 3-7 in his first season, which was the school’s second-worst record ever at the time. Former Valdosta defensive coordinator Jack Rudolph remembers requests for Hyder’s firing. Tarpley, the only person present for all of Hyder’s victories, said the pressure was heavy and unlike that of Rome, describing the situation as “miserable.” He said Hyder even received threats.

“It was much more pressure when we got here because in West Rome, we didn’t feel any pressure whatsoever,” Tarpley said. “Nick always said, when you got here, you didn’t realize you had packed stands and every human being there knew what was going on. He said he’d have little old ladies coming up to him after games telling him what (play) he should’ve run. Valdosta people knew the offense, knew the terminology, knew the situation … When you fire someone who was 17-3, then hire someone who goes 3-7…”

But Hyder wouldn’t surrender. He quickly flipped the script, endearing himself to fans along the way. The team was a serious contender in Year 2. He abandoned his preference of the wishbone offense in favor of Bazemore’s spread attack. He had bonding get-togethers for his coaches and their families. He kept the same staff throughout his tenure. The winning culture was re-established and the atmosphere was one where players would run through a wall for their coaches.

Religion was a focal point of that atmosphere. He invested personal time to share his faith with others. Waller spent many late nights praying with Hyder. Before and after practices, Hyder would always talk with his players about non-football issues. He used his status to spread a message.

“Nick never found a speech 400 miles away that he wouldn’t do,” Rudolph said.

Hyder traveled across the country, even on weekends during the season, to speak on larger platforms. He wanted to instill the same values that brought him success upon others, according to former Valdosta defensive end Don Baker. With Hyder’s own players, Baker said religion was a constant conversation, but never forced. Hyder spoke “to” his players rather than “at” them.

“There are several guys who got into coaching and ministry because of him,” Tarpley said. “His life was religion and Valdosta football.”

Hyder had more in common with Bazemore than school and victories. Similar to Bazemore, Hyder didn’t curse, drink or smoke. He wanted his players to see the bigger picture, and the best way to do that was to set an example.

Rudolph coached Valdosta’s defense for 30 years under Bazemore and Hyder. He said both coaches shared the same values. Both wanted to develop young men into adults more so than high school athletes into professionals. Both knew how to take control and get results in an elegant manner.

As with all families, the coaching staff had disagreements. Tarpley recalls Hyder “getting onto” coaches for cursing. Rudolph said it was easier to protest Hyder than Bazemore, and arguments were a staple of coaches’ meetings.

“If things didn’t go Nick’s way, or he was losing an argument, he’d raise his voice,” Rudolph said, laughing. “Now he wasn’t a profane talker, but he was an arguer.

“I got fired three times in one week.”

The aforementioned Don Baker, who played for Valdosta in the early ’90s and was a defensive captain on the ’94 team, was the son of longtime assistant coach Jerry Don Baker. Don grew up around Hyder and the coaching staff before ever donning a uniform. Now the athletic director at Kennesaw Mountain High School, he said the lessons learned from Hyder are applicable in the present day.

“He has meant more to me as I have grown up as an adult and parent and father and husband more than he did when I was in high school,” Baker said. “When you have a coach who cared so much, not having children of his own, he saw every one of us as his own. You always knew he cared about you, loved you. If you needed anything you could count on him to give you honest advice. He was always approachable and you genuinely felt he cared about you. What he taught is what we (former players) live by.”

As an A.D., Baker said he is implementing aspects of Hyder’s program into the Kennesaw Mountain system. He said Valdosta taught him the value of having a “cohesive leadership unit,” and the school is setting up a leadership council this year. The backbone of it? Hyder’s set of principles: God, family, academics, friends, Wildcats (or in this case, Mustangs).

Baker has written Hyder’s principles in his notebooks for 40 years and continues to do so today. He credits Hyder for turning he and his teammates into men. Hyder’s frequent hour-long speeches before practices didn’t resonate when Baker was 15, but he said he finds himself referencing them to this day.

“I attribute every success I’ve had in my life to lessons I learned on that field … I carry Valdosta with me everywhere and I’m proud to be associated with the program,” he added. “It was extremely special. Outside the birth of my children and marriage, that period was the best of my life; my fondest memories of life in general … I wouldn’t be where I am today if it wasn’t for Coach Hyder, Coach Tarpley, Coach Rudolph and especially my dad.”

Hyder died suddenly of a heart attack in 1996. A year later, he was inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame.

Just as Bazemore did, Hyder left behind a legacy far more valuable than winning. A legacy that has stayed with the city of Valdosta. He was able to live to his fullest and improve the lives of everyone he encountered. He used his football acumen for a greater purpose; a purpose living on through his players and coaches today.

The true embodiment of Hyder is in his own words: “Never, never, never quit.”